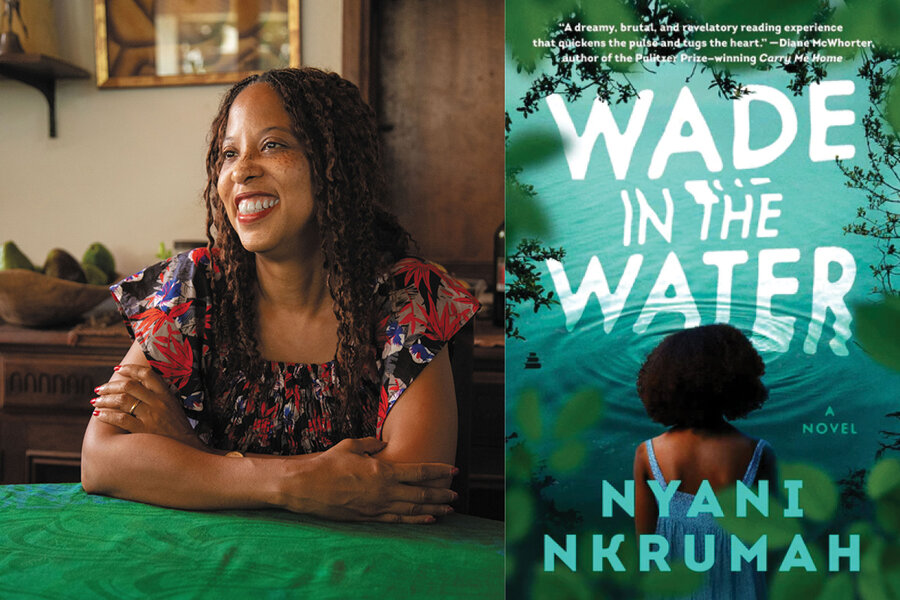

Nyani Nkrumah on racism: ‘It’s so difficult to break these chains’

Loading...

In her thought-provoking debut novel, Nyani Nkrumah takes a fresh look at the 1964 murder of three civil rights workers – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner – by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and the effect of these killings on people’s lives decades later. “Wade in the Water” explores these events through the unlikely friendship of young Ella, a smart and feisty African American girl, and a white woman, Katherine St. James, born in Philadelphia but now doing graduate research at Princeton University, who comes to live in Ella’s all-Black neighborhood in Ricksville, Mississippi, in 1982. Both hold tight to their secrets. Neither is wholly who she appears to be. Ms. Nkrumah’s book raises intriguing questions not only about Black-white relationships but also issues of colorism within the Black community. She spoke recently with the Monitor about her lifelong interest in Mississippi and how this curiosity sparked the idea for her novel.

Why did you choose Mississippi as the setting for your story?

I chose it, first, for its history, the sometimes violent interactions between Blacks and whites. But I’ve always been fascinated by Mississippi. Everything about it. Maybe this had something to do with the word itself, with the rhythm of it. The repetitive spelling. I was attracted by this from the time I was a young girl. But when I decided to look at the intersection of race and society and to what extent our past influences our future and who we are, and the roots of the legacy of racism and colorism ... Mississippi seemed like the perfect backdrop.

You provide a context for understanding racist behavior, without condoning it. How did you balance that?

I thought it was important to look at the roots of racism in a different way than had been explored. We just somehow think, “Oh, these people ... they’re just racist.” And leave it at that. But I wanted to explore a bit what happened to small farmers after slavery ended. The competition between poor whites and poor Blacks. The economic issues. I wanted to dig more deeply into that. It’s not any kind of justification but it was something I wanted to explore. And it was something Katherine St. James herself was exploring in her research where she was trying, in her own way, to defend the way that her father was.

You also raise the question not only of racism but of colorism within the Black community. Ella is the dark-skinned child in a family composed of her much lighter-skinned parents and siblings. What drew you to this topic?

Well, I mean, colorism can be a big thing in Black society. And this was one of the issues I wanted to bring up. I didn’t want to just bring up racism, which seems something to do with Blacks and whites and their relationship to each other. But I was also very interested in colorism within the Black community. I see this, also, as a legacy issue that ... still impacts us today. It has been kept alive and fed. It is so difficult to break these chains. And so I have Ella and she is very dark complected. And there is a reason why she is the only dark person in her family. Both the color of her skin and the reason for it cause her mother to feel great shame in this small community. The mother had taken, and still takes, great pride in her [own] mixed-race heritage, in the fact that her father was white. And this was another of the legacies of slavery that I wanted to explore.

When you were researching the novel in Mississippi, did you discover anything that challenged preconceptions you may have had about the state and its people?

I learned so many things about the two societies. One, which was very interesting to me, was how Blacks and whites really know each other in the South. They’ve lived together for a long time. I was talking to someone down there and I asked him about this. And he answered that it was almost like they were part of a family. Brothers and sisters. Who fuss. Who fight. Who can even do terrible things but who ultimately understand one another. He wasn’t at all minimizing the impact of the racism and the tragedies that have happened, and that happen in my book. But, in the end, he said there’s the thing that we kind of know each other because we’ve lived with each other. This was his personal opinion, but I thought this was really very interesting because I think up North we have a bit of a different perception of what is actually going on in the South.

What would you like readers to take away from your novel?

First, that the friendship between Ella and Katherine St. James was genuine. They were different in almost every possible way, but they cared for each other and learned from one another. In a sense, their friendship is the catalyst that helps them each to move forward, to know more about themselves and the reasons for some of the actions they have taken. Katherine thinks she has changed – but has she? Ella is desperately looking for love – does she find it? But by the end of the novel, neither of them has given up. This gives the novel that element of hope.