Coup attempt threatens Madagascar's uneasy path to democracy

Loading...

| Antananarivo, Madagascar

Eighteen months after a military coup d'état brought him to power, Madagascar's president, Andry Rajoelina, is setting the stage to transfer power through elections.

Former presidents – toppled in coups or by contentious votes – are talking of returning from exile, opposition groups are becoming increasingly vocal, and a new and apparently independent election commission is printing ballots and readying polls for a four-stage series of elections, beginning with today's constitutional referendum. But is Madagascar ready for its return to democracy?

"We are ready for this election," says Yves Hery Rakotomanana, head of the National Independent Electoral Commission. Nothing should delay the votes, he adds, not even the logistical nightmare of holding elections during the country's six-month-long rainy season. "We don't have a choice. We have to have an election. For us, what we are looking for is a clean election. If the election is a mess, then Madagascar will go down."

The consequences of coups

The coup that toppled Madagascar's last elected government in March 2009 made little noise on the world scene. Power shifted from one elite to another; peace negotiations were held, then collapsed; and Madagascar's mining industry slowed to a crawl. Yet any coup in Africa is troubling, Western diplomats say, because it lowers the standard of behavior for neighboring regimes. And any election, even if flawed, offers a chance to end the political crisis that keeps the country poor.

"We have had a year-and-a-half of transition that was not dictatorial, but it was not stable either, so we in the international community say that we need to restore democracy," says a Western diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity in Antananarivo, the capital. "If Andry doesn't ruin this, then that may allow a new generation to come to power."

In Madagascar, those are hopeful words. Nearly 70 percent of the population, 14 million citizens, live below the poverty line. Some 1.3 million survive on daily international food assistance. Anything that creates instability, scares off investors or tourists, and slows the economy is unwelcome.

But in a country where power bounces among elite groups like a beach ball, true stability will come only through fundamental changes in how power is distributed, experts say.

"We're at a moment when the state itself is in danger; it is not able to provide the most basic services of health, education, sanitation, and security. Military discipline is completely breaking down," says Charlotte Larbuisson, regional analyst for the International Crisis Group.

Free and fair presidential polls?

Two or three of the more recent presidents of Madagascar may be returning to take part in the upcoming elections, supporters say. Presidential elections are currently scheduled for May 2011, following mayoral elections in December and legislative elections in March 2011.

"We are moving toward national reconciliation and forgiveness between Madagascans," Fetison Rakoto Andrianirina, a spokesman for former President Marc Ravalomanana, told supporters at an Oct. 18 rally. "The proof of this is the imminent return of the two presidents who have been in exile."

Still, some opposition activists say they are skeptical that the current elections will be free and fair. "We are not against the principle of elections as a way out of the crisis," says Pierrot Rajaonarivelo, a former finance minister in the government of Mr. Ravalomanana. "What bothers us is the timing. No one has a copy of the Constitution, not even the officials themselves."

Opposition activists also point to what they say is bad faith on the part of the Rajoelina government in the way that opposition rallies tend to be shut down by police, such as one on Oct. 18 in the capital that was dispersed with tear gas.

Government officials loyal to Rajoelina say nothing will stop the elections from taking place, and yet they continue to defend the coup, especially against criticism from their neighbors in Southern Africa.

"One has the right to strike if one feels his liberty is not respected, so we had the right to take the future in our hands," says Hajo Andrianainarivelo, who, as minister of land management, has one of the most coveted jobs in this island nation.

"As for SADC [the Southern African Development Community]," he says, wrinkling his nose, "we don't need democracy lessons from the likes of Zimbabwe or Swaziland." Zimbabwe held deeply flawed elections in March 2008, which led to a tense coalition government, and Swaziland is Africa's last remaining monarchy.

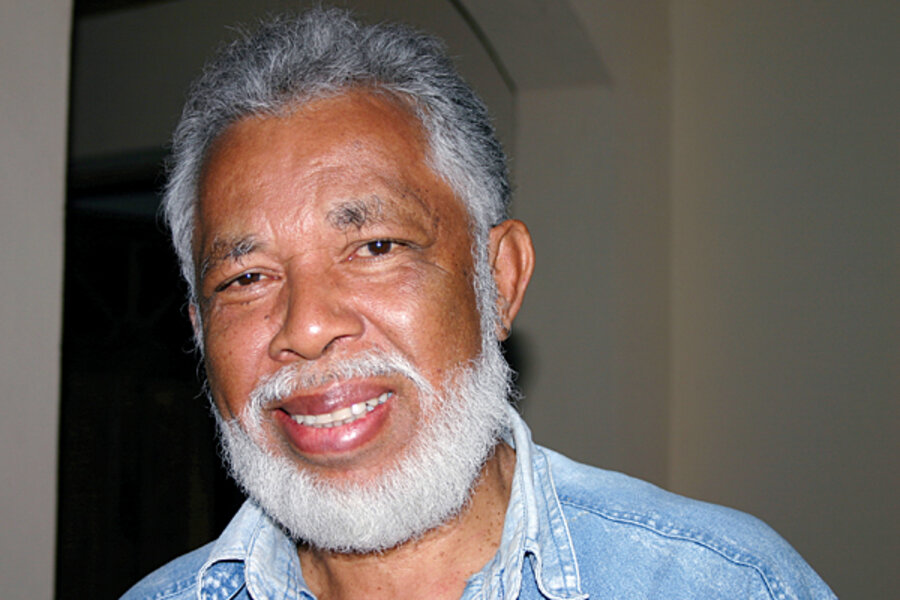

In between the government and opposition groups are local mediators such as Pastor Paul Ramino.

"We have to know that our first president, Philibert Tsiranana, was elected with 99.99 percent of the vote, and two months after that, he was thrown out of power," says Pastor Ramino, president of a council of elders called the Raiamandreny Mijoro. "All presidents think they will stay forever. They never think that Main Street people can throw them out…. But it is God who governs this country, not men," he says with a smile.