Flint's housing crisis

Loading...

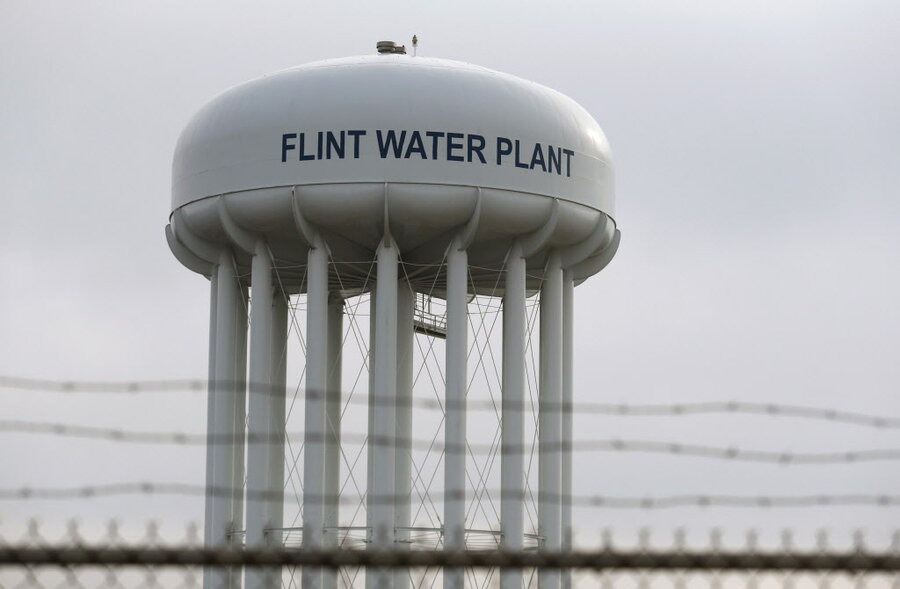

Flint, Mich. isn’t only troubled by bad water. A new study shows it also has one of the nation's most depressed housing markets.

An estimated 11,605 homes in Flint are vacant, according RealtyTrac’s report on nationwide housing vacancies for the first quarter of 2016. That’s 7.5 percent of the city’s total housing market, a vacancy rate nearly five times higher than the national average of 1.6 percent.

Flint leads the list for the most housing vacancies ahead of Detroit (5.3 percent); Youngstown, Ohio (4.4 percent); Beaumont, Texas (3.8 percent); and Atlantic City, N.J. (3.7 percent).

The data shows that the number of vacancies rises closest to Flint’s city center, where one in five houses are empty. THe problem extends to rental properties, 23 percent of which are standing vacant, compared to the national rate of 4.3 percent.

"It's a downward spiral as vacancy rates rise," RealtyTrac vice president Daren Blomquist told CNN. "A homeowner who is trying to sell their house might have to end up walking away, and that adds to the problem."

Vacancies were determined both from RealtyTrac’s own publicly recorded real estate data, which includes foreclosure and owner-occupancy status, and data from the US Postal Service that indicates whether or not a postal carrier has flagged a property as vacant. Metropolitan areas with at least 100,000 residential properties were included in the report.

Flint has had a difficult housing market for years. A 2000 Census brief on housing costs, released in 2003, noted that Flint had the lowest median housing value among large cities in the United States.

In 2015, things weren't much better. A 2WalletHub report done last year placed Flint dead last in an overall ranking of cities for the health of their real estate markets. WalletHub also ranked Flint as one of the cities with the highest number of homes with negative equity, and with the lowest median home-price appreciation. Its housing market ranked last compared to other cities of its size, such as Dayton, Ohio and Fall River, Mass.

While Flint’s housing market has had longstanding challenges, there is no denying that the water crisis is a recent contributing factor to its decline. In 2014, before the amount of lead in Flint’s water became a statewide nightmare, housing prices in Genesee County even appeared to be rising.

But that same year, Flint switched its water supply from Detroit to the Flint River, whose water supply was later found to be much more corrosive than the Detroit supply.

In August 2015, a group of Virginia Tech researchers investigated complaints by testing the water from homes in Flint. They determined that not only did water from the Flint River contain unsafe amounts of lead, but it would also cost the city millions of dollars to repair corroded and broken pipes. A public outcry followed the findings, and Flint residents later filed a lawsuit against the city of Flint and the state of Michigan, as well as other defendants.

Home prices slid by 8 percent in Flint in December 2015, the largest drop in the nation. It’s projected that the ongoing water crisis will push prices even lower.

"I would suspect there is not a lot of demand in buying or renting in the city at this point," Mr. Blomquist told CNN.