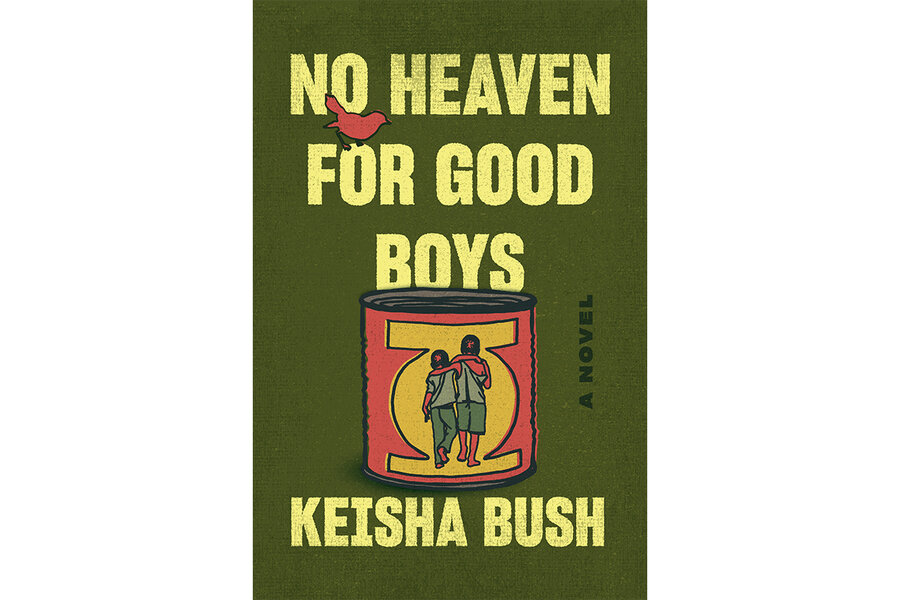

‘No Heaven for Good Boys’ tackles a family’s misplaced trust

Loading...

A ragtag band of boys run the streets in Dakar, Senegal. Most of them are not orphans – in fact, many come from loving families. Ibrahimah is one of those boys, longing for the comfort of his seaside village and the warmth of his mother’s arms. But life, for Ibrahimah and the other boys in the city, is far harsher than it should be.

Keisha Bush’s debut novel “No Heaven for Good Boys” whisks readers away to Senegal, where Bush spent four years living and working in the capital, Dakar. The novel follows Ibrahimah, a 6-year-old boy sent to study the Quran under the tutelage of a marabout, or a Quranic teacher. What follows is a heartbreaking story of loss, love, and family as he fights to stay alive.

The story is informed by the real-life experiences of thousands of children, known as talibés, who beg in the streets of Senegal. Families send their children to daaras, Quranic schools, thinking that their boys will receive an education and basic care under their marabouts. However, reports from the Human Rights Watch have unearthed troubling accounts of the lives of the talibés, who have to beg for money and food, and often don’t have access to clothing or healthcare. Many, according to the report, are physically abused and some also experience sexual abuse.

This is unfortunately the life waiting for the fictional Ibrahimah in “No Heaven for Good Boys.” Pressured by family and local religious customs, Ibrahimah’s mother and father, Idrissa and Maimouna, relinquish custody of their son to Marabout Ahmed, who quickly whisks the boy hours away from his village. There, Ibrahimah finds a small source of light in the camaraderie he builds with his older cousin, Étienne, who was also sent to Ahmed by his parents.

It’s impossible not to notice the dichotomy between the daily lives of Ibrahimah and Étienne, who have no shoes or clean water, and the privileged lives of the tourists and residents from whom the boys beg money. Bush also takes deft aim at religious hypocrisy, in which leaders hide their misdeeds under a cloak of piety, while the families’ desires to follow the tenets of their faith are manipulated to create cover for someone like Ahmed to continue his predations.

The most compelling character of the novel isn’t Ibrahimah – it’s his mother, Maimouna. While Ibrahimah’s story is most certainly at the center of the novel, it’s his mother’s determination to break with religious convention that pushes “No Heaven for Good Boys” forward. Haunted by her own childhood spent enslaved in her uncle’s home, Maimouna fights to reclaim her son from Marabout Ahmed, even though it could mean losing her family and home.

Bush is an adept storyteller; she spins out the colorful world of Dakar, and captures the sights and sounds of Ibrahimah’s home village, Saloulou, as well as the streets of the more industrialized Ouakam. You can nearly smell the ocean and hear the sizzle of meat over an open flame. But unfortunately, pleasant sights and smells aren’t the only things that are visceral in “No Heaven for Good Boys.”

While Bush is certainly a talented writer, there are certain parts of “No Heaven for Good Boys” that don’t quite fit together. The chapters – which switch between the points of view of Ibrahimah, Étienne, Maimouna, and even Ahmed – sometimes become disjointed. Bush does an excellent job of fleshing out Maimouna’s character, but Ibrahimah, despite being the focal point of the book, still reads as somewhat flat. Furthermore, there are many random American cultural references; though Bush justifies them with the plot, they still feel out of place in a story set half a world away from the United States. In the end, they act more as indicators of Bush’s American origins than as necessary additions to the story.

“No Heaven for Good Boys” is certainly not lighthearted. But despite the physical and emotional abuse in the novel, there is an immense sense of beauty and love in it as well. Bush’s writing and compelling storytelling will envelope you, until you realize you’ve spent hours lost in the streets of Dakar with Ibrahimah and Étienne. And by the end of it, you’ll find yourself wanting to do something, about Marabout Ahmed and others like him. Which is, undoubtedly, Bush’s goal.