Russians took their pianos with them into exile in Siberia

Loading...

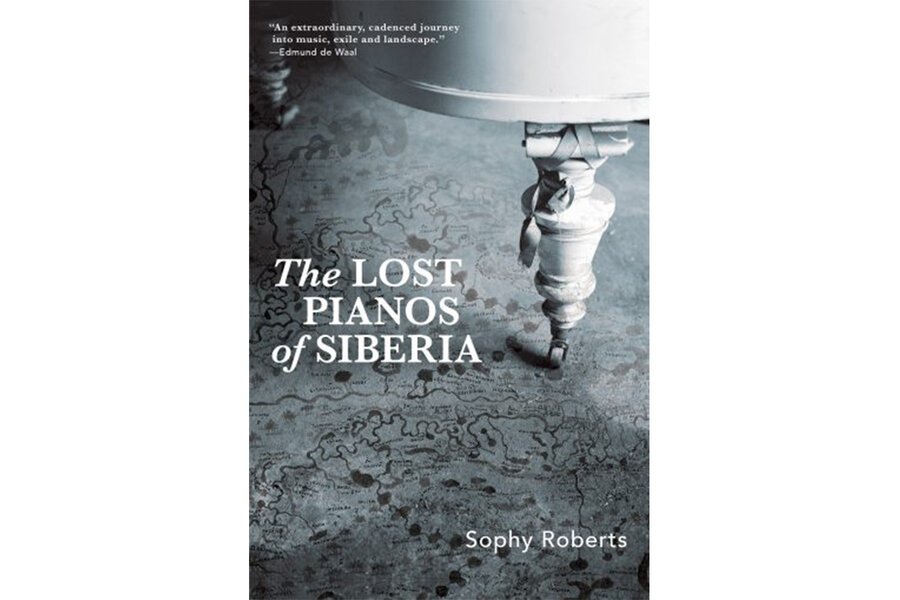

To say that Sophy Roberts’ “The Lost Pianos of Siberia” is among the unexpected works of history in recent memory is an understatement. Just ask the Russian state security official who, unable to fathom that the British travel writer had traveled to Siberia simply to search for pianos, kept pestering her interpreter. “His continued attention was unnerving, as if he didn’t believe I was in Siberia to look for piano stories,” Roberts writes.

Yet historic pianos and the stories behind them were exactly what Roberts was seeking over the course of her visits to the region. Her quest began as a kind of impromptu challenge: In 2015, after striking up a friendship with young Mongolian pianist Odgerel Sampilnorov, Roberts was encouraged by a mutual friend to find her a better instrument than her modern-day Yamaha.

“The more I listened to her play, the more I wondered how an historic piano would sound different in the steppe,” Roberts writes, but her search ultimately provided her with an excuse to immerse herself in an unfamiliar land. “I love nothing more than listening to people talk, whether in the pages of books, or across a table sharing a meal,” she writes. In detailing her efforts to ferret out the backstories of a succession of pianos, then, Roberts aimed to not only sketch a portrait of individual instruments but also of Siberia itself. “By following the pathway of an object,” Roberts writes, “I would get closer to understanding the place.”

Roberts documents the histories of notable instruments – among them a now-missing piano played by the exiled Romanov family after Bolsheviks overthrew the monarchy during the Russian Revolution in 1917.

Admitting that she perceives Siberia through Western eyes, Roberts taps into the seductive mystery the land holds for outsiders. “Siberia is far more significant than a place on the map: it is a feeling which sticks like a burr, a temperature, the sound of sleepy flakes falling on snowy pillows and the crunch of uneven footsteps coming from behind,” she writes.

Roberts peppers the narrative with a thousand concrete details. She succinctly charts the emergence of the piano as a favored instrument in Russia, crediting Catherine the Great – described as possessing “a collector’s habit for new technologies” – with contributing to its increasing popularity during her reign. Among Catherine’s possessions was an earlier iteration of the piano, a “piano anglais” specially ordered from London with a cabinet that Roberts likens to a Fabergé egg. By the mid-19th century, a Russian journal writer was quoted as saying: “You will find a piano, or some kind of a box with a keyboard, everywhere.”

But how did pianos find their way from the mainstream of Russian society to faraway outposts in Siberia, which, for centuries, has had a reputation as a land of exiles, prisoners, and frigid remoteness? It turns out that even cities intended for exiles need music. For example, the city of Tobolsk, owing to its status as “the main sorting house for Siberia’s incoming exiles,” acquired the emblems of “officialdom” – “governors, educators and their wives, and, inevitably, pianos.”

Roberts notes that the Soviet Union’s emphasis on music education led to pianos being churned out and distributed widely. “Tens of thousands of uprights were distributed into small towns, with piano factories even opening in Siberia,” she writes.

The hunt is often more satisfying than the discovery.

We learn that, during World War II, the Leningrad Philharmonic relocated to the safer environs of Novosibirsk, the “de facto capital of Siberia,” and toured surrounding towns. Roberts surmises that the Steinway grand piano that the orchestra used during the war just might still be housed in the Novosibirsk Conservatory. “The concert grand was too spectacular to have had any purpose other than to service the most important venue and musicians of the period,” Roberts writes, leading her on a fact-finding mission as interesting for its digressions as any conclusions.

The whole book is like that.

Writing energetically in the first person, Roberts roams freely from one tangent to another. She communicates her excitement at playing detective as well as her passion for bringing to life an unfamiliar place. And what of her initial mission to locate a worthy instrument for her pianist friend from Mongolia? Let’s just say that Roberts’ journey was worth it on that score, too.