Homo naledi: How ancient hands and feet shed light on human evolution

Loading...

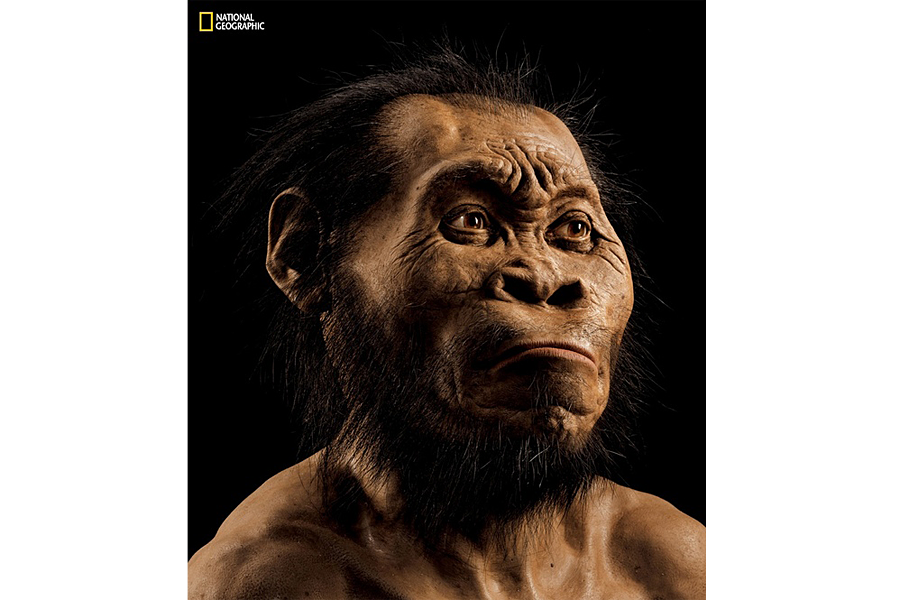

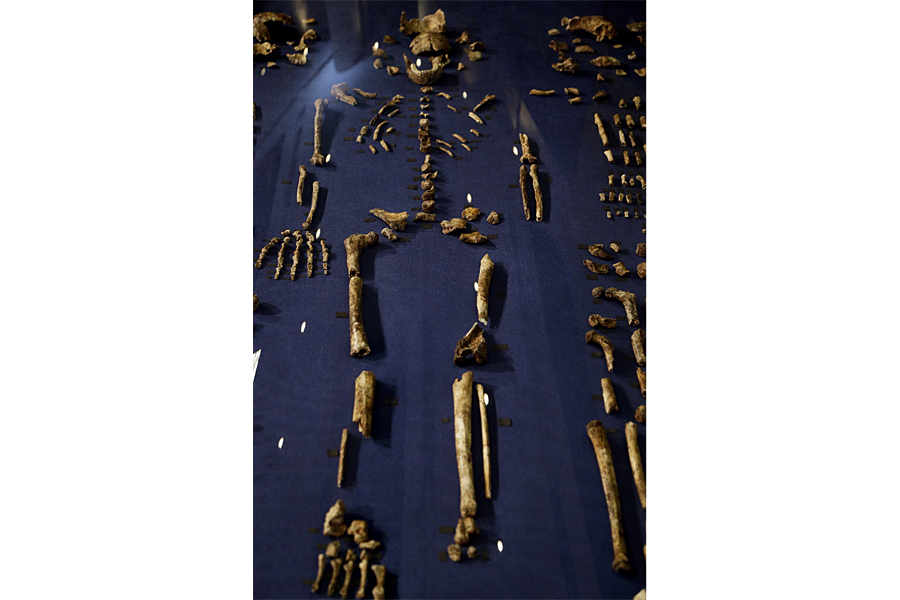

More details have trickled out this week from scientists studying the 1,550 fossil bones of Homo naledi, a newly discovered human relative unearthed in a South African cave. They provide more insight into how modern humans descended from the trees and evolved to walk upright, bearing tools in their hands.

In a pair of papers published online in Nature Communications this week, an international team of researchers studying the function of H. naledi’s hand and foot, based on hundreds of bones recovered in a cave in 2013, describe a mix of primitive and modern features not seen before among fossils from the human, or Homo, genus.

This week’s findings show that H. naledi’s hands and feet were well adapted for both modern functions, such as walking upright and using tools, and for primitive ones, such as climbing trees.

“It shows we have a much greater diversity in the fossils of human ancestors than we thought possible,” Tracy Kivell, a paleoanthropologist from the University of Kent who’s part of the team studying the bones, told the Guardian.

For example, in studying 15 hand bones, plus a nearly complete hand – a rarity in the fossil record – Dr. Kivell and her team found that the structure of H. naledi’s wrist and thumb is similar to ours and those of our extinct cousins, the Neanderthals. This indicates that the species would have had the dexterity to make and use tools, although no tools have been found.

But H. naledi also had longer finger bones than other hominins, an ideal feature for grasping limbs while climbing and suspending from trees.

“That combination was really quite surprising,” Dr. Kivell told the Guardian. “It shows you can have a hand that is quite specialized for manipulation and tool use in a species that is still using its hands for climbing, and moving around in the trees or on rocks.”

Its feet, based on 107 bones, are also similar to modern humans, formed for long-distance walking. But the toe bones are slightly curved, an indication that H. naledi could easily scale trees.

“It was unequivocally spending more time walking upright than not,” William Harcourt-Smith, a researcher from the City University of New York who’s studying H. naledi’s feet, told the Guardian.

“But you can imagine it spending time in the trees to gather fruit, or perhaps nesting in trees, or going there when there are predators around,” he added.

H. Naledi was first discovered by archaeologists working in a South African cave called Rising Star in 2013. The discovery of the the bones in the cave was the largest one in Africa, made possible by scientists who squeezed through a 7-1/2 inch wide crack and descended more than 400 feet to Dinaledi chamber. There, exceptionally preserved, were fossilized bones of 15 different men and women – from newborns to elders.

Researchers don’t yet know where H. naledi fits into our family tree, though they estimate the species to be 2.5 to 2.8 million years old, according to The Christian Science Monitor.

But until the bones can be dated, reports the Guardian, researchers won’t know whether H. naledi lived in isolation millions of years ago, overlapped with modern humans, or is a relative of a known human ancestor like Homo erectus.

"You can imagine this lineage emerging early on, close to the origins of the Homo genus, and hanging on for a long period of time,” Dr. Harcourt-Smith told the Guardian. “But that’s speculation. Evolution is messy. There is lots of experimentation going on, and lots of dead ends.”