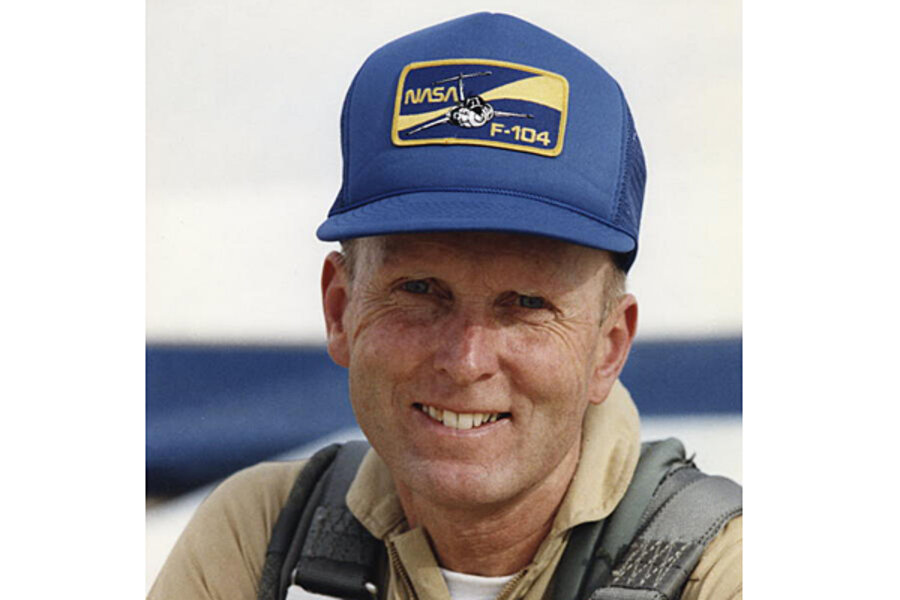

C. Gordon Fullerton, pioneering space shuttle pilot

Loading...

Col. C. Gordon Fullerton, a pioneering astronaut who was involved in NASA’s earliest ventures and in the success of its space shuttle program, died on Wednesday in Lancaster, California.

NASA announced his death in a statement.

Col. Fullerton, a member of the NASA astronaut class of 1969, was both an Air Force and a NASA test pilot, heading multiple test missions that made possible the space shuttle program. His credits in his nearly five-decade career include critically important test flights on the first space shuttle, the Enterprise, and 382 space-flight hours logged on two dangerous early space shuttle missions.

Fullerton, originally from Portland, Oregon, joined the US Air Force in 1958 after graduating with a Master of Science degree in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology that year. That was one year after the Soviet Union had begun sending unmanned satellites into space, one of which ferried upward a dog, and the same year that the United States put up into space its own first satellite, Explorer 1. Space flight, in other words, had just begun.

Fullerton was first trained as a B-47 bomber pilot at the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona. In 1964, he was selected to attend what was then called the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School (now the Air Force Test Pilot School) in California, and after graduation was assigned as a test pilot with the Bomber Operations Division in Ohio.

In 1969, Fullerton was selected for that year’s astronaut class. This was the same year as the Apollo 11 mission, which landed the first humans on the moon. Relocated to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Texas, Fullerton served on the support crews for the subsequent Apollo 14, 15, 16, and 17 lunar missions.

As the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union began to take on high-octane urgency, NASA began to pursue a new goal: the space shuttle program. This spacecraft, unlike the Apollo spacecraft that made parachute landings in the ocean, would be reusable. It would need to land like an airplane, gliding horizontally to a safe stop on a runway.

In 1977, Fullerton was assigned to one of the two flight crews to pilot the space shuttle prototype, the Enterprise. The shuttle, the world’s first, was made without engines and was not designed to go into orbit – space shuttle Columbia would complete that feat in April of 1981 – but to pioneer the mechanics of approach and landing. Throughout 1977, Fullerton and his compatriot piloted the experimental spacecraft in three unprecedented test missions over California as it was detached from the back of a Boeing 747 and allowed to glide back to Earth. Could it land? It could, Fullerton showed.

In 1982, Fullerton was assigned as the pilot on an eight-day orbital mission to expose the space shuttle Columbia to extreme thermal stress and test the shuttle’s other features, a task that a Christian Science Monitor article at the time called “the most demanding shuttle mission yet undertaken.”

At the time, Fullerton called the mission – his first visit to space, after some 24 years plying the skies – “the greatest (adventure) I ever expect to have in my life because just about everything about being on orbit is going to be a new experience.''

During that mission, from March 22 to 30, Fullerton was called upon to innovate an unexpected landing at White Sands, New Mexico, after the scheduled touch down point at Rogers Dry Lake was deemed, counter-intuitively, to be too wet, after heavy seasonal rains. The re-route caused the crew to remain in space for one day more than had been planned.

In July 1985, Fullerton was named the commander on a Challenger space flight carrying 13 scientific experiments. Just minutes after launch, the shuttle lost one of its three engines, a failure that required Fullerton, his crew, and flight control to off the cuff strategize a means to get the shuttle safely into orbit. The team succeeded, and landed that August in Dryden, California.

Fullerton left the astronaut corps in November 1986 to join the Flight Crew Branch at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center. There, he spent 22 years as a research test pilot and was involved in several major projects, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft program. He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in July 1988, bringing to a close a 30-year career with the military wing. He retired in 2007 as a NASA test pilot and from his post as Associate Director of Flight Operations.

Fullerton was inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2005, and the International Space Hall of Fame in 1982.