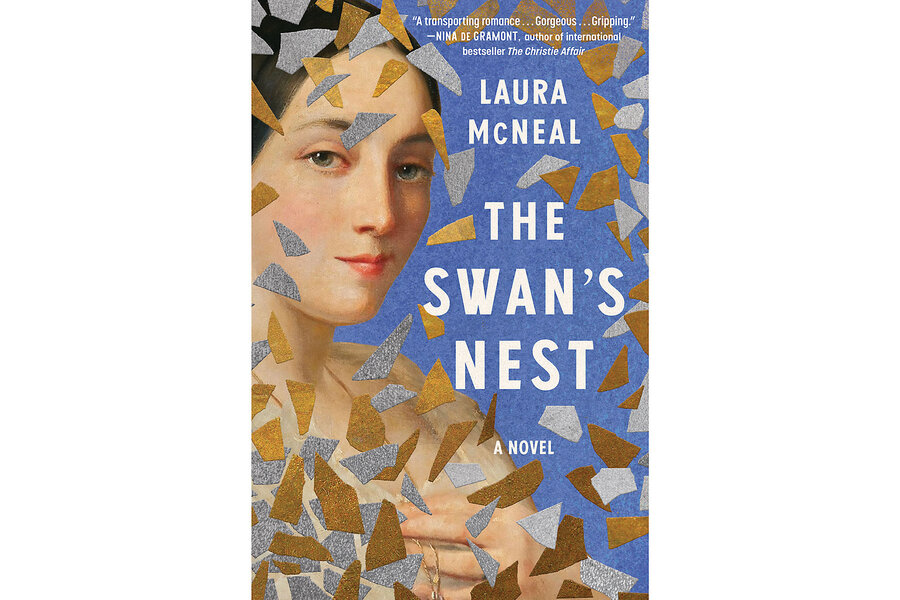

Elizabeth Barrett’s poetic love story stirs the novel ‘The Swan’s Nest’

Loading...

Sinking into “The Swan’s Nest” is like being cocooned in a down comforter.

Laura McNeal’s deeply researched historical novel is an ode to the great love between two 19th-century English Romantic poets, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning.

Her goal, as she describes it in the acknowledgments, “was to tell the story of their romance without contradicting the known record.” She found her title in “The Romance of the Swan’s Nest,” a poem that Elizabeth wrote in 1844, the year before she met Robert. Confined to her home by an undefined illness, the young poet felt she had little hope of romance or adventure beyond the page. The poem features a swan’s nest hidden among reeds that a young woman dreams of showing to an idealized lover. The eggs in the nest represent a wondrous sign of hope – an underlying theme of McNeal’s novel, along with patience, constancy, and deep trust.

Before they met in person, the two poets were drawn to each other by their writing – first through their poems, and then their letters. On the basis of Elizabeth’s poetry alone, Robert “already liked her. That far-off place you could reach only in lyric was the place she inhabited.” He felt she was speaking directly to him.

Elizabeth, nicknamed Ba, was born in 1806, the oldest of 12 children. At the start of McNeal’s novel, she is feeling stuck and restless. Her unspecified malady has kept her largely housebound for years in the third-floor bedroom of the family’s crowded London house. She and her siblings are all under the thumb of their tyrannical father, Mr. Moulton-Barrett, who disapproves of all suitors, and especially a poor poet he feels certain must be after his daughter’s money.

Elizabeth is loath to go against her father’s wishes, but Robert will not be dissuaded. He is willing to accept whatever form their relationship takes.

The source of the Barretts’ wealth is their Jamaican sugar plantation, Cinnamon Hill, a business that became less lucrative after England’s abolition of slavery in 1834. As a consequence, Moulton-Barrett was forced to sell Hope End, the family’s prophetically named Hertfordshire home.

That loss, compounded by the tragic deaths of two sons, leaves him viciously determined to defend what remains of the family fortune. He adamantly refuses to recognize claims by illegitimate offspring of family members who, when sent to the West Indies to manage their colonial businesses, frequently kept formerly enslaved island women as mistresses. McNeal enriches her novel by weaving in moral issues tied to England’s legacy of colonialism and slavery.

Fortunately for Elizabeth, despite her confinement, she has absorbing work translating Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” and penning verse for which she is celebrated. Another advantage not shared by her siblings is her independent income, a legacy from her father’s mother (and therefore also from the spoils of the family plantation in Jamaica).

The Brownings’ family life is cheerier but more modest than the Barretts’. As a young man, Robert’s father gave up a chance to get rich in the West Indies because he refused to countenance slavery. When Robert meets Elizabeth, his financial and career prospects aren’t as bright as hers. His literary reputation and sales have taken a hit after Alfred Tennyson and others declared his poems “obscure and difficult.” Elizabeth disagrees. She finds them “mesmerizing.”

Robert’s enthusiasm for Elizabeth is unbridled. In his first letter to her, he gushes, “I do, as I say, love these books with all my heart – and I love you too.” By 1846, the two poets had exchanged 573 letters in much the same vein. (Published posthumously, they are still in print.)

The lack of restraint alarms Elizabeth’s family. Was Browning a fortune hunter, or “one of those men who was always declaring that he loved someone” – including women he’d never met?

Elizabeth’s sister Henrietta grills him at a society dinner at which Charles Dickens is a guest of honor. Robert’s self-defense is robust: “What I wrote to your sister may have seemed impetuous, but it sprang from what I truly feel when I read her poems. Love, Miss Barrett, is the only word for what I feel. ... I have met her in the sense that matters to me. I know her better than many people ever know one another. Our minds are, in poems, open water. Crystal pools.”

Henrietta thinks: “It was too much. ... No one said such things and meant them – Heavens, he was like Ba.”

It’s no secret what happens – after all, “Ba” is known to this day, 163 years after her death in 1861, as Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Robert Browning, author of the much-anthologized “My Last Duchess,” has gone down in history as one of the most ardent husbands of all time. Elizabeth was no slouch at expressing her love for him either, as her 44 “Sonnets From the Portuguese” attest. (“My Little Portuguese” was a pet name for her husband.) Who hasn’t heard sonnet No. 43 – “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways” – that mainstay of wedding ceremonies and anniversary cards?

McNeal’s achievement is to dramatize how Elizabeth’s great escape from a severely limited life came to pass. In suitably lyrical language, “The Swan’s Nest” thrillingly captures a marriage of true minds and the triumph of hope, love – and poetry.