‘The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store’ weaves a tale of love and community

Loading...

James McBride, one of today’s great American novelists, cares about his characters.

In a recent episode of “The New Yorker Radio Hour” podcast, the award-winning author professed that he’s not someone who “creates characters, and runs them up a tree, and throws cans at them.” It’s a spot-on assessment. Eschewing cheap shots, McBride favors a careful, winding excavation – reaching into history for the whys and wherefores of his novels’ crowded casts, while delivering whopper stories with electric finales.

And he’s done it again.

“The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store,” McBride’s triumphant novel that follows the widely acclaimed “Deacon King Kong,” serves up a riot of life crammed into a cacophonous corner of 1920s America – the Chicken Hill neighborhood of Pottstown, Pennsylvania. McBride works well in tight spaces. As he proved with the streets of south Brooklyn in “Deacon King Kong” and the life of James Brown in his 2016 biography “Kill ’Em and Leave,” constraint breeds depth. There’s a world of work, hurt, absurdity, and hope in Chicken Hill, offering McBride ample ways to ponder the appeal and elusiveness of the American dream.

The novel opens in 1972 when state troopers find a human skeleton at the bottom of a well linked to a long-gone synagogue. They question “the old Jew” who lives on-site and tag him as a suspect, miffed by his cryptic, defiant responses and curious why a mezuza, usually found mounted to a doorjamb, rested near the remains. The next day Hurricane Agnes strikes, and “God took the whole business – the water well, ... the skeleton, and every itty bitty thing they could’a used against them Jews – and washed it clear into the Manatawny Creek,” says the narrator. Justice, it’s clear, has been served.

So, what happened?

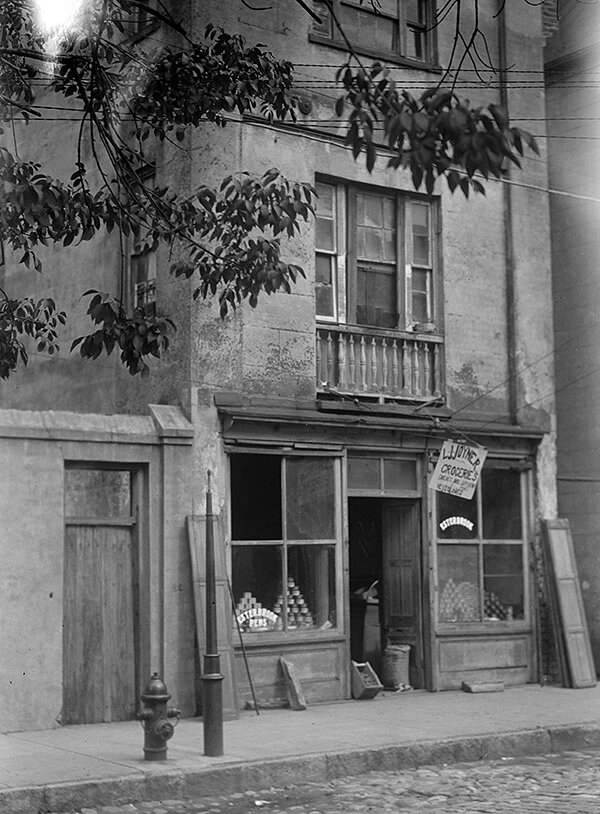

Rewind 47 years to the early days of Moshe Ludlow, the young Jewish manager of Pottstown’s All-American Dance Hall and Theater, an establishment serving the immigrant Jewish and Italian community, Black people, and white people. The entertainers range from klezmer greats to the Count Basie Orchestra. A snafu with the advertising for an upcoming show puts the fear of God and financial ruin into Moshe; in search of solace, he heads to Chicken Hill’s sole Jewish market, The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, where he meets the owner’s daughter, Chona.

A munificent beauty with a physical disability – one leg is shorter than the other following a childhood illness – Chona captures Moshe’s heart with her easygoing warmth. Four weeks later, they marry. To Moshe’s chagrin and the synagogue gossips’ delight, Chona continues to work at the store, providing a welcoming haven for her longtime Black customers, even as Jewish neighbors start leaving Chicken Hill.

They don’t go far. Heeding the siren call of the whiter, more affluent parts of town, the Chicken Hill Jews head 10 blocks downslope, despite the antisemitism that awaits. This urge to differentiate and define appears throughout the novel; so, too, do bias and bigotry.

The plot comes to a boil when a deadly attack at the grocery store leads to the lockup of an exuberant boy named Dodo, who is deaf. The denizens of Chicken Hill rally, all too aware that the mental institution where Dodo is wrongly imprisoned has a reputation for abuse and worse, particularly for anyone young, disabled, and Black. Be warned: Scenes in this section of the story, rife with menace, are intense.

McBride unfolds the efforts to rescue Dodo, plus side plots involving crackpot business schemes and sleazy bigwigs, with his trademark skill, brio, and frank talk.

The results are immersive, delightfully discursive – and thought-provoking. Whom, exactly, is the American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for? As made plain, the pervasive intolerance and discrimination of the 1920s and 1930s were dispiriting facts of life for a long list of individuals.

Even so, McBride insists, light shines in the gloom. By the end of the novel, a bit of evil has been squashed, just deserts have been served, and new community has been formed – all without the tossing of a single bruising can.