Whither US entrepreneurs? Why a key engine of economic growth is sputtering.

Loading...

| Washington

Is the America of Benjamin Franklin and Steve Jobs fading out? That’s the provocative question raised by a troubling decline in the pace of entrepreneurship and new-business creation, which may be impeding job creation.

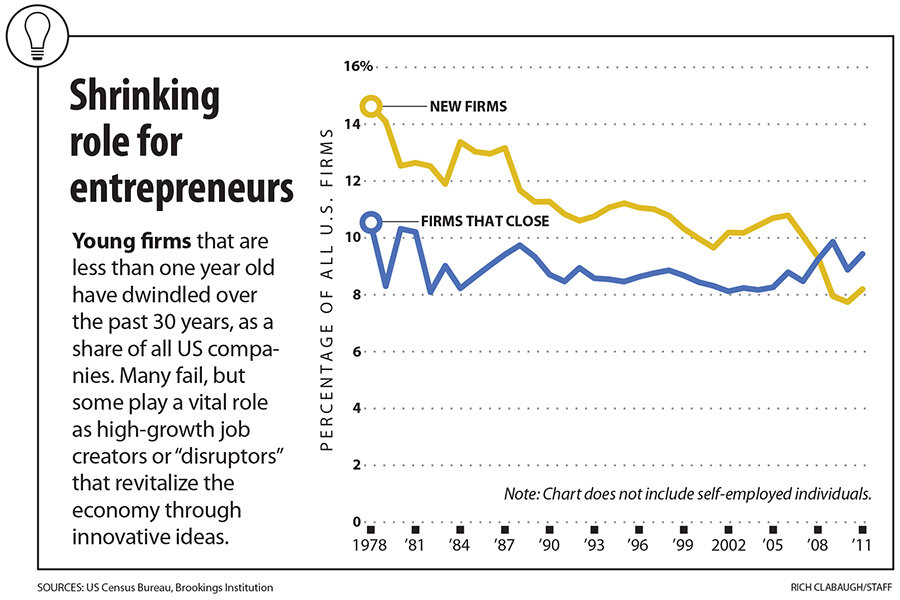

The pattern is clear in a new Brookings Institution report drawing on US Census data: Businesses less than a year old accounted for only about 8 percent of all US firms in 2011, down from nearly 15 percent in 1978.

So the era in which a company like Apple can go from garage to gargantuan in just a generation, it turns out, is also an era of erosion in what economists call “dynamism” in the economy – the churning process by which new businesses are formed, often fail, and sometimes succeed spectacularly.

What’s at stake is not just the story line that has woven itself into American culture from the days of Franklin to the Wright Brothers to the commercial rocketry of Elon Musk today. Recent research has also found a strong connection between business start-ups and job growth, so the sputtering engine of entrepreneurship raises worries the nation is shifting onto a slower-growth, lower-prosperity track.

The trend was in place even before the financial crisis of 2008, and it has taken root even though both major political parties pay considerable lip service to the goal of maintaining America’s entrepreneurial edge.

“If it persists, it implies a continuation of slow growth for the indefinite future,” warn economists Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan in the new report, published in May.

The “if it persists” part is key. No law written in stone says the trend of the past three decades has to continue.

America still has lots of entrepreneurs, from Silicon Valley to the plains of Texas. And the pace of new start-ups seems to have picked up at least a bit since 2010.

But economists who track the issue warn against an America-has-always-bounced-back complacency.

Consider some of the latest numbers:

•Both census and Labor Department tracking finds the number of newborn companies (less than a year old) has fallen in recent years even as the US working-age population has grown significantly. The Labor Department, for example, found 505,473 such firms in 2010, down from 634,276 in 2000.

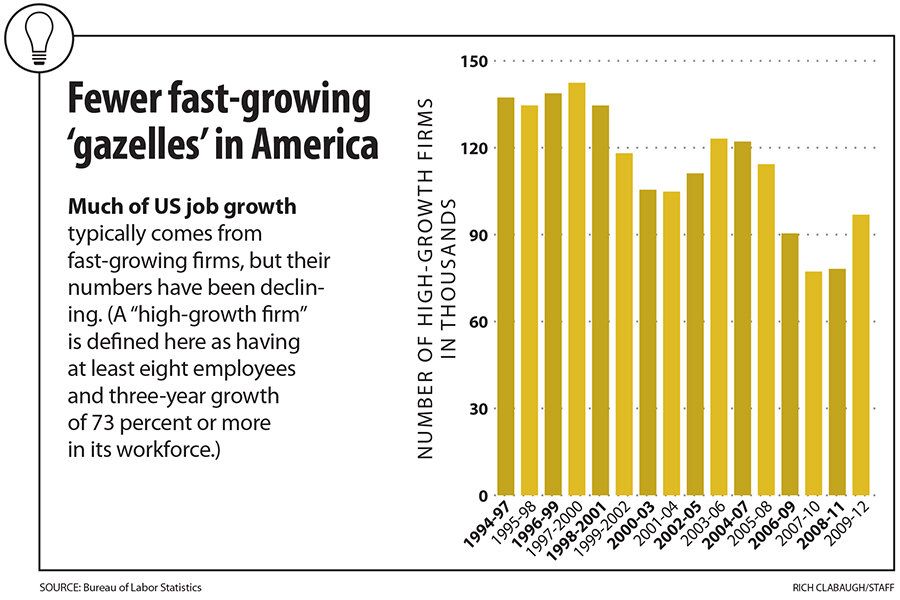

•The decline of young firms means a smaller pool of potential fast-growing companies – often called “gazelles” by economists. By one Labor Department definition, the US economy had only about 97,000 high-growth firms in the period from 2009 to 2012, down nearly 30 percent from the 1994-97 period.

•In that mid-1990s period, high-growth companies accounted for 3 percent of all firms and 7.4 million gross job gains. In the most recent period, the figures were 2 percent and 4.2 million.

“It’s rare to have a young business take off, but those that do add lots of jobs and contribute a lot to productivity growth,” John Haltiwanger, a leading economist in the field of business dynamics, said in a Federal Reserve magazine interview last year. “We have found that startups together with high-growth firms, which are disproportionately young, account for roughly 70 percent of overall job creation in the United States.”

Perhaps it’s no mere coincidence that gains in worker productivity have also slowed in recent years. Productivity is a gauge of how rapidly new ideas and technologies are spreading through the economy.

Plenty of innovation happens in large companies. But as Mr. Haltiwanger points out, start-ups tend to be vital players in this game.

What’s behind the decline in entrepreneurship?

Experts who study the issue say the drop remains somewhat of a mystery. Economists Mr. Hathaway and Mr. Litan say defining the causes is “an inherently tricky proposition.”

Here are some possible explanations:

Funding is harder to come by

Ken Wisnefski, founder of a successful Internet company, says the financing climate is very tight, for everything from venture capital and “angel” investments to bank loans.

“Business funding is probably going to have to come from your own means, or you’re going to have to engage friends and family,” warns Mr. Wisnefski, whose company WebiMax has been among New Jersey’s fastest growing since its founding in 2008.

Venture capital firms are providing a flow of capital that’s roughly the same now as before the recession, but those funds tend to go to a relative handful of high-tech or biotechnology launches. Internet-based avenues for “crowdfunding,” such as Kickstarter, are a welcome new source of funds but not an instant panacea for the challenge of financing.

Regulatory weeds get in the way

Deborah Sweeney, whose business MyCorporation near Los Angeles helps other small companies file papers of incorporation, says regulations are another big hurdle for potential start-ups.

“It is hard enough to get customers in the door,” she says in an e-mail interview. When one is also wrestling with confusing rules that can vary from state to state, it “can turn a would-be entrepreneur into someone who decides to just stay at a corporate job.

“Simplifying state laws and fees for incorporating or forming an LLC [limited liability company] would be a great first step” toward improving the start-up climate, says Ms. Sweeney.

Innovation is getting harder

Economist Tyler Cowen of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., has stirred interest with an argument that the economy is now in a “great stagnation” following a century or so of productivity gains from low-hanging fruit such as the rise of public schooling and electrification.

At a minimum, it’s possible the economy has hit a slow patch in innovation, as the momentum of the computer and Internet revolutions slows down. That would mean fewer ripe opportunities for new ventures by start-ups and older firms alike.

But Robert Atkinson, an economist who heads the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation in Washington, says the right policy climate could boost productivity growth back to about 2.5 percent a year.

Consolidation has gone too far

A wave of mergers, coupled with the growth of large firms such as Wal-Mart in retail and Bank of America in banking, has arguably made it harder for newly formed businesses to compete with entrenched players in their industry. Some business experts say lapses in antitrust enforcement weigh on entrepreneurs.

James Bosworth, chief executive officer of the new firm Back9Network, told a recent congressional hearing that the proposed merger of Comcast with Time Warner Cable appears to be significantly narrowing the odds that his package of golf lifestyle programming can find a viable home on US television screens.

“We had at least five productive, high-level meetings with Time Warner Cable executives in 2013,” Mr. Bosworth testified.

He said the Comcast deal has changed his optimistic outlook – apparently because Time Warner will soon share Comcast’s view of Bosworth’s network as competing with the Comcast-owned Golf Channel. (It’s still unclear if antitrust regulators will approve the Comcast merger with Time Warner.)

Business trends reflect demographics

To some extent, the aging of America may be visible in the pace of business formation. Historically, companies are most likely to be founded by people under age 50. Even if that changes a bit as baby boomers age (with start-ups by 60- or 70-year-olds becoming more common), it’s possible that aging trends are putting downward pressure on entrepreneurship.

The change is actually a good thing

Maybe large firms are getting better at playing the role of innovator, so fewer start-ups are needed than in the past. Or maybe would-be entrepreneurs are getting savvier, better at being selective about the opportunities they jump at.

“The benign view is, maybe it’s possible to get the same gains in productivity without all this churning of businesses and jobs. If so, that would be a good thing,” Haltiwanger told the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. “But if it was really nothing but good news, I ask, why aren’t we recovering more quickly? Why isn’t productivity surging?... We have been pretty sluggish at least since 2001.”

Symptom of larger problems

Last but not least in any list of possible causes, it’s important to note America has lots of economic challenges, and the decline in entrepreneurship may be a side effect as much as a problem in its own right.

Some examples: Global competition (including from countries striving to nurture entrepreneurs) has risen significantly. The rising inequality of incomes may mean that middle-class Americans have less money available to start businesses – and less optimism about their chances for success. The US patent system needs reform, many innovation experts say, to reduce unhealthy litigation.

Despite the challenge of reviving US dynamism, innovation, and job growth, it’s important to note that the economy is still generating entrepreneurial success stories.

Sweeney says Americans haven’t lost their traditional instincts for business opportunity. As the economy improves, she sees more clients getting excited about being masters of their own career destiny. The challenges are real, but she sees some sentiment “that things are headed in the right direction for business ownership.”

What could policymakers do to improve the climate?

E.J. Reedy, director of research at the entrepreneurship-focused Kauffman Foundation in Kansas City, Mo., says federal policy could do more to encourage innovation through tax credits for corporate research so that even firms with no taxable profits get help bringing their ideas to market. Immigration reforms also could welcome more foreign-born entrepreneurs.

More broadly, some economists say the need is to clear away barriers to business. The tax code could be simplified, not just to help US firms compete with global rivals but also to put young businesses more on equal footing with corporate titans.

Many economists also say Congress should resist cuts to investments – in things such as infrastructure and scientific research – in the name of budget discipline. The fiscal squeeze of rising entitlement costs won’t be solved by squelching the business climate, they argue.