'Let Me Be Frank with You' returns to Richard Ford's best known protagonist

Loading...

While many retirees turn to crossword puzzles and word games to keep their minds sharp, Frank Bascombe is deleting words from his vocabulary.

“In recent weeks, I’ve begun compiling a personal inventory of words that, in my opinion, should no longer be usable – in speech, or any form,” he says in the opening of Let Me Be Frank With You. (This, it must be noted, is a truly awful title – and one that would be banned in China under its no puns rule.) “A reserve of fewer, better words could help, I think, by setting an example for clearer thinking.”

Among the verboten are: “no problem,” “reach out,” “hydrate,” and “I am here for you.”

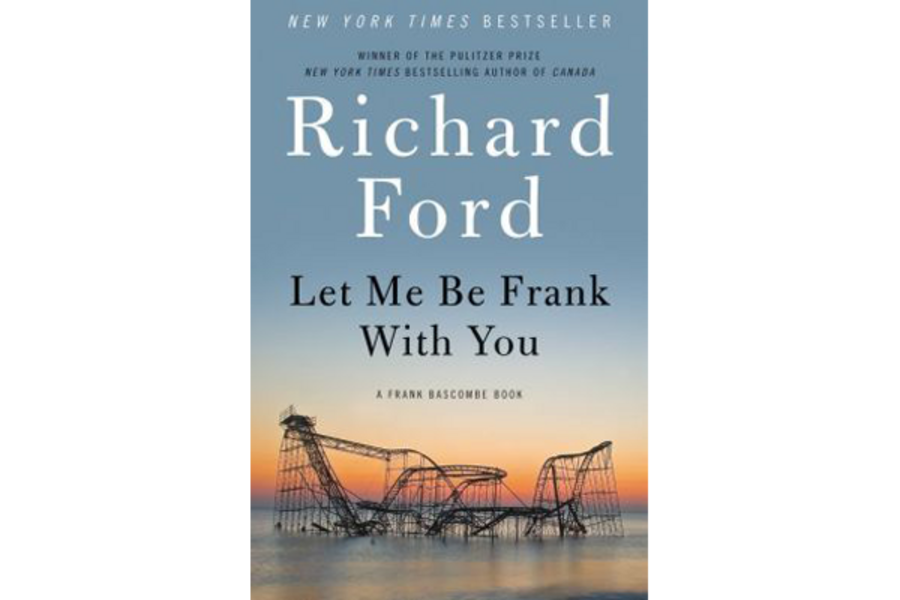

Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Ford, who took a historical road trip in 2012’s excellent “Canada,” returns to New Jersey and his best-known character in four interlinked novellas set in the wake of superstorm Sandy. Frank remains an everyman, with trenchant and often hilarious observations on everything from aging to race in America. Both he and his beloved coastline are feeling battered and rather the worse for wear, especially in the first novella, “I’m Here.”

After 2006’s “The Lay of the Land,” Ford had said that he was finished with Frank, who he chronicled over three novels beginning with 1986’s “The Sportswriter.” “Let Me Be Frank With You” serves as a coda to the trilogy – a rueful book that believes in clear language and taking the time to be kind.

“Love isn’t a thing, after all, but an endless series of single acts,” Frank says.

He is now retired – “a member of the clean-desk demographic,” as he puts it – living in Haddam with his second wife and using his time to do good works, mostly at a safe remove. While Frank is in his late 60s, he actually sounds a decade or more older. (Worrying about falls was something my grandparents did in their 80s, for example.)

Frank meets soldiers returning from overseas every week and reads to the blind. His current choice? V.S. Naipul. He no longer looks in the mirror. (“It’s cheaper than surgery.”) And he eschews social media. (“I’m not on Facebook, of course. Though both my wives are.”)

For those who haven’t read the previous books, Frank sums up his life for a visitor: “I’d gone to Michigan, have two children, an ex-wife and a current one, that I’d sold real estate here and at the Shore for 20 years, once wrote a book, served in an undistinguished fashion in the Marines and was born in Mississippi….”

He lets the visitor tour the house where he and his wife live, listening to the story of what happened to her when she grew up there and managing not to immediately pack his bags and move anywhere else. Listening to others is what Frank does in these novellas, bearing witness to others’ pain, whether from tragedy or illness.

In the third novella, “The New Normal,” he brings a therapeutic foam pillow to his ex-wife, who has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s and has an apartment in an upscale assisted-living community that “looks like a model home in the AARP journal.” It gives him a chance to ruminate again on their failed marriage after the death of their son, Ralph.

In the first, he visits his former seaside dream home, which was destroyed by superstorm Sandy, to view the destruction with the man who bought it. And in “The Deaths of Others,” after trying to put it off, he visits a dying former friend from “The Sportswriter” era whom he hasn’t seen in decades.

“Like most people, of course, I was never a very good friend in the first place – mostly just an occasionally adequate acquaintance,” Frank thinks, although after the conversation, “occasionally adequate” appears to be a higher bar than some can attain.

The first novella takes its title from a story Frank's second wife Sally tells him about Sioux warriors in the 19th century, who all shouted, “I’m here,” as they were about to be executed. And in the novellas, Frank both affirms his own presence and, whether it’s by shaking the hand of a returning soldier or offering a pillow for comfort, acknowledging others.

“In my view,” Frank says, “we have only what we did yesterday, what we do today and what we might still do. Plus, whatever we think about all of that.”