Why Camille Dungy can’t separate her garden from Black history

Loading...

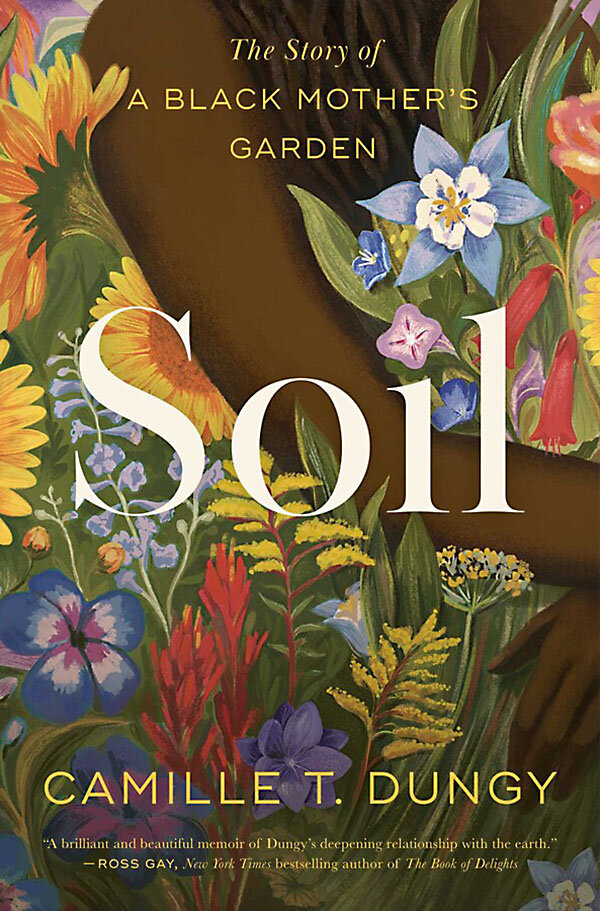

Camille Dungy’s latest book, “Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden,” began as a study of the plants, animals, and insects in her garden.

Then the nation erupted.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWhen writing about her garden, author Camille Dungy couldn’t ignore how her ancestral roots as a Black woman were deeply tied to the soil.

“I was doing the bulk of my writing in 2020,” Ms. Dungy recalls, “when my daughter was home and I was responsible for overseeing her remote schooling. ... [and] an awakening or reckoning with social injustice and disparities occurred.”

“It became impossible for me not to weave all these events together,” she says.

On the one hand, “Soil” offers useful gardening tips, such as how deep to plant alliums. But along the way, readers learn about history, Black culture, and parenting, too.

Ms. Dungy acknowledges the toil of America’s Black citizens and honors their unquenchable thirst to “grow their own beauty” in what was a very parched land. Scattered throughout “Soil” are time-tested words of wisdom to support the flourishing of plants and to inspire those willing to dig into their own roots to uncover the resilience in their ancestry.

“I can’t understand who I am right now and who my daughter can be,” Ms. Dungy says, “if I can’t fully understand who my family has been and what experiences they ... passed along to me.”

In her book “Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden,” Camille Dungy creates a plot of pages enriched by their diverse mixture of nature, nurture, history, and memoir. On the one hand, “Soil” offers useful gardening tips, such as how deep to plant crocuses and alliums. But along the way, readers discover that tumbleweed was transported from Europe, black-eyed peas arrived aboard slave ships, and both gardens and children need patience and grace.

The recipient of the 2021 Academy of American Poets Fellowship and a 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship, Ms. Dungy unearths American history, one that recognizes the toil of America’s Black citizens and honors their unquenchable thirst to “grow their own beauty” in what was a very parched land. Scattered throughout “Soil” are time-tested words of wisdom intended to support the flourishing of native and imported plants as well as inspire those willing to dig into their ancestral roots to uncover the resilience from whence they come.

Ms. Dungy, a University Distinguished Professor at Colorado State University, recently spoke with the Monitor. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWhen writing about her garden, author Camille Dungy couldn’t ignore how her ancestral roots as a Black woman were deeply tied to the soil.

How did this idea get started, the telling of American history by sharing stories about gardening, the lives of African Americans – including your own ancestors – and your experiences as a mother?

“Soil” began as a simple environmental study of the plants, animals, and insects that were in my garden. I was working to create a space of welcome, ... a space in my yard for native plants and animals, and to encourage pollinators to come. But I was doing the bulk of my writing in 2020, when my daughter was home and I was responsible for overseeing her remote schooling. ... The nation was erupting. An awakening or reckoning with social injustice and disparities occurred, ... and there was a catastrophic wildfire just miles from my home. It became impossible for me not to weave all these events together. I had to pay attention to all that was happening around me.

Writing about soil, planting, and growing became a metaphor, not only for all that was growing and happening in the world, but also for your desire to unearth family history. What has digging into your ancestral soil revealed?

I can’t understand who I am right now and who my daughter can be, if I can’t fully understand who my family has been and what experiences they had that were passed along to me.

I am, as the saying goes, the wildest dreams of my ancestors. I hold their hopes and aspirations. The history of this nation is a complicated history that’s sometimes beautiful and sometimes brutal. Yet, that’s the history that grounds us. We are rooted, ... our feet are in this ground, ... we are connected to this earth, and it goes deeper than that. Our connection with the past gives us the foundation we need to move forward.

How has American soil affected African Americans’ perspectives on nature, planting, harvesting, or farming?

One of the realities of the African American community is that there are a lot of us who are deeply connected to the land, to growing, and to gardening. We are nurturing plants in our yards, containers on our balconies, and pots in our sunrooms. That aspect of the Black experience isn’t magnified in media, literature, or movies, so the connection that many of us have to the soil frequently comes as a surprise to people outside the Black community.

An insightful story from “Soil” was that Black people had to cut flowers from their own gardens to have floral arrangements for their loved ones’ funeral services; white florists wouldn’t sell them any. How did you come across that bit of history?

That’s one of the experiences my mother shared from her childhood in central Virginia. Even when white florists did sell Black people flowers, the flowers were old, subpar, wilting. Black people couldn’t go inside the store to pick what they wanted. So, Black people who grew flowers would make bouquets and create beauty from and for their community. It was a kind of collective uplift that pushed against a demoralizing and diminishing institutionalized system. Segregation was ubiquitous.

Your fondness is for a garden to be a “riot of color” rather than a monochromatic design, which you say offers the benefits of structure and order. What’s behind your preference?

So much of “Soil” operates as metaphor and fact. In the community where I live, I am a different ethnicity and color than most everybody else. It’s important to me that I live in a space that is willing to embrace the glory of diversity and difference as something that is wonderful. In terms of the garden, different pollinators are attracted to different colors, different shapes, different blooming seasons. On a practical basis, it’s useful to have many different colors, many different shapes and kinds of plants available [for] the many different forms of nonhuman life that might come to my garden. And I just find lots of color glorious!

How many different kinds of plants are in your garden?

I have no idea. Close to 70 or 80? What’s been important to me is not how many, but how much I try to get to know them and encourage them by the way I serve them. What grows is the result of a lot of hard work, research, attention, and care. About seven years ago, when I first started this project to re-wild my yard, I didn’t have nearly the level of competence or knowledge that I have now. Gardening has taught me patience. I’m willing to just see what emerges with as little intrusion as possible. There’s just enough intervention to keep things healthy and safe. But not so much that I’m commanding. Hard work, research, attention, and care are vital to parenting as well.

Life’s demands can preclude some women from cultivating their creativity. What does “Soil” have to say to those women?

I deeply interrogate throughout the book the artistic tradition that prioritizes the solitary genius – the artist who can go off by herself and create art in isolation. This is particularly problematic in environmentally focused writing because of what it says about where people are supposed to find beauty and sublimity – that the only places of true beauty are pristine, unpeopled spaces. It suggests that the quotidian aspects of our daily lives, the messiness of having to do laundry and the dishes and helping your child with homework, are not spaces worthy of creating art.

Gardens, history, and hope must all be tended, or they will be lost, you say. What are some ways to nurture those essentials?

My hope is that “Soil” is a guidebook for that work. We need to keep returning to our soil so that we can cultivate a growing knowledge of what we’re planting, a growing knowledge of our history, and a growing desire to look at the questions about how we move forward. It’s about finding ways to fully connect with nature and finding ways to build better connections with each other. We can make choices about composting, planting native plants, not using biocides. ... We can prioritize community over isolation. When we choose work that sustains our soil, our gardens, and our history, we also sustain within us a sense of hope.

Contributor Maisie Sparks is the author of “Holy Shakespeare!” and other works.