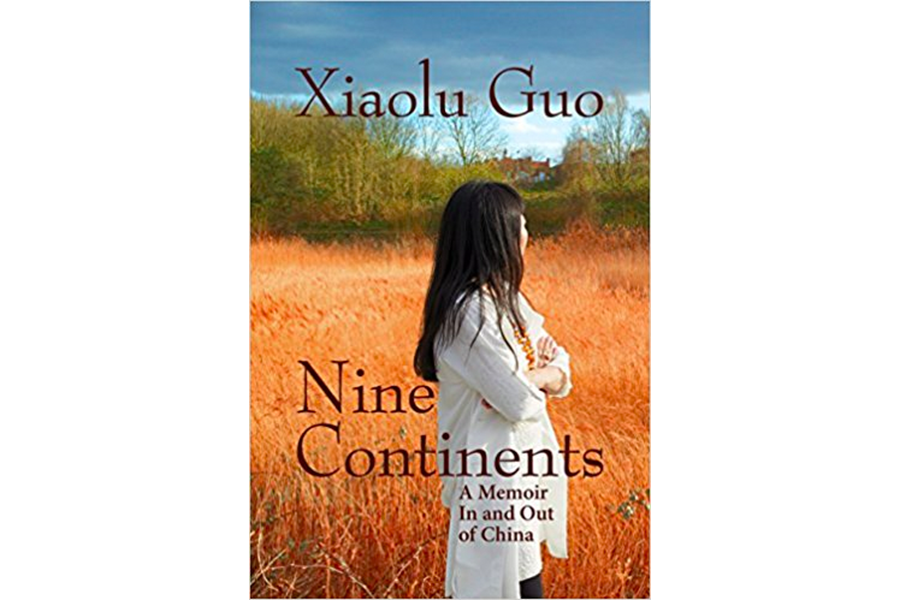

'Nine Continents' is Chinese author Xiaolu Guo’s resonant memoir about leaving her past

Loading...

Audiences familiar with Chinese-born, British-transplanted Xiaolu Guo’s prolific output know she’s alchemized elements of her own life to produce her fiction and films. Her remote village upbringing and Beijing education inspired “Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth” (2008 in English). The notebooks in which she recorded the many challenges to learning English became “A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers” (2007). The video footage from her elderly parents’ visit from China to London (and beyond) morphed into her film festival-lauded “We Went to Wonderland.”

Almost 20 years since she published her first novel in China, Guo lays bare her first 40 years in a single book, and for all her international success in print and celluloid, her life is a raw record of detachment, shame, and suffering. Originally titled “Once Upon A Time in the East,” which hit UK shelves last January, the US edition, Nine Continents: A Memoir In and Out of China, arrives this month as a testimony to resilience and hard-earned peace. Undoubtedly galvanized by the birth of her daughter at 40, Guo admits “the time had come to face the past.”

Divided into five major segments each representing a new dislocation – both geographically and emotionally – Guo prefaces each section with glimpses from the 16th-century Chinese classic, “Journey to the West,” about a monk’s pilgrimage from China to India to gather sacred Buddhist texts and return home. The monk's most notable companion is the powerful Monkey. Seemingly identifying herself with the simian immortal, Guo uses the interludes as both inspiration and respite from her onerous personal "journey to the west."

Born in 1973, Guo has been twice discarded. Her birthparents gave her to a childless couple who didn't have enough food. Guo’s ceaseless crying caused the couple to deliver her to her grandparents two years later because they “didn’t need a dying baby.”

Guo was raised in Shitang, a remote fishing village, by her grandmother, a hunchbacked woman with bound feet beaten almost daily by Guo’s “bitter, failed fisherman” grandfather. When Guo left Shitang at 7, she took two precious memories that fueled her adulthood: a monk’s promise that she was a “peasant warrior” who would “travel to the Nine Continents,” and the understanding she gained from a visiting art student that imagination had the power to “reshape a drab and colourless reality into a luminous world.”

From Shitang, Guo moves to more urban Wenling in 1980 to start school, cleaved from her grandmother, suddenly reclaimed by her parents and an older brother she never knew she had. Although her father offers some comfort – and shares his love of Western literature – Guo’s relationship with her mother and brother is unrelentingly contentious: “I was the insignificant flea unworthy of attention.” At 12, she’s sexually assaulted by her father’s co-worker for two years. “‘Stop crying! Every girl has to go through this!’” he screams as he rapes her; the words prove sickeningly true when Guo later learns all the girls in her university dormitory room survived similar violence.

Earning one of 11 admission spots amidst 7,100 test-taking applicants releases Guo to enter the renowned Beijing Film Academy; among her exclusive class is Jia Zhangke (of the Golden Lion-winning “Still Life”), leader of the so-called “Sixth Generation.” At almost 20, Guo gets her first pair of glasses and, with newfound clarity, she’s determined to “cut away the past and become someone else.” Freedom comes at a high cost, from severe isolation to a vicious boyfriend to fleeting relationships with foreign men.

In 2002, the elderly monk’s peripatetic predictions begin to come true when a Chevening Scholarship (“a British government award for future leaders from all over the world”) enables Guo to leave China for London. Navigating “in alien soil” means differences in language and culture repeatedly besiege her. And yet she prevails. Guo finally frees herself from her childhood, her family, and embraces “[her] own home now.”

Although undoubtedly Guo’s most resonant book to date, “Nine Continents” is not without literary flaws, from needless repetitions to bombastic declarations of “never” that don’t stick. Missteps aside, what remains is a viscerally affecting narrative in which Guo shares four decades of all the ways that being a woman – herself as daughter, sister, lover, and others as wife, mother, grandmother – has caused damage, humiliation, and tragedy.

But she has survived, even triumphed. Her own daughter – whose presence bookends Guo’s journey – is Guo’s self-admitted choice to “bring hope into the world by having a child and creating a person to whom I could give the best knowledge I had.”

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.