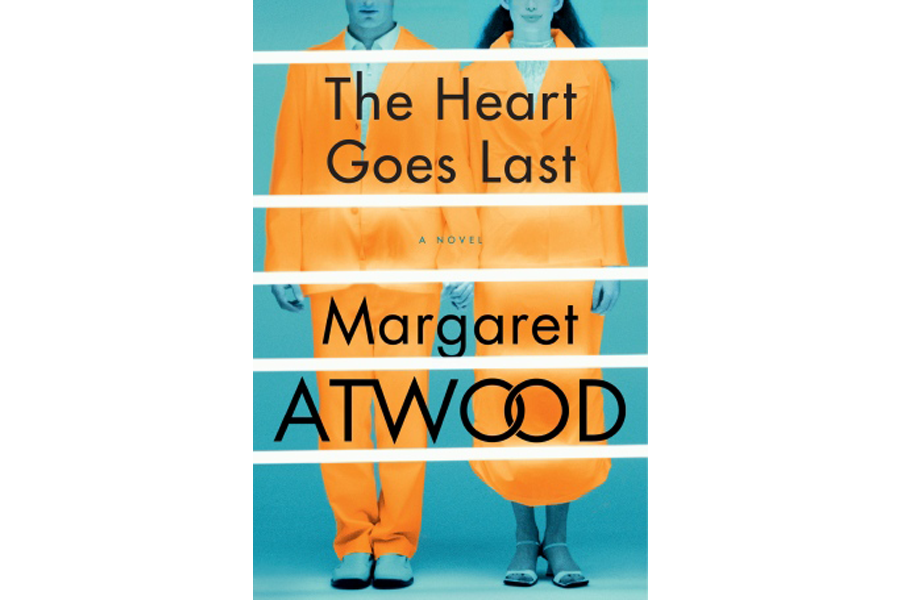

'The Heart Goes Last' offers a struggling young couple a Faustian bargain

Loading...

Stan and Charmaine, the lead characters in Margaret Atwood's 15th novel, The Heart Goes Last, live in what could be described as a mild dystopia. There's been some sort of severe economic crash; public works are battered and run-down, and violent gangs roam the streets after dark, looking for easy looting. Gas still pumps at gas stations, power stations still generate electricity, roads still connect distant cities, cell phone towers still emit their signals, and the lights of Las Vegas still shine, but there are constant oblique references to a recent social collapse that's left what used to be normal life a bit adrift in bleak savagery.

In this desperate, hopeless world, Stan and Charmaine are struggling to get by. She has a job at a sleazy bar/bordello, and they live in their car, worried all night long about marauding gangs, wondering how long they can go on. At work, Charmaine even winces at daytime sitcoms “that aren't funny and anyway comedy is so cold and heartless, it makes fun of people's sadness.”

A ray of hope offers itself: in the town of Consilience, the Positron Project runs a social engineering exercise where selected participants spend every other month in clean, ideal homes with well-paying jobs and fellow Positron participants as neighbors. The catch: on the alternate months, those participants become jump-suited prisoners in Positron's prison – monitored, taking prison jobs, while strangers live in their house for the month.

For Stan and Charmaine – she's an idiot, and he's a venal, self-pitying idiot – the positives of the arrangement far outweigh the negatives, and they decide to try it, even though Stan's bad-seed brother Conor tries to warn him off the idea. The couple make their way to Consilience (“the bus trip goes on for hours, in a steady drizzle,” we're told, “through open countryside, past strip malls with plywood over most of the windows, derelict burger joints. Only the gas stations appear functional”), a town where “the surface ambience is like a Doris Day film.” Stan and Charmaine rationalize their choice by contending that the Positron arrangement is just a clarification of the trends of their society anyway: “Citizens were always a bit like inmates and inmates were always a bit like citizens,” they tell themselves, “so Consilience and Positron have only made it official.”

Things go well at first, but Atwood complicates her plot lines by having Charmaine fall in love with the man who lives in her house while she's in prison, something Positron strictly forbids. A convoluted connection of events leads to Stan's apparent death and subsequent assumption of a new identity, “Waldo,” working in Positron's division making “a Dutch-designed line of exact-replica female sex aids … for home and export” while smarmy Consilience grief counselors try to help Charmaine get on with her life.

World-building, the keystone of the science fiction genre in which Atwood so regularly dabbles, is by any measure exceedingly weak in "The Heart Goes Last." Grinding universal poverty doesn't seem to pose an obstacle to Conor traveling those same hours and hours in order to show up at Consilience, for instance, nor does it seem to be hurting the international exact-replica female sex aid market. The Positron Project seems to operate as a law unto itself, but the law itself – and the government that presumably still imports oil and sends around garbage trucks and keeps a national electricity grid operating – is conveniently and inexplicably missing. The novel regularly gives the impression of being a cobbled-together thing.

No doubt this is partly because it was cobbled together. Atwood originally posted segments of the Positron story in 2012 and 2013 for the website Byliner and has here assembled and continued those original chapters. But the skill to mold a coherent novel out of periodical installments was a Victorian speciality that has faded almost out of existence today, and Atwood and her editors certainly aren't doing much to revive it; almost every part of "The Heart Goes Last" feels opportunistically and sometimes sloppily contrived.

And the defects extend even to the level of language, where Atwood usually satisfies: we learn that “getting into the Positron Project won't be a slam dunk,” for example, and about Conor we're told “his Off switch never worked too well.” At one point we're told “Charmaine is basking like a seal. Or a like a whale. Or like a hippo. Like something that basks, anyway.”

These and dozens of other banalities combine with the novel's lazy pop culture references (you just know that Stan's new name was chosen solely so we could be given a "Where's Waldo" reference, and sure enough, we're given one) and phoned-in raunchiness to produce one of the weakest Atwood novels in years. The hypothetical at the center of the book – in tough economic times, would you sacrifice your freedom for security? – is treated so shoddily and whimsically that it dissipates almost completely, leaving only morons and sexbots.