Curbing gun violence by ‘uncornering’ gangs

Loading...

Year after year, the politics of gun violence in the United States has been stuck on what seems to be one binary choice: more gun control versus more mental health care. Meanwhile mass shootings persist at a pace of more than one per day.

One American city is trying to avoid that trap.

In Syracuse, a city of 425,000 people in upstate New York, the homicide rate is three times the national average. “We’re ready to try something new,” proclaimed an editorial on Tuesday on the news site syracuse.com. The city is poised to launch a new gun violence prevention strategy that sees every citizen – including those committing violence – as agents of change.

“I don’t want to wait until a young man is behind bars to figure it out,” said pastor Lateef Johnson-Kinsey, director of a new office set up by the mayor last year to reduce gun violence, in a recent radio interview. “Your community must become your youth ministry.”

The city conducted a granular study of gun violence. It found that between 2012 and 2021, homicides rose yearly by an average of 26.5%. It sought input from community violence experts in other cities and used crime data to identify the sources of violence down to specific gang members.

The study helped officials understand that gang members believe violence is a salve for their hopelessness, a result of poverty and broken homes. It also helped them recognize why disparate violence prevention initiatives haven’t worked. Solving gun violence, Mayor Ben Walsh said in his State of the City Address in January, requires a coherent approach. It means fixing blight in neglected neighborhoods and caring for the mental health of police officers.

Syracuse’s strategy centers on two ideas that have proven effective elsewhere, in cities like Boston and Chicago. One is that gang members themselves are vital resources in social healing. The other is to think of redemption as a job. Officials have identified 50 “top brass” shooters in four gangs. Their goal is to enroll these “gentlemen,” as Mr. Johnson-Kinsey calls them, in a program that includes counseling, job training, and better schooling.

But with compassion comes expectations. By focusing on the instigators of gang violence, the city hopes to create new role models for their peers. It wants participants to see themselves as government employees whose job is equal parts individual reform and community renewal. The program includes a modest monthly stipend – or “scholarship,” as Mr. Johnson-Kinsey calls it.

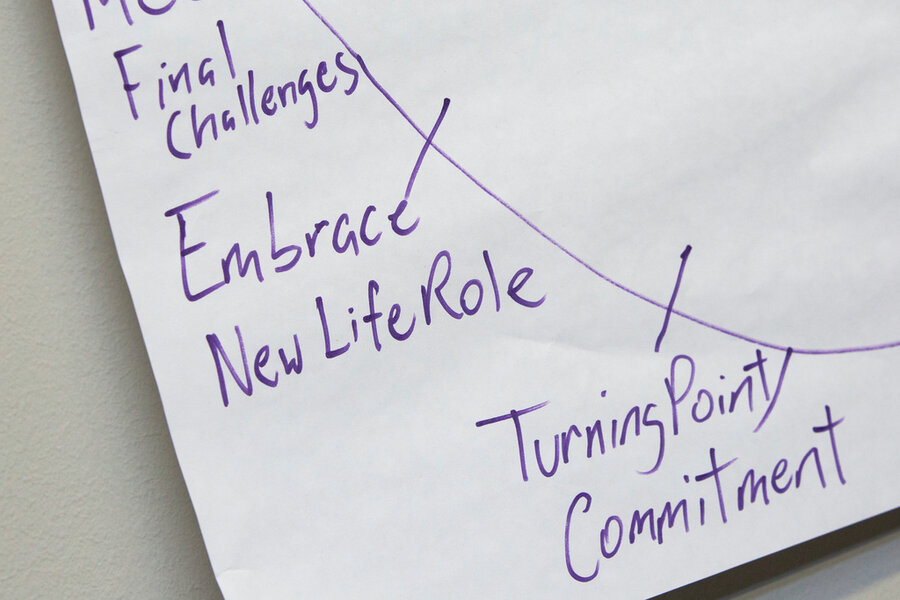

A similar program in Boston describes that approach as a process of being “uncornered” – a shift in mindset alike for individuals and communities caught up in gun violence. “Uncornered provides the scaffolding of resources that allow gang members to help themselves and those they love take advantage of new opportunities,” an article in Social Impact Review noted in February. It has “a more universal meaning. Most people would not think of a gang member as a solution, but rather as a problem. In this new way, we are all Uncornered in our thinking.”

Syracuse will need time to see if its plan’s many well-researched elements can work. For a nation caught in a debate about gun violence, the city is only the latest community charting a way out of the mental impasses of division and fear.