How Muhammad Ali fought the law ... and won

Loading...

A year ago, veteran sports journalist Leigh Montville was more than halfway finished with his book about Muhammad Ali's epic but now-forgotten 1960s-era court battle. But he still didn't have a grabber of a beginning to start his tale.

Then Ali passed away, and the world erupted in mourning. "It was like Gandhi or Mother Teresa had died. There was this outpouring of love and great affection, which was deserved in the end," Montville says. "But it was far different in the time I'm writing about."

A half century ago, he recalls, "people didn't like him at all." If football player Colin Kaepernick bothered you with his refusal to stand for the national anthem at games, Montville says, "Ali was 10 times him in the abrasive qualities he had."

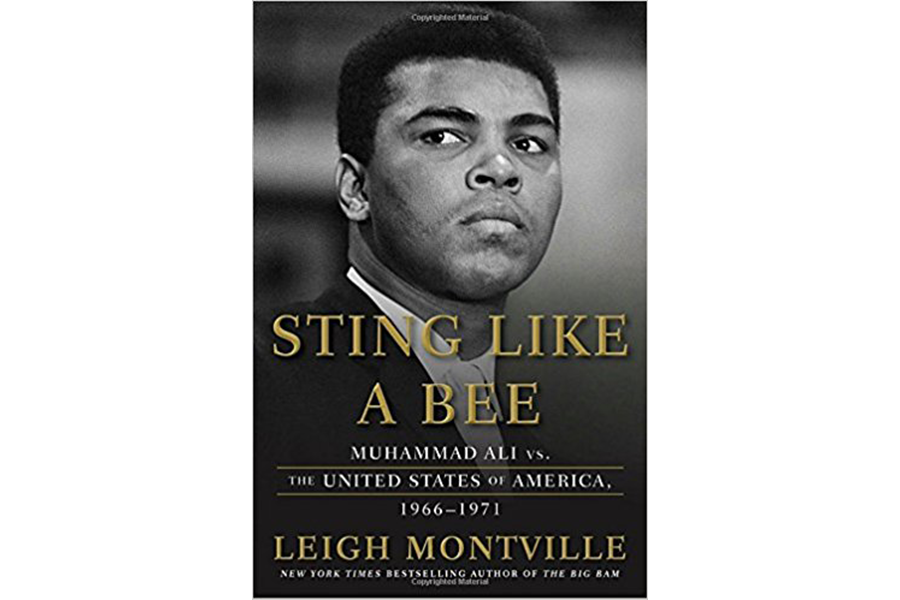

So Montville decided to lead his newly released book, "Sting Like a Bee: Muhammad Ali vs. the United States of America, 1966-1971," with the sharp contrast between then and now.

In an interview with the Monitor, Montville talked about Ali's faith, his legal fight, and what his draft battle means to us today.

Q: How did Ali become such an icon for the anti-draft movement during the Vietnam War?

At first, he flunked the written test that you need to pass, and he was married. So he was out of the draft in two different ways.

But then he got divorced because his wife wouldn't convert to the Nation of Islam, and they changed the rules so his test score qualified.

As soon as that changed, he was notified that he'd be reclassified to 1-A [meaning he could be drafted]. It was a definite statement being made by the government. I'm sure the way that he presented himself, speaking up and speaking out, was abrasive to the powers that be.

Q: Ali convinced a judge in Louisville, of all places, to allow him to avoid service as a conscientious objector. How did he manage to do that?

It was right toward the beginning of the whole process, the one time he could sit down and really speak from his heart. And there was no press involved.

He told his story, and the judge heard from his mom and dad and a member of the Nation of Islam. The judge, who was far from a big civil rights guy, thought for six weeks and then said Ali should be considered a conscious objector. But the Justice Department told the draft board this should be ignored, and it led to all sorts of appeals. Ultimately, he was sentenced to five years in prison, and he appealed all the way to the US Supreme Court twice.

Q: How genuine was his bid to avoid the draft?

It was real. He had become very religious, and throughout its existence, the Nation of Islam had resisted going into wars to fight for the United States. The head of the religion served 4 years in jail during World War II, and numerous other members had gone to jail because they wouldn't serve in the white man's army.

[Ali] wasn't part of the overall draft resistance. He was involved in maybe one or two demonstrations, and he wasn't a draft card burner or one of those people who went to the draft boards and poured cow's blood on the file cabinets. He was doing it all in a religious context.

Q: Was he courageous?

To Ali's credit, he could have joined the National Guard or just been an entertainer and a public relations guy for the military. He didn't have to go to Vietnam. They'd pretty much told them that.

But he was a young, impressionable guy and really went for it.

Q: His big mouth didn't help him one bit. How did he become so outspoken in the first place?

He'd come into the boxing world thinking it would be excited about him, but there wasn't a great deal of interest.

Then he ran across the wrestler Gorgeous George, who was packing them in. He would preen and say he was the greatest, the prettiest. Ali took all that in, the way you get people to come and watch by making them hate you.

Ali started saying his outrageous things about himself and his opponents, and he made himself into a wrestling villain before he became a villain for his religious and political views.

Q: How did he ultimately avoid going to prison?

The big things were the changes in the national perception of the Vietnam War and those who didn't want to go to war. And Ali had built himself into the cool, modern young black man. The Supreme Court let him go on a technicality.

It was probably his celebrity status got him involved in all of this stuff in the beginning, and his celebrity status that got him off in the end.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is immediate past president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.