Next up as a region of peace: Asia

Loading...

Those who presume peace is possible for the world must often think in less than worldly ways. In the last quarter century, since the end of the cold war, regions of countries have strived to become “zones of peace.” The Americas and Africa have mostly avoided inter-state wars. Europe’s grand experiment to form a peaceful union has faltered with military intrusions in the Balkans and Ukraine. Plans are in the works to keep the Arctic free of conflict, as is the case for Antarctica.

But what of Asia, home to half of humanity?

Leaders in the region often speak of creating a region of peace. Chinese President Xi Jinping visits the United States this week in an attempt to find a peaceful accommodation for China’s rising military presence in a region largely defended by the US. And last week, Japan passed security legislation that reinterprets its postwar pacifist Constitution and enables its armed forces to better defend Japan and to cooperate with allies like the US.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe describes his military’s expansive new role as a necessary rebalancing of power in a region bristling with nuclear weapons, such as in North Korea, and aggressive claims to remote islands. “We must make the vast seas stretching from the Pacific to the Indian Oceans a zone of peace and freedom, where all adhere to the rule of law,” he said in a speech. “For this reason, too, it is our responsibility to fortify the US-Japan alliance.”

The president of the Philippines, Benigno Aquino III, has proposed that the South China Sea be designated a “Zone of Peace, Freedom, Friendship and Cooperation,” with countries de-militarizing the maritime areas and working together to exploit fisheries and offshore petroleum. Taiwan has made a similar proposal for the East China Sea. And attempts to form a regional free-trade zone, such as the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership, are often seen as peace promoting.

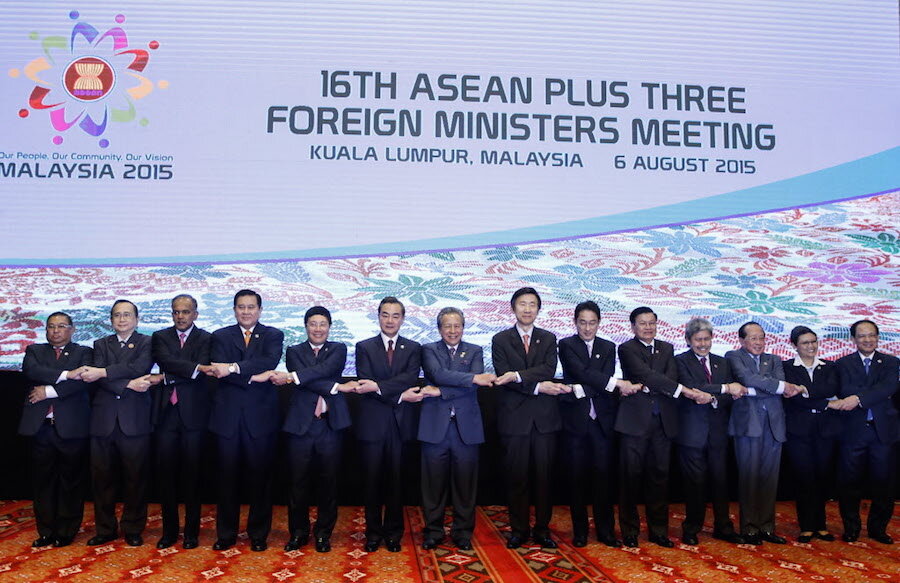

These cries for regional peace are getting louder as Asia perceives a weakening US role in the world and a stronger military presence by China. If Asia is to become a zone of peace, it need only look at its own sub-regional model. Since the 1970s, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has not only succeeded in curbing tensions among its members but uses its forums to invite other regional players to discuss differences and find ways to cooperate. Its annual East Asian Summit has become a focal point for finding common bonds.

ASEAN has succeeded by presuming peace should be the norm. Its 10 member states, stretching from Myanmar to the Philippines, have achieved an equilibrium by proclaiming shared values, a necessary way to cool nationalist passions. Its leaders are open about their intentions and listen to each other. If an outside big power tries to pressure a member of ASEAN, the others rally to keep the group’s cohesion.

With the giants of Asia now maneuvering their roles in the region, the time is ripe to further build on ASEAN’s success. A world at peace will need every region at peace.