Uncovering Shakespeare’s rare First Folios – paw prints and all

Loading...

Eric Rasmussen’s work is a combination of “CSI” and “Antiques Roadshow.” For two decades, he has traveled the globe to authenticate Shakespeare First Folios – the earliest printed compilations of the Bard’s plays.

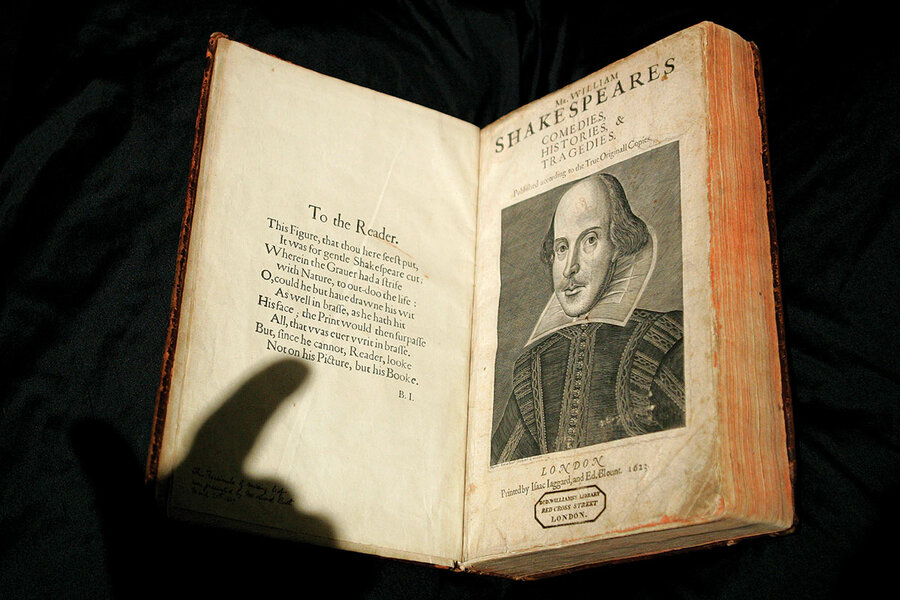

Nov. 8 marks the 400th anniversary of the First Folios’ publication, without which half of Shakespeare’s plays would have been lost.

Why We Wrote This

For the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folios, we asked an expert about his most interesting finds. He told us that each folio, or collection of the Bard’s works, is unique and loaded with history – from cat paw prints to bullet holes.

In his work, Dr. Rasmussen has encountered bumbling book thieves, eccentric owners, quirky historical footnotes, and even a copy with a bullet hole through it.

Although some scholars prefer pristine copies, he favors editions that reflect their past owners, such as the University of Glasgow folio with handwritten comments about the actors. The notes were clearly made by someone in the 17th century who saw the performance.

In another folio, a cat left five paw prints on a page opened to “Love’s Labour’s Lost.” Dr. Rasmussen surmises that the owner picked up the offending cat before it could do more damage.

Not all folios that he examines are authentic, of course. But the excitement of a potential discovery energizes his work.

His work is a combination of “CSI” and “Antiques Roadshow.” For two decades, Eric Rasmussen has traveled the globe to investigate and authenticate Shakespeare First Folios – the earliest printed compilations of the Bard’s plays – which celebrate their 400th anniversary this month. First Folios can command millions of dollars when one surfaces for sale.

Along the way, he has encountered bumbling book thieves, eccentric owners, quirky historical footnotes, and even a copy with a bullet hole through the middle (the slug stopped at “Titus Andronicus,” proving that it’s “an impenetrable play,” he says).

The folios were published in lavish fashion seven years after William Shakespeare’s death in 1616 and solidified his stardom. Without them, 18 works – including “Macbeth” and “The Taming of the Shrew” – would have been lost, says Dr. Rasmussen, a professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno. “It’s one of the most iconic cultural artifacts in the world,” he adds.

Why We Wrote This

For the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folios, we asked an expert about his most interesting finds. He told us that each folio, or collection of the Bard’s works, is unique and loaded with history – from cat paw prints to bullet holes.

Dr. Rasmussen’s Shakespeare scholarship dates back to junior high, when he wrote a report comparing “The Tempest” to “Gilligan’s Island.” He learned literary forensics at the University of Chicago, from a professor who used an electron microscope to analyze typeface variations in early texts.

“We can reconstruct what happened in a printing house 400 years ago,” Dr. Rasmussen says, including which typesetters produced which pages. Tradespeople also thought their inking equipment worked better if soaked in urine, which means their shops probably “smelled like a subway,” he adds.

In 2004, he joined forces with Anthony James West, a British business executive who spent most of the 1990s – and much of his personal fortune – tracking down surviving First Folios. Building on a 1902 census that located 152 copies – from an estimated press run of 750 – Dr. West’s legwork boosted the tally to 232. Then, at London’s legendary Reform Club, where novelist Jules Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days” got underway, he asked a research team led by Dr. Rasmussen to retrace his steps and thoroughly document the condition and provenance of each folio.

The seven-year project turned up a slew of oddities. Flipping through the volumes page by page (without gloves, which cause more damage than bare fingers, Dr. Rasmussen says), the folio detectives ran across food and wine stains, rusty silhouettes of scissors used as bookmarks, and margins scribbled with personal notes and math problems.

In one case, a cat left five paw prints on a folio opened to “Love’s Labour’s Lost,” Dr. Rasmussen says. Before the kitty could take a sixth step, it was apparently “snatched off the book,” he adds.

Although some scholars prefer pristine copies, Dr. Rasmussen favors editions that reflect their owners, such as the University of Glasgow folio in which a preface that names the actors in Shakespeare’s troupe is scrawled with comments “by someone who actually saw them perform.”

Other owners have included dukes, bishops, oil barons, a female psychoanalyst who studied under Sigmund Freud, and an 18th-century astronomer with a namesake crater on the moon.

For some collectors, possessing a Shakespeare folio has proved hazardous to their health. “A surprising number died within a year of getting their hands on one,” Dr. Rasmussen says.

Today, most First Folios belong to museums, universities, or libraries. No two copies are alike, thanks largely to typographical errors that got fixed as the press run continued but still made it into print because the paper was expensive and flawed pages weren’t discarded.

In 2011, the idiosyncrasies and histories of each folio were chronicled in two books based on the research of Dr. West and Dr. Rasmussen’s team. The first, a 600,000-word reference, “The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue,” inventoried in “retina-detaching detail” (as one critic put it) every watermark, crease, tear, margin note, and more. It’s the literary equivalent of a fingerprint, Dr. Rasmussen says. The second book, “The Shakespeare Thefts: In Search of the First Folios,” recounted stories for a nonacademic audience.

In recent years, three more First Folios have surfaced – along with a few false alarms – and Dr. Rasmussen commonly gets called to investigate.

“He is a trusted expert – by scholars, auction houses, libraries, and bibliophiles,” says Emma Smith, a Shakespeare authority who has written two books on First Folios and authenticated one of the newly discovered copies. “No one else I can think of has his credibility with these different groups.”

Ayanna Thompson, director of the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, agrees: “Professor Rasmussen’s work has been invaluable for our understanding of First Folios.”

And wannabe First Folios.

Over the last century, news reports periodically swirled that a civil engineering college in Roorkee, India, had a copy – and the book’s dimensions were larger than any other First Folio. Yet no experts had managed to inspect the relic.

Finally, last year, after a new round of articles, Dr. Rasmussen hopped on a plane to settle the issue. Flower bouquets, gifts, and photographers greeted his arrival at the school’s Mahatma Gandhi Central Library, where he was whisked to a gallery that also houses a signed copy of India’s Constitution.

To his surprise, the folio was in tatters. “The fragments reminded me of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” he writes in “Shakespeare’s First Folio Revisited,” a 400th-anniversary collection of essays. “In a moment of romantic reverie, it seemed to me that surely only a survivor from the early 17th century, one that had long endured the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, would be found in such a state.”

But alas, poor Yorick, when Dr. Rasmussen powered up his portable light box – a device normally used for viewing photo negatives and slides – and backlit each of the folio’s 908 pages, he couldn’t find any of the 21 telltale original watermarks. The verdict wasn’t all bad for his hosts, however. Although Dr. Rasmussen concluded the volume was a 19th-century replica, he tagged it as one of the first created via photolithography. That’s rare too, he notes.

A book doesn’t have to be a First Folio to hold a silver lining.