How to catch alligator poachers? Become one.

Loading...

Florida wildlife officer Jeff Babauta was nearing retirement when he went undercover to infiltrate the world of alligator poachers in the Everglades. He changed his name, adopted a freewheeling persona, and started an alligator farm on a rundown property in south Florida.

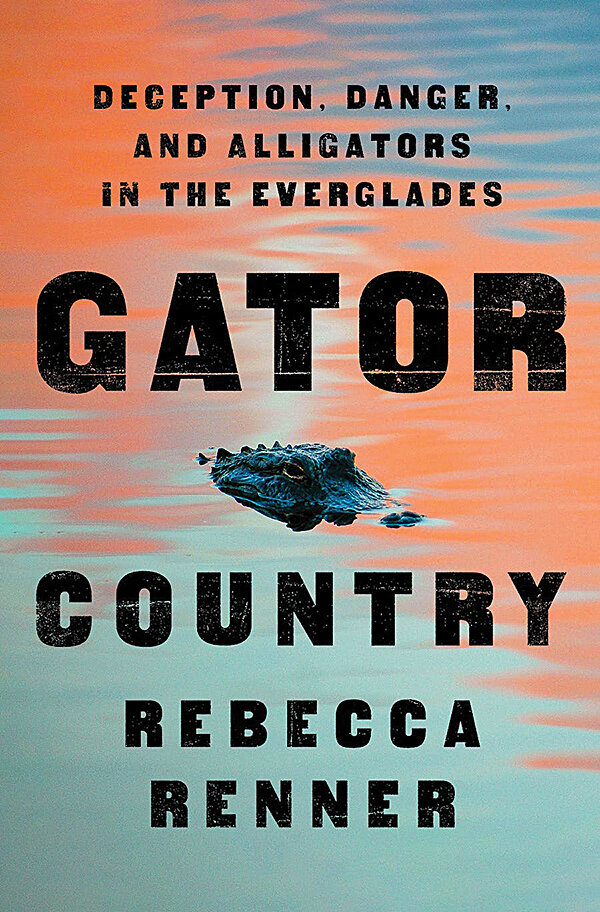

The story of Babauta and Operation Alligator Thief is the subject of “Gator Country: Deception, Danger, and Alligators in the Everglades,” Rebecca Renner’s engrossing account of a two-year sting mounted by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission in 2015. Babauta’s efforts led to the arrest of 11 poachers in a single day, one of the biggest hauls in the agency’s history.

The book’s author, a Florida native, leads the reader through the complexities of Operation Alligator Thief as well as the intriguing, often murky, biological and cultural environment of the Everglades. She has a gift for storytelling and enriches her narrative with a wealth of Florida history, local lore, nature writing, and personal anecdotes.

“I wanted to understand what it was like to be a poacher in the glades,” Renner writes. “I wanted to live the lives of rangers and wildlife officers, too. I wanted to tell a story of people. No heroes, no villains, just the desperate choices that make us who we are.”

While alligators are so plentiful today in Florida as to constitute a nuisance, they nearly became extinct in the 1950s. Their populations are sensitive, dependent on precise temperatures and water levels to assure viable egg production. Even small fluctuations in weather can have a harmful impact, leaving the species vulnerable to flooding, sea-level rise, and habitat destruction.

Flooding in the early 2010s along the Lower Mississippi Delta caused thousands of alligator nests to become unviable. To maintain their hatchling stocks, alligator farmers in Louisiana, as in Florida, relied on permits to harvest wild alligator eggs legally. With the price of eggs soaring and farmers in Louisiana turning to other sources, it was widely suspected that some farmers were buying from poachers.

Infiltrating the crime ring was no simple task for Babauta. Alligator farmers in south Florida were a notoriously closed group, suspicious of outsiders. To get information on poachers, Babauta had to become one, which meant setting up a working farm stocked with full-size alligators, about which he knew absolutely nothing. His department was tight with money, so Babauta was required to show a profit from his farm from the start. And he had to do all this while not blowing his cover, a mistake with potentially fatal consequences.

Renner’s passion for her home state is palpable and much of “Gator Country” is devoted to pushing back on misconceptions of Florida. “I was tired of reading stories that treat the glades, and all of Florida, really, as a wild and wacky backdrop where characters and tall tales abounded, where ‘normal’ folks vacationed but where real people didn’t live.”

Renner displays a genuine compassion for the people living in the Everglades, one of the poorest areas in the country. Ironically, she notes, the establishment of Everglades National Park in 1947, a worthy effort to protect the vast wetlands, came at the expense of the people who lived there, as it “pushed whole communities into crime. It pitted environmentalists against hunters, against the working-class people who lived there, the people who were already stewards of the environment in the first place. In removing the glades’ keepers, and removing their livelihoods as well, the parks struck a false wedge between the gladesmen, the Natives, and the wild.”

Part true-crime story, part memoir, part hymn to “nature’s savage beauty,” “Gator Country” makes for a rewarding reading experience.