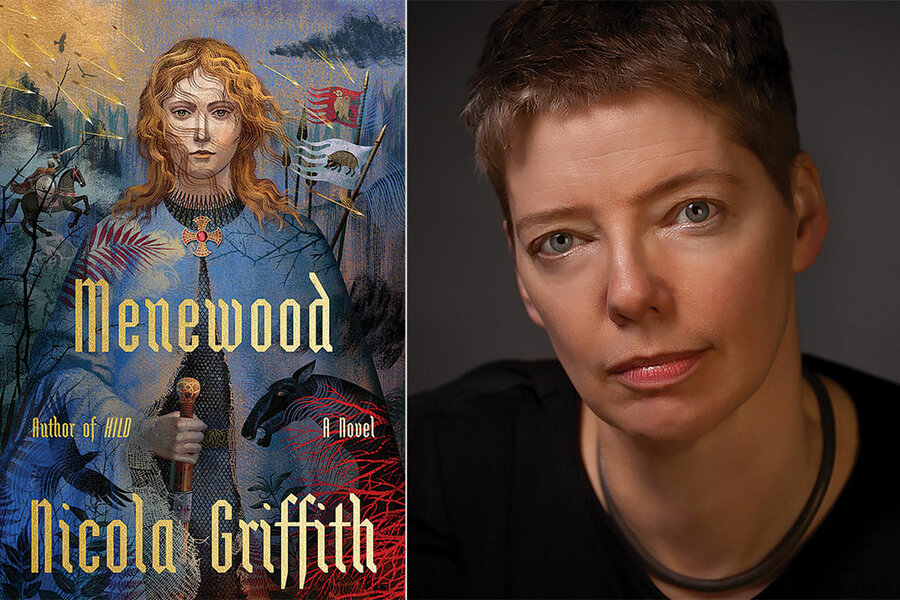

Going medieval: A novelist discovers her muse

Loading...

Growing up in Yorkshire, England, author Nicola Griffith felt the pull of the past: “Every horizon has a mark of history on it,” she says.

A visit to the ruins of Whitby Abbey in North Yorkshire first acquainted her with St. Hilda, the seventh-century noblewoman who founded the abbey. Little is known about her life, other than a tantalizing description of her as an adviser to kings.

Why We Wrote This

Historical fiction can offer an escape from modern stressors. But for this author, re-imagining the past offers new ways to explore moral and societal struggles that endure today.

So began the author’s decadeslong passion to write the story of Hilda, or Hild, as she was also known. The young woman she imagines is no saint – yet.

Ms. Griffith spoke about the character’s trajectory, from the first book in “The Hild Sequence,” 2013’s “Hild,” to “Menewood,” published this month, about Hild’s secret community, which she hopes to keep safe from warring kings.

Growing up in Yorkshire, England, Nicola Griffith felt the pull of the past: “Every horizon has a mark of history on it,” she says. A visit to Whitby Abbey first acquainted her with St. Hilda, the seventh-century noblewoman who founded the abbey. Little is known about her life, other than a tantalizing description of her as an adviser to kings. So began the author’s decadeslong passion to write the story of Hilda, or Hild, as she was also known. The young woman she imagines is no saint – yet. Ms. Griffith spoke about the character’s trajectory, from the first book in “The Hild Sequence,” 2013’s “Hild,” to “Menewood,” published this month, about Hild’s secret community, which she hopes to keep safe from warring kings.

When did you first learn about the real Hild?

I love old abbeys, old castles, all that kind of thing. But I had never been to [the ruins of Whitby] Abbey until I was in my early 20s. I crossed the threshold of the abbey, and it was like stepping into Narnia. The world just changed. You know when some people talk about the skin of the Earth being thin in some places, this sense of immanence? It was like that for me.

Why We Wrote This

Historical fiction can offer an escape from modern stressors. But for this author, re-imagining the past offers new ways to explore moral and societal struggles that endure today.

I read in a tourist pamphlet about St. Hilda of Whitby, who founded the abbey, and I wanted to learn more, but there were no books about her.

My question was, why is this woman, from a time when we’re told that women had no power, no influence, no significance whatsoever, still remembered 1,400 years later? Nobody could tell me. I was on fire to find out; I thought what we knew of history must be wrong. This could not have happened if what we think of as history is actually true. So I basically started this enormous controlled experiment. I rebuilt the seventh century. I mean, I researched before I even wrote a word.

I’d been researching that book [“Hild”] for 20 years. I’d been reading everything you could possibly think of, all the medieval plants, everybody’s lists of grave goods. I followed all the archeology magazines and blogs and journals, and I read about the weather. I researched the flora, fauna, jewelry, making textiles. And then the day before my birthday, I thought, I cannot start another year without having done this book. So I sat down and said, I’m going to write one paragraph. And so I did. And there was Hild. And she was 3 years old and sitting under a tree. And I thought, that’s how I’m going to do it. She’s going to learn the world along with the reader.

When you came to write the character, how did you imagine her?

Hild is not a saint. I mean, yes, she becomes known as a saint, but she is not a saintly person growing up. She kills people [when necessity dictates]. ... She is not always as kind as she could be. But she can see how [her] actions affect people. She can see how terrible some choices are for [those] who are caught in the crossfire of powerful people. Still, she really loves life. She loves to wring every drop of joy from life that she can.

What does Menewood signify?

Hild has this inkling that trouble is coming. And so she makes this haven. Menewood is a secret [community]; it’s safe, it’s all hers – no one can mess with it. And it all just grows organically. It’s not like she sat down [and envisioned] a Utopian space. That’s not what she’s doing. It begins as a kind of selfish impulse, a survival strategy, and then gradually it becomes clear that in fact, people work better if they’re well fed and feel happy and have a say in decisions.

In a book that’s over 700 pages long, many characters come and go. How did you think about the ancillary characters?

The books I love best are the generous books where you get a sudden, deep, focused dive into a person that you will never see again. And it doesn’t have to be long; it’s maybe two sentences. Suddenly, you know who they are, what their life is like. And it adds to this reality, this texture of the world.

There was tremendous violence in Hild’s world, that she witnessed and participated in. People were fighting for control of territory and it was quite brutal. Hild is part of that world and can speak that language. But it feels like she would avoid the violence if she could. Or would she?

She wouldn’t choose to kill people. It’s not fun for her, but [killing is] very much a tool. It’s a necessary tool. There is a sense of necessity to certain sets of violence [in this era]. It’s not that violence is enjoyable or that it’s casual, but it is not as abhorrent as it would be to most of us now.

Hild knew how use weapons, she understood military strategy, and she was highly competent in so many areas. Do you think that women in the seventh century were more competent than they are given credit for being?

I can’t imagine how society would have worked if women were not allowed to be physically competent. It was women who handled the sheep and did the massive physical work of textile production. They were acknowledged to be strong. In the early seventh century, the world was precarious enough that everybody needed to pull their weight.

The battle scenes are cinematic. Were you playing them in your head?

I have an active imagination. [Laughs]

For example, the big battle toward the end of “Menewood,” I have read Bede’s account of that. And of course he believes that the winner was able to win because of God. And I’m like, OK, so if we take God out of the equation, what happened? Really, what could have happened? How could this have been possible? Because on paper it’s impossible. What happened was impossible except by divine intervention. And so I thought about, OK, where was this battle? What time of year was it? What would it be like to stand on one of those hills? To look at these rivers and birds. What would it feel like? What would it smell like?

Are there lessons for today in the kind of life that Hild is leading and how she leads?

What Hild lives is applicable to everyone everywhere, which is basically treat everybody as a real person. Everybody has their own feelings. And the other important part is that no one can do it on their own. You need your friends; you need your family; you need your community.

Will there be more to Hild’s story?

I think the next book is going to take her to the beginning of her religious life. And then the fourth book will be about her religious life.

What do you like best about the character?

Hild never dithers. She can be in fear for her life, but she’s never anxious. She doesn’t second guess herself all the time.

I think I’ll be writing Hild for the rest of my life. I love it. It’s the work of my life.