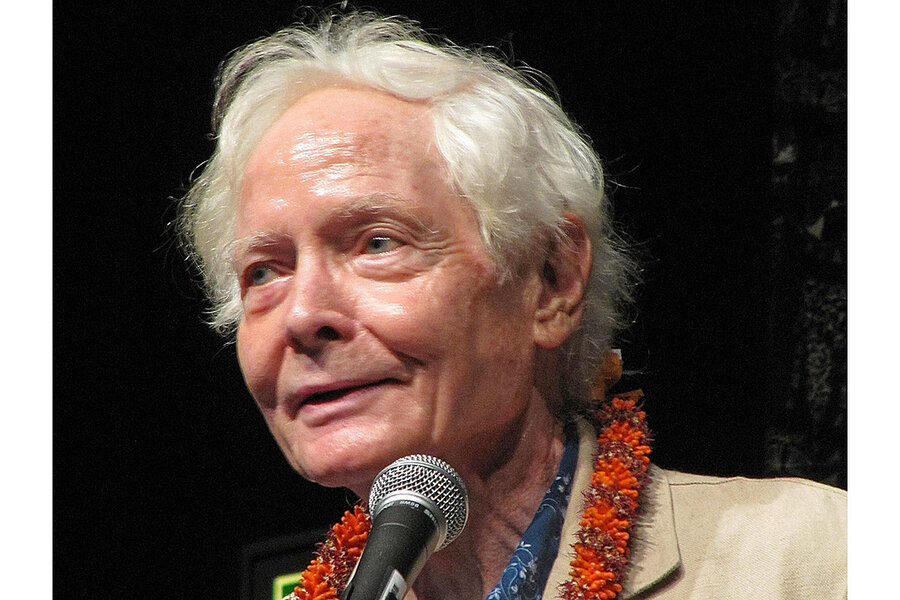

Poet W.S. Merwin followed where the words led

Loading...

Every morning W.S. Merwin sat down to write on scrap paper. “It has to be a piece of paper that is worthless,” he noted in a phone interview in 2003. “The idea of taking a blank sheet would be very intimidating.”

It is a surprisingly humble admission, given that Mr. Merwin, a U.S. poet laureate, is one of the most prodigious, prolific, and decorated poets of his generation. Recipient of two Pulitzers, a National Book Award, and many other honors, Mr. Merwin was lauded for his dozens of volumes of poetry, including “The Carrier of Ladders” and “The Shadow of Sirius,” for which he received the Pulitzers.

Why We Wrote This

Once called “the Thoreau of our era,” W.S. Merwin was an environmentalist who transformed concrete language into evanescent poetry that reflected on war, spirituality, and the natural and metaphysical worlds.

The son of a Presbyterian minister, he enlisted in the Navy, discovered he was a pacifist, and then decamped to Europe. There, he worked as a tutor and translator before returning to the U.S. and eventually settling in Hawaii, where he found purpose in environmentalism and Zen Buddhism.

Over time, his style evolved from tight, image-driven poems to longer, experimental works, and from classical subjects to political and ecological concerns and, later, to metaphysical inquiries. What remained consistent throughout his career was his willingness to follow where the words led, and his commitment to preserving the natural world.

Since Friday, when poet and translator W.S. Merwin died at his home in Maui, Hawaii, I’ve been thinking about the phone interview he gave me in 2003.

“Poetry can’t be done as an act of will. You can’t say, ‘I will now write a poem,’” he noted early in our conversation. Yet every morning he sat down to write on scrap paper. “It has to be a piece of paper that is worthless. The idea of taking a blank sheet would be very intimidating.”

I was surprised by that humble admission, given that Mr. Merwin published more than 50 books in his lifetime. Like many poets, he often began with a sound, “some phrase or sentence that suddenly seems to be very much alive, but I don’t know where it is going. I find out by listening.”

Why We Wrote This

Once called “the Thoreau of our era,” W.S. Merwin was an environmentalist who transformed concrete language into evanescent poetry that reflected on war, spirituality, and the natural and metaphysical worlds.

Over time, that listening led Mr. Merwin, the son of a Presbyterian minister, to evolve from writing tight, image-driven poems to longer, experimental work, and from classical subjects to political and ecological concerns and, later, to metaphysical inquiries. It also helped him become one of our most decorated poets, beginning with his first book, “The Mask of Janus,” which was chosen by W.H. Auden for the Yale Younger Series in 1951. Mr. Merwin won his first Pulitzer Prize for “The Carrier of Ladders” (1971); the National Book Award for “Migration: New and Selected Poems” (2007); and his second Pulitzer for “The Shadow of Sirius” (2009). He also served as the nation’s 17th Poet Laureate Consultant of the United States in 2010-11.

What remained consistent throughout his career was his willingness to follow where the work led, and his commitment to preserving the natural world.

During our conversation, he mentioned that after he finished writing, he would plant a few palm trees on his 19-acre home in Maui, Hawaii, slowly reclaiming land that almost had been ruined when it was used to raise pineapples in the 1930s.

What was so appealing about palm trees, I wondered.

“You can fall in love with palms because they’re incredibly ancient. They go back at least 60 million years, yet they’re still evolving,” he explained. Also, “Palms can be grown quite close to each other, and when they grow up they make a canopy, but they work out their relationships with each other very well.”

Mr. Merwin, who began studying Buddhism in 1970, worked through many essential questions in his writing. As the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “W. S. Merwin is one of the greatest poets of our age. He is a rare spiritual presence in American life and letters (the Thoreau of our era).”

His metaphysical approach shaped even short poems in his later work, as with the lovely “Rain at Daybreak,” published in his final book, “Garden Time” (2016):

One at a time the drops find their own leaves

then others follow as the story spreads

they arrive unseen among the waking doves

who answer from the sleep of the valley

there is no other voice or other time

His contribution to American poetry is profound. When I think about how his work has impacted me and many other writers, the opening lines of “The Wings of Daylight,” another poem from his final collection, immediately come to mind:

Brightness appears showing us everything

it reveals the splendors it calls everything

but shows it to each of us alone

and only once and only to look at

not to touch or hold in our shadows

Poems used by permission of Copper Canyon Press.

Elizabeth Lund writes about poetry for The Christian Science Monitor and The Washington Post.