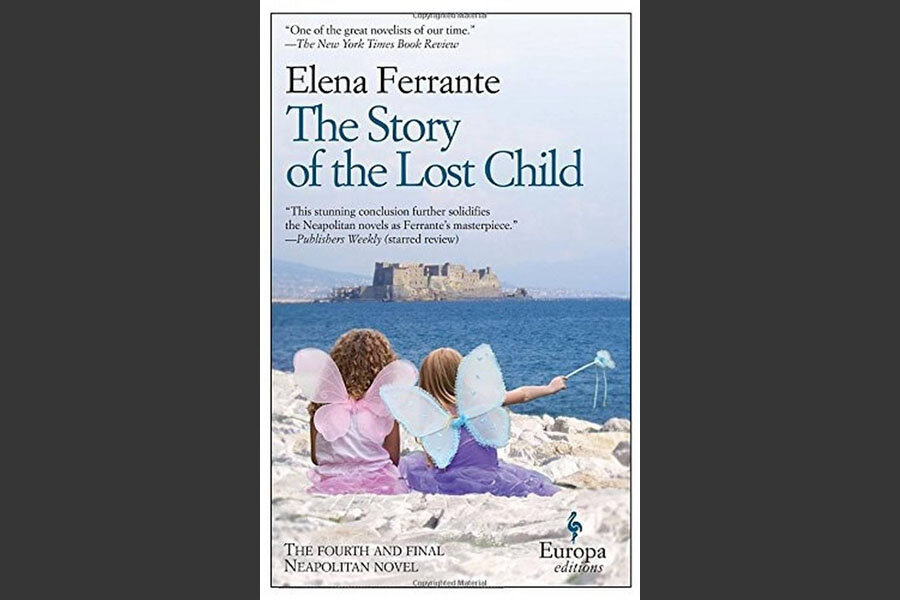

'The Story of the Lost Child' brings Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet to an extraordinary close

Loading...

The narrator of the four novels that comprise the Italian novelist Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet is, like her creator, an Italian novelist. The fictional novelist is Elena Greco, a writer whose impoverished childhood in Naples bleeds into the pages of her fiction. In the final novel of the series, The Story of the Lost Child, the narrator worries that one of her most successful books is in fact a failure, precisely because it does not reflect the actual feel of life.

Perhaps, she thinks, it “really was bad, and this was because it was well organized, because it was written with obsessive care, because I hadn’t been able to imitate the disjointed, unaesthetic, illogical, shapeless banality of things.”

This may sound like Ferrante using a fictional doppelgänger to sketch out her own novelistic aesthetic, one that rejects the artifices of pristine formalism in the name of a disorderly verisimilitude. Elsewhere, however, the narrator insists that it would be very naïve to see the author behind every statement in her books; she is, after all, a novelist, a maker of fictions. As such, her impulses are not purely confessional.

Early in the novel, Greco writes: “it’s more and more difficult to keep the thread of the story taut within the chaos of the years, of events large and small, of moods.” This comment is essentially a defense of the same “obsessive care” criticized in the first remark. Here she embraces the necessary exclusions and artful shaping that differentiate fiction from an indiscriminate documentary chronicle.

A large part of Ferrante’s genius is her capacity to show that the conflict her narrator articulates is a false dilemma: It’s possible to imitate the “shapeless banality of things” within the confines of a taut, propulsive story. This is exactly what she does with surpassing skill in both her new novel and the earlier books in the Neapolitan series. The result is a powerful and provocative kind of fiction – a story that nibbles at the edges of its own shape as a story.

The third novel ends with Elena on the brink of an affair that will destroy her marriage to an influential professor in Florence. She’s roughly 30 years old, a published author, a mother of two young girls, and a social success in the cultured spheres of Florentine society that are so different from the violent streets of Naples where she grew up. Her life, in short, could not be more different than that of her best friend, Lila, who functions in all the novels as a kind of shadow protagonist, a constant if often inverted reflection of Elena. Lila has not left Naples. In fact she hasn’t left the old neighborhood, where she remains embroiled in local feuds and dramas.

The fourth novel is ablaze with dramatic incidents. There’s adultery, suicide, political terrorism, more adultery, shocking betrayals, and a mysterious disappearance. There’s also, however, what the narrator simply calls life, “in all the most dispiriting aspects of dailiness.” Kids get colds, spouses squabble, people converse just to pass the time. The alchemy of Ferrante’s art is to interleaf the mundane and the dramatic.

This juxtaposition is only one of a series of paired oppositions that give the book thematic coherence and intellectual tension. There’s the formal Italian of Florence and the raw dialect of Naples, street smarts and book smarts, violence and restraint, domestic and public life, the demands of motherhood and the necessities of professional life. The most fundamental pairing, the nucleus that other themes and characters orbit, is Elena and Lila; their “splendid and shadowy” friendship is an abiding source of mystery, pleasure, and anguish.

Many of these tensions are ultimately unresolvable. Early in the novel, Elena feels “how restrictive, at 32, being a wife and mother might be.” When she moves suddenly and dizzyingly into a different sort of life, she is briefly fulfilled. But the feeling is illusory; her daughters are “left in the margins.”

Her success as a novelist allows her to live a satisfying and independent intellectual life, but it causes resentment among family and friends back in Naples. “‘Go think about your books,’” Elena’s little sister tells her, “‘life is something else.’” This sister, says her mother, is the one who has actually achieved something: a lasting marriage. “‘What you think you are means nothing to normal people,’” her mother says. “‘She didn’t study, she didn’t even graduate from middle school, but she’s a lady.’” Elena’s novels have won prizes and been translated into many languages, but she’s divorced.

Lila has focused her formidable intellect on creating a flourishing computer company in Naples, but a sense of thwarted artistic vocation glimmers beneath all her restless activities. While Elena is a novelist who maneuvers imagined characters, Lila is a novelist of the actual, manipulating real people and situations in her Naples neighborhood to create various intricate plots and subplots. She even has a novelist’s talent of suggesting hidden depths; she can “orchestrate situations in which she let you perceive that under the facts there was something else.”

Both Lila and Elena – whose nickname, Lenu, echoes Lila’s name – struggle to give shape and order to the world. But Lila experiences strange recurring episodes in which the boundaries of people and objects appear to dissolve and disintegrate; Lenu, in a different way, also experiences a radical instability in others and herself. After discovering a disturbing secret about a lover, she wonders if he was just a stranger that she was forcing “to assume a clear and definite character.” She feels in herself a latent, violent shadow self that threatens to emerge.

This all leads to a certain skepticism about the project of a novelist. When words delineate characters with stable and knowable outlines, they falsify the liquid blur of life. In a period of despair, Lila mocks Elena’s efforts to write, implying that as a novelist her friend imposes an order and meaning on the world that it fundamentally lacks: “‘Where is it written that lives should have a meaning? Is the meaning that line of black markings that look like insect shit?’”

Elena does not abandon faith in the act of writing, but she too feels a certain melancholy doubt about the ability of stories to contain the relentless flux of things. Near the end of the final novel in this moving and extraordinary quartet, she offers this harsh insight: “Unlike stories, real life, when it has passed, inclines toward obscurity, not clarity.” This turn toward obscurity and irresolution is balanced by a temporal broadening of the narrative into the long centuries of Naples’ history. If not exactly consolation, this at least offers a sense of continuity. Fascinated by the city’s past, Lila discovers that behind every stone, arch, and monument of Naples lies a “permanent stream of splendors and miseries.” Such an enduring stream of human splendors and miseries is precisely what Ferrante’s four Neapolitan novels reveal and preserve.