Why COVID-19 is likely to change globalization, not reverse it

Loading...

| Washington; Rome; Savannah, Ga.; Johannesburg; Berlin

In Italy, the economic toll of the coronavirus is visible in the sheer emptiness. It’s audible in the eerie quiet.

“It’s dead. There are no tourists,” says Gianni, owner of a small pizzeria in Rome. “I’m worried that I’m not going to be able to pay the rent.”

Why We Wrote This

Can the world’s fabric be undone? Some nationalists point to the coronavirus as a reason to seal borders and bring manufacturing home. But business experts say the benefits of trade are undiminished.

Due to a spike in cases, Italy is among the world’s hardest hit. On Monday night, the government banned public gatherings and asked people to stay home except for work or emergencies. Yet parallel challenges are emerging around the world: unfilled airplanes, half-vacant malls, and canceled public events and business conferences.

As stock markets totter, the emergency seems to be testing whether a wedded global economy will hold together. It comes as the idea of “globalization” has come under assault in the realms of public opinion, public policy, and even economics.

“This [epidemic] may end up as a great ‘teaching moment’ where we see that multilateral cooperation is essential,” says Richard Baldwin, an international economist in Geneva. “Or it may be seized upon by nationalists as an excuse to further restrict trade and immigration.”

The Spanish moss-draped oaks and brick-laid city squares of the American South’s low country are undoubtedly romantic. After all, some 8,000 weddings – lace-wrapped opening chapters of new lives – take place throughout the region every year.

But for many Americans looking to get hitched this year, it is starting to feel like someone dropped the wedding cake.

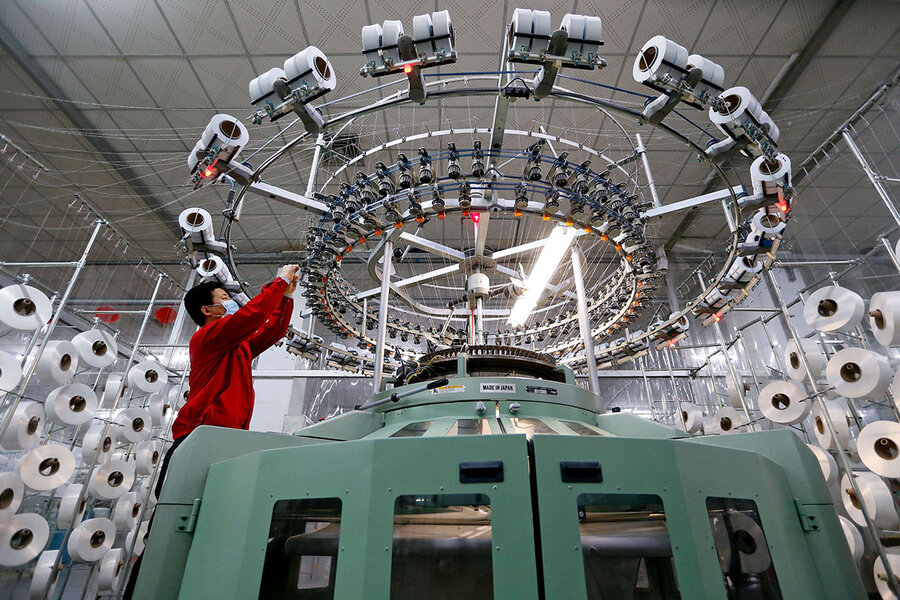

Heavily dependent on Chinese dressmakers who toil in well-lit factory floors from Wuhan and beyond, the $78 billion U.S. wedding industry is facing turmoil unlike any it’s ever seen. Waiting times for dresses have gone from six months to who knows when. Chinese suppliers have sent out apologetic but blunt notices that back orders could last for months.

Why We Wrote This

Can the world’s fabric be undone? Some nationalists point to the coronavirus as a reason to seal borders and bring manufacturing home. But business experts say the benefits of trade are undiminished.

The COVID-19 crisis comes at the absolute worst time: Late winter is when shopkeepers like Mia Mayer make nearly their entire year’s profit as nervous young women and their families waltz in and out of the changing booths.

“This is our world now,” says Ms. Mayer, who has sold over 1,000 dresses at her lacy boutique, That Dress, in Rincon, Georgia, since opening in 2012. “Wedding dresses, the decorations, the linen – all that stuff comes from China. The truth is, I never thought about this risk. You think about a decline in business, but that’s something that you can do something about. Now, there is no fix. There is no Plan B.”

The upheaval in the realm of weddings is just one example of a severe shock – a possibly transformative jolt – that is now rippling through an interconnected world economy.

And marriage ceremonies may be an apropos image to keep in mind. As stock markets totter – exchanges plunged around the world Monday, and NYSE trading was temporarily halted – the coronavirus emergency seems to be testing whether a “wedded” global economy will hold together or fall apart.

Globalization under fire

The test comes as the very idea of “globalization” – long vaunted as a path to shared prosperity for richer and poorer nations alike – has already come under assault in the realms of public opinion, public policy, and even economics.

Some nationalists in Europe and the U.S., already predisposed against unfettered trade, are now pointing to the virus as an added reason to seal the borders and bring factories back home.

The vast majority of business experts say the real lesson of the new coronavirus outbreak is, if anything, the very opposite. They don’t foresee any wholesale retreat from today’s web of far-flung commercial ties among nations, or benefits in doing so. Still, they expect the virus outbreak will alter the patterns of trade, perhaps in ways that have a local as well as a global character.

“Any reasonable board member would expect a CEO to be responding with greater supply redundancy and be prepared to pay for it,” says Mary Lovely, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “To the extent that this crisis appears to be heading toward a global phenomenon, it is a nudge toward a different, more diversified globalization rather than less globalization.”

Indeed, supply-chain specialist Rolf Zimmer in Germany says his clients are looking to make their supply networks more resilient, not more insular.

“This [epidemic] may end up as a great ‘teaching moment’ where we see that multilateral cooperation is essential,” says Richard Baldwin, an international economist at the Graduate Institute in Geneva.

“Or it may be seized upon by nationalists as an excuse to further restrict trade and immigration,” which would hurt nations that go that route, he writes via email.

Decline in poverty

Economists generally say that, while it’s true that trading relations come with risks, the benefits of economic connections tend to far outweigh the costs.

Decades of rising container-ship commerce and falling trade barriers, after all, have done much to drive a historic decline in poverty rates, most notably in Asia but spanning the world. In the process, median incomes in advanced nations like the U.S. have gone up, not down.

Yet the change has been uneven. Coupled with the trend of rising automation, globalization has created pockets of desperation when factories close. And, particularly in the new millennium with China’s full-tilt entry into global markets, the sheer pace of these changes has sown political upheaval. Donald Trump’s successful anti-establishment presidential run in 2016 and the British public’s vote to leave the European Union are, in part, signs of the social strain.

The coronavirus emergency is globalization’s latest test. Some world leaders say it’s vital for nations to meet the crisis by collaborating across boundaries on both health and economic matters.

“There is a common enemy, [and] we need to fight in unison,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, said in a recent public appearance.

For many workers and corporations, the economic side of that fight isn’t about lofty ideals. It’s about coping, here and now, with dents in both supply and demand.

In Italy, the economic toll of the coronavirus is visible in the sheer emptiness. It’s audible in the eerie quiet.

“It’s dead. There are no tourists,” says Gianni, owner of a small pizzeria in the center of Rome.

He has reduced the amount of pizza he makes each day, but he still can’t sell it all. “I’m worried that I’m not going to be able to pay the rent,” he says.

Due to a spike in cases, Italy is among the world’s hardest hit. On Monday night, the government took the extraordinary step of banning public gatherings throughout the country and asking people to stay home except for work or emergencies.

Yet parallel challenges are emerging around the world: unfilled airplanes, half-vacant malls, and canceled public events or business conferences.

Who supplies the suppliers?

Even far from the world’s biggest ports, in the tiny landlocked nation of Lesotho in southern Africa, the ripples are significant. In an industrial district of the low-slung capital, Maseru, some 40,000 people work in garment factories, churning out sweatshirts and skinny jeans for American brands like Levis, Walmart, and Costco. The industry is the nation’s largest private employer.

“Orders are already beginning to slow down,” says Bahlakoana Shaw Lebakae, founder of the United Textile Employees, a workers’ union.

Why? The textiles used by factories in Lesotho come from China. The logjams there mean that U.S. buyers are suddenly cautious purchasers.

“The textile industry here is already hanging by a thread,” Mr. Lebakae says, because it is reliant on a precarious American trade deal called the African Growth and Opportunities Act, which allows duty-free sales in U.S. markets.

Business leaders and officials worldwide are scrambling for solutions. But a videoconference isn’t always an adequate substitute for a business trip, which are harder to arrange these days. Finding alternative suppliers, whether of wedding dresses or microchips, isn’t easy.

Consider the closure of one parts factory in Codogno, Italy, an area affected by the outbreak. The shutdown is temporary, but it means that auto assembly plants across Europe, from Jaguar Land Rover and BMW to Renault and Peugeot, could be left short of crucial components.

“This coronavirus is a wake-up call. It’s, ‘Wow. We are much more vulnerable than we thought,’” says Mr. Zimmer in Germany, chief solutions officer at Riskmethods, which provides software to help companies manage supply chain risks.

It’s not that manufacturers haven’t thought about the need for resilience before. Many got a similar wake-up call in 2011 from an earthquake in Japan and floods in a Thai center of hard-drive production. But risks to supply networks may lie beneath the surface.

Even if a manufacturer has multiple suppliers, Mr. Zimmer cautions, what happens when those suppliers all rely on a single source for a key material?

Supply-chain experts say the worst of the China-related disruptions isn’t being felt in Western factories yet, due to the lag time of shipments arriving. The flow of global goods from pharmaceuticals to electronics hinges on two unknowns: How long will it take for Chinese factories to get back up to speed, and how many other producers around the world will face interruptions due to the virus?

“We’ve told companies to keep a lot of cash, and to make sure that you have a lot of stock of goods that are at high risk of stopping up,” says Christopher Parmo, chief operating officer of Verdane, a Europe-wide private equity firm that owns about 100 tech companies.

Deglobalization forces

Yet the outbreak could be more than just an alarm-bell to diversify supplier networks. It might contribute to a broader reshaping of the global economy.

On the one hand, it promises to accelerate “telemigration,” or the globalization of desk jobs that are becoming increasingly digital, argues Professor Baldwin, author of a 2018 book on the future of work. Already, the outbreak has prompted companies such as Twitter and JPMorgan Chase to ask thousands of employees to work from home. It’s not a long leap from such steps into a next phase of globalization, in the service sector.

Domestic telecommuting “is the thin edge of the wedge for international telecommuting,” he says.

On the other hand, if companies rethink their global footprints, several forces may nudge them to focus closer to home rather than further afield. The years since the 2008 financial crisis have already been marked by what some observers call deglobalization – a slowdown in the growth of trade and a rebound in protectionist measures such as tariffs worldwide.

“The virus adds to other reasons why firms are already rethinking their logistics,” writes Vicky Redwood of the forecasting firm Capital Economics, in a late-February report.

Beyond protectionist policies, those reasons include:

- Greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced when freight-transport distances are shortened.

- National security may be enhanced by moving important production homeward.

- It’s easier to customize products and respond to shifting consumer preferences when factories are close to the shoppers they serve.

- Rising automation is making labor costs a smaller factor in deciding whether to locate plants in high- or low-wage nations.

“Machines just repeat what they’re supposed to do, precisely,” says Harald Malmgren, a longtime presidential adviser and consultant to corporations on trade-related issues. “They work night and day. They don’t go on strike.”

Yet even if a trend toward more localized production accelerates, as Dr. Malmgren expects, it won’t happen overnight. And it doesn’t imply an incoming tide of jobs to nations like the U.S., if service-sector jobs simultaneously become more globally “traded” and automated.

The virtues of trade

And whether the overall arc of globalization bends upward or downward, the major economic takeaway may be for nations to avoid having “all eggs in one basket.”

“China isn’t the problem. Lack of diversification is the problem,” says Belinda Archibong, an assistant professor of economics at Barnard College in New York. In Africa, “lack of regional, intra-Africa trade is the problem.”

That’s a long-standing discussion within the continent. “Maybe this crisis is going to force us to trade more amongst ourselves,” says Blandina Kilama, an economist and senior researcher at Research on Poverty Alleviation, a Tanzanian think tank.

In the U.S., John Melin is an eyewitness to the virtues of trade. Brown & Haley, the candy company where he is president and chief operating officer, has seen a rising share of its Almond Roca sales coming from overseas.

China is a big source of that demand, which helps keep the firm’s 175 employees near Tacoma, Washington, employed. Mr. Melin and his team are working hard to keep the sales flowing and to pin down some alternative suppliers for packaging.

“Part of the health of our country and our high standard of living comes from the fact that people fly on Boeing airplanes around the world, and people buy iPhones around the world, and people admire the values and institutions of the United States,” he says. That integration with the world “brings more good than bad.”

In Germany, Yorck Otto similarly sees globalization as here to stay, and probably for the better.

“No, this wheel cannot be turned back,” says Dr. Otto, president of a business association representing small and medium-sized companies.

“The global supply chain will continue to get better and better every day. This globalization will be refined, and hopefully it will be also covered under new humanitarian laws and regulations so that the world can be a little bit better through globalization,” he says. “I’m not a great fan of kids sitting in Bolivia digging into soil to get materials to make batteries, for example.”

For now, back at the bridal shop, Ms. Mayer doesn’t know of too many alternative materials for the dresses she needs.

The supply predicament will likely push business toward do-it-yourself weddings, used wedding dresses on eBay, and a reevaluation of price points to consider American dressmakers, if they can keep up with demand.

“I’m sure [COVID-19] will get figured out in time,” says Ms. Mayer. “But in our world, time can make or break you. It’s scary. It’s your livelihood.”

This piece was reported by Patrik Jonsson in Savannah, Georgia; Nick Squires in Rome; Ryan Lenora Brown in Johannesburg; and Lenora Chu in Berlin. It was written by Mr. Trumbull.