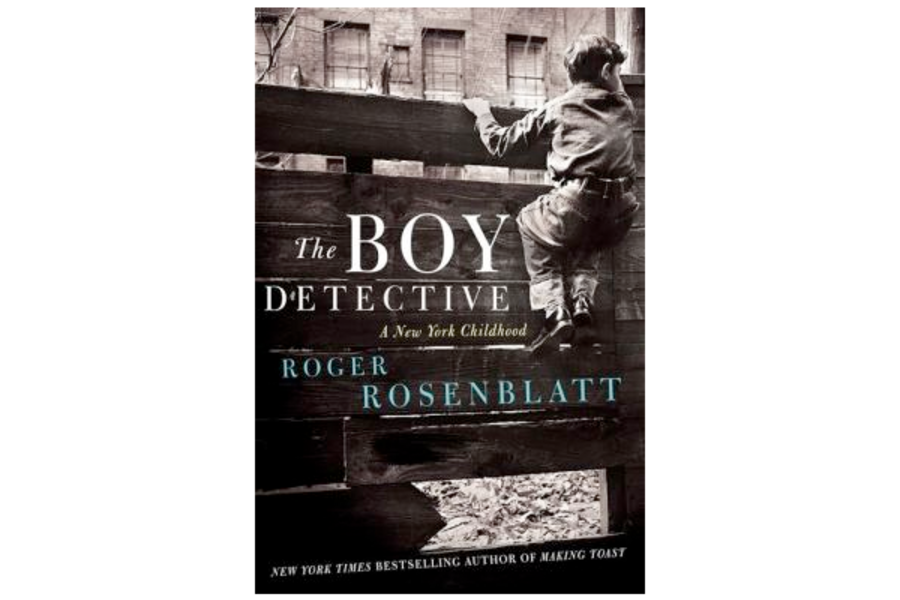

The Boy Detective

Loading...

In his newest book, Roger Rosenblatt tells his story walking.

The journalist, teacher and author of 16 books, including the bestselling memoirs “Making Toast” and “Kayak Morning,” takes a nighttime stroll through the streets where he grew up in New York.

"A man retraces the steps of his youth in order to determine where he has been and where he is. Your basic mystery story. Mixed motives, false leads, dead-end trails. Innocence. Missing persons. Bodies everywhere," writes Rosenblatt.

Written in the spirit of E.B. White’s “Here is New York” and Alfred Kazin’s “A Walker in the City,” the book is a meandering ramble through Rosenblatt’s past and the streets of New York's Gramercy Park neighborhood. Some readers will find that delightful. Those who prefer to walk with a destination firmly in mind are likely to find their patience tested. (If you find his recollection of the time he willed himself to dream he was an owl detective an amusing piece of whimsy – “As a largish owl, I had some difficulty stuffing my feathers in to the taxi” – you’ll be fine.)

"I believe in spare writing. Precise and restrained writing. I like short sentences. Fragmented sentences, sometimes," Rosenblatt wrote in “Unless It Moves the Human Heart,” his bestselling account of a semester in his class on Writing Everything at Stony Brook University. He still likes the fragmented sentences, but no one would accuse “The Boy Detective” of excessive restraint. It’s an extended riff, more meditation than memoir.

“I tend toward creative drift myself. Just like Penelope, I lose my thread,” Rosenblatt confides.

As a nine-year-old, Rosenblatt fancied himself a detective-in-training. “I wanted to be Holmes, himself,” he writes. “The detective I concocted for myself was not exactly like him. What I imagined was a composite made up of Holmes’s powers of observation, Hercule Poirot’s powers of deduction, Sam Spade’s straight talk, Miss Marple’s stick-to-itiveness, and Philip Marlowe’s courage and sense of honor — he who traveled the ‘mean streets,’ like mine, and was ‘neither tarnished nor afraid.’ The fact that, as far as I could tell, I lacked every single one of these qualities, and saw no prospect of ever achieving them, presented no discouragement.”

His youthful reconnaissance missions helped him develop an eye for observation that the journalist and writer later put to good use, winning two George Polk Awards, a Peabody and an Emmy.

On his walk, Rosenblatt writes that he is still accompanied by that boy, lonely and imaginative, who dreamed of having a young Teddy Roosevelt for a partner in crime.

“I am the spitting image of myself,” he writes. “How like myself I am. This is why I do not believe in time. How could I if I feel the presence of the boy as completely as I do the man, in many ways more completely since the boy is more completely realized. He who existed in me over half a century ago walks with me today.”

While not as moving as “Making Toast,” his widely acclaimed memoir of the first year after his daughter’s death at the age of 38, when he and his wife took in their grieving grandchildren and son-in-law, “The Boy Detective” offers glimpses of Rosenblatt’s childhood. These are mixed in with discussions of Roosevelt, Dashiell Hammett, Edgar Allan Poe, Edith Wharton, and other famous writers and residents of Gramercy Park, peeks at those walking the streets with him and reminiscences of how those streets have changed, and his thoughts on other New York landmarks. (“Its feeling of calm comfort is what appealed to King Kong, I am sure of it,” he says of the Empire State building.)

Rosenblatt’s parents expected him to behave like a miniature adult. (Similar pressure apparently was not put on his much-younger brother, whom his mom doted on.)

"Roger," his dad told him, "that's no way for a twelve-year-old boy to behave."

"Dad," he said, "I'm eight."

Rosenblatt writes about his home, with the walls hung with William Randolph Hearst’s excess paintings, which his parents purchased from Gimbel’s. “The canvases cracked like stale cake.”

But those glimpses will be tantalizingly few for those expecting a straightforward memoir of childhood. Rosenblatt, who refers to an unseen companion as “Pal,” also mixes in fake confessions, such as Poe, who invented the detective story, admitting to the “Murder of Marie Roget.” (There’s also a tone-deaf one about Hitler.) Rosenblatt muses on the Road Hill House murders, which shocked Victorian England and inspired Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens. For those who have read Kate Summerscale’s excellent “The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher,” there’s nothing new here.

Rosenblatt, who has taught for more than 40 years, also talks to his writing students during his perambulations.

“[Y]our memoir is not about you. So, stay out of it,” he tells them. “At the outset of a memoir, you are propelled by the desire to let the world know who you are. Soon you will discover that you don’t really care that much about who you are, and that writing with that goal alone will turn boring, cloying. You will tire of yourself just as you tire of others who think only of themselves....”

Readers who believe a journey is worth more than the destination will find a kindred spirit in Rosenblatt, who is generous company during his wanderings.

“My favorite part of being a detective is just this – the walk, just taking in the world.”

Yvonne Zipp is the Monitor fiction critic.