'Vasilisa the Beautiful' brings Russian fairy tales to life with gorgeous new illustrations

Loading...

There is no telling what storybook will spark a child’s imagination, lighting the path to a glittering realm of literature that they will long to enter again and again throughout their lives. In Midland, Michigan, the Christmas I turned six, an elegant friend of my Russian-professor parents – a white-haired, blue-eyed lady named Valentina Aleksandrovna (who made delicious poppy seed cake) – gave me just such a book. It was a collection of Russian fairy tales, illustrated in full color and bound in fir-green cloth, with gilded letters stamped on its cover that read: Vasilisa the Beautiful.

Inside I found 16 stories that captivated and bewildered me. The fairy tales I was used to, like “Sleeping Beauty” and “Cinderella,” featured helpless damsels and valiant princes; but the heroes of the Russian stories were different. Most of the girls were extremely clever, virtuous, and resourceful; most of the boys were spectacularly lazy, inept, and hapless. Yet, again and again, the forces of Slavic fantasy showered the boys with gifts and good luck – and the beautiful, brilliant girls became their wives.

The story “Emelya and the Pike” told of a boy, Emelya the Fool, who was so lazy that he lolled all day on the ledge of a warm, tiled stove – like a cat on a heating vent – refusing to bestir himself to help with chores. One day, after being wheedled to do an errand with the promise of presents, Emelya came upon a magic fish, a pike (a useful illustration depicted a slender fish with a kerchief tied around her head) who granted him all his wishes. To get what he wanted, Emelya had only to say, “By the will of the Pike, do as I like!” Hearing of the miraculous fish, the Tsar (a “tsar” is like a king, my parents explained – and the hissing way they pronounced the combination of the two letters “TS” fascinated me) sent an officer to Emelya’s cabin and ordered him to come to the Tsar’s palace. Unwilling to leave his warm perch, Emelya ordered the stove to unroot itself and to zoom off to the palace like a giant sled, knocking down everyone who stood in its path. Soon, lazy Emelya married the Tsar’s daughter, the lovely Tsaritsa (like a princess) Marya, and became Tsar himself.

In another story that stayed with me, “Sister Alyonushka and Brother Ivanushka,” the prudent Alyonushka could not keep her impulsive little brother, Ivanushka, from quenching his thirst by drinking water that had pooled in the hoofprint left by a baby goat. “May I drink out of the hoof?” the brother plaintively asks her. “No, little brother. If you do, you will turn into a kid,” she tells him. Drinking it anyway, he promptly turns into a goat. (Eventually, Alyonushka saves the day, and her brother regains human form.)

But the standout figure among these tales was the title character, Vasilisa the Beautiful. Like Cinderella, she lived with a cruel stepmother and wicked stepsisters; unlike Cinderella, she had no fairy godmother to help her but only a magical doll – a gift from her mother’s deathbed. Assisted by this doll, Vasilisa faces down the fearsome witch Baba Yaga, who lives in a hut that stands on chicken’s legs, surrounded by a terrifying wall of human bones topped with glowing skulls.

Can you imagine Cinderella confronting such a horror? I was thrilled: children adore the hair-raising shiver of the supernatural sublime. Needless to say, in the end, Vasilisa outwits Baba Yaga, vanquishes her mean step-relatives, and marries a Tsar. And just as needless to say, Vasilisa is indeed beautiful as well as brave – her beauty so extraordinary that “it could not be pictured and could not be told.” Nevertheless, a demure drawing of Vasilisa appears in the book, portraying her in an orange and gold sarafan and a sky-blue headscarf, giving an inkling of her charm.

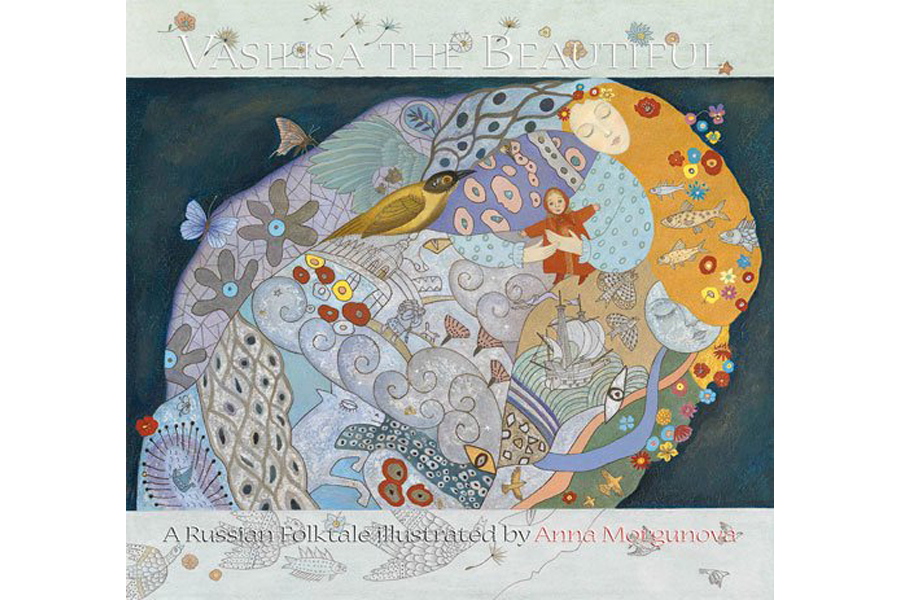

In recent years, I have hunted down ancient hardcover copies of this memorable book (edited by Irina Zheleznova, who translated many of the chapters) to give to my godchildren, to my nephews and niece, and to other children I know. But they are scarce (though a paperback version still exists.) I was elated this fall to discover that a brand-new, hardcover version of Vasilisa the Beautiful – the crowning tale of the collection I love – has been published, in a fine translation by Anthea Bell, gorgeously illustrated by Anna Morgunova with full-page panels that burst with tomato reds, piney greens, cobalt and cerulean blues, gold and saffron. Morgunova’s collagist compositions recall Klimt and Chagall; and she enriches their backdrops with floral and animal elements (wildflowers and berries, wide-eyed fish, rabbits with fangs, prancing horses).

Vasilisa, serene and golden-haired, floats dreamlike among them. I have noticed that Anthea Bell’s translation is slightly less bloodcurdling than Irina Zheleznova’s; in the older version, the witch Baba Yaga continually assigns Vasilisa challenging tasks, under the threat, “If you don’t I shall eat you up.” In the newer version, Baba Yaga merely warns that if Vasilisa fails to come through, “It will be the worse for you.” This, I suspect, may make bedtime after storytelling a little smoother.

Sometimes, when reading aloud to the children in my life, hoping to hit upon the story that will unlock the charm of reading for them, I give it a little too much effort. For instance, one ink-dark summer night in a cabin at a northern lake, I terrified my little niece and a close friend’s child by reading “Hansel and Gretel” to them by lantern light, intoning the words: “Nibble, nibble, little mouse; who’s that nibbling at my house?” in a far-too-convincing witch voice.

But it also delighted them. These archetypal, enchanting, foreboding tales lodge in the childish mind, endure and resonate. They hold the key to real-life dangers, hopes, and emotions that the child will confront with recognition in later years when she grows up – unfair bosses, near-impossible assignments, envy, even treachery. As they grapple with these tests they think: Ah, yes ... how is it that this seems familiar? Why do I seem to remember this unusual predicament?

Though most fairy tales illustrate the perversity of luck, the Russian fairy tales I know bring unusual relish and realism to showcasing the petty failings that undermine human dealings – not just outright wickedness but carelessness, cowardice, forgetfulness, and indiscipline. This makes them singularly valuable in helping a person reckon with a variety of vicissitudes. Sometimes, we learn as adults, sloth, not virtue, is not rewarded; sometimes, good people undergo horrible trials. But there still can be a happy ending.

I am hoping that this new edition of "Vasilisa the Beautiful" will serve for the children in my life (and for any other child who discovers it) as a gateway tale that lures them into the borderless lands of fiction. The English-language stories we learn in the nursery begin: “Once upon a time....” The Russian stories more often begin: “Zhili byli” – “There lived, and were.... ” That phrase awakens the thought: “There still live, and still are...” – and that the fantastical and the realistic coexist, in literature and in life.