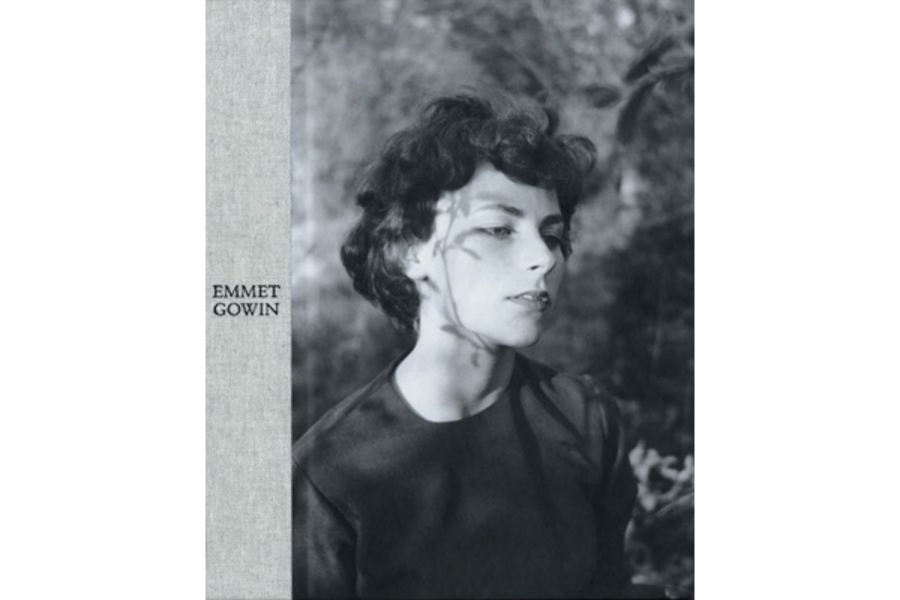

Emmet Gowin

Loading...

Emmet Gowin once quipped that if he had never married Edith Morris, we probably wouldn’t be considering his work today. She remains the creative font from which his inspiration flows.

In Emmet Gowin, a retrospective from 1967 to the present, we come to know and appreciate the retired Princeton University professor’s singular vision. What began as an intimate love story between two people broadens to embrace the natural world. Yet, the intimacy of his family portraits never diminishes.

In "Edith, Chincoteague Island, Virginia, 1967" we see the back of her head, hair loosely gathered in a barrette, a slightly worn and stretched sweater draping her shoulders which are pulled back. The focus is shallow, her cheekbone well defined against the soft focus of the water that captures her gaze. Highlights on her skin glow, while every shadow harbors some receding detail revealed on close inspection. Even from the back we can see that Edith is serious, in every way his collaborator.

As Gowin turns his gaze to the aftermath of the Mount St. Helen’s volcano explosions in the ‘80s, his spiritual underpinnings become more overt and the visual poetry that began with Edith deepens. He writes, “Even when the landscape is profoundly disfigured or brutalized, it is always deeply animated from within.... This is the gift of a landscape photograph: that the heart finds a place to stand.”

When Gowin records aerial photos of the Nevada nuclear test sites and other ravaged landscapes around the globe, his expert use of 19th-century printing processes keeps the tones of the moonlike surfaces warm and inviting. The viewer has a heartfelt place to stand.

In 2001 Gowin returns to the minutiae of daily life – this time moths in a forest near the border of Panama and Colombia. And there among his personal items is a silhouette tracing of Edith which he places in the moth collecting sheet lit from behind. “I was in her presence and she in mine....” he writes. Appropriately he has returned to his muse, a moth to the flame.