My ride? It’s a power plant

Loading...

| Newark, Del.

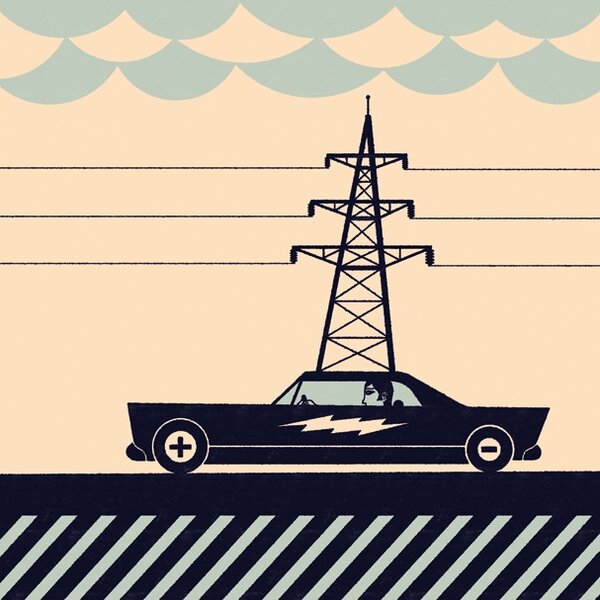

Dragging an inch-thick power cord from a curbside charging station to his all-electric-drive car, Willett Kempton plugs it into a socket just above the vehicle’s front bumper and flashes the tiny smile of a man who thinks he knows something others do not.

Perhaps he does. The University of Delaware professor’s test car isn’t merely charging up – it’s potentially sending power the other way, too.

A computer inside the car communicates with the giant Eastern PJM power grid. Through the connection, PJM can ask for extra juice from the car’s battery to balance fluctuating demand on the grid. The car’s dashboard computer checks the vehicle’s battery level and – if there’s enough charge to drive home – can sell the excess energy back to the power company at a profit.

While a handful of such vehicle-to-grid (V2G) research projects have emerged from California to Texas to Colorado, Dr. Kempton’s project has driven the farthest.

For more than a decade, Kempton has researched, lobbied, and agitated for these “cash-back cars.” His and other in-depth studies describe a future where electric-car owners plug in at malls, hardware stores, or home garages and earn $1,000 to $2,500 annually for the power they pump back into the system.

Such “regulating power” to help balance grid fluctuations is valuable – recently about $42 an hour for one megawatt’s worth. One car can’t do that much, of course. But 60 cars might – and still remain charged up enough to easily get where they need to go.

Kempton’s dream took a small but critical step closer in January when Newark, Del., became the first US city to license a V2G recharging station.

The scheme’s potential for millions of cars to act as a communal backup for the grid has finally caught the attention of utility operators, Detroit automakers, and even Washington policymakers.

President Obama mentioned V2G on “The Jay Leno Show” last month, though he avoided the wonky acronym. Jon Wellinghoff, the new chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, says the nation’s shift to renewable power will require a growing V2G fleet. Because wind and solar power fluctuate throughout the day, it could destabilize the grid without a battery backup. Also cheap wind energy captured at night could be stored in millions of V2G vehicles for use during the day.

“These vehicles are a vital part of US energy security and our ability ultimately to provide for the economic stability of the country,” says Mr. Wellinghoff, an unabashed V2G backer and the man many credit with coining the term “cash-back cars.”

By this summer, Kempton’s consortium expects to deploy its first five V2G cars. Up to 200 more vehicles – retrofitted by conversion companies – could be on the road by next year, he predicts.

“If we have 200 vehicles in our fleet, they’ll sign a contract and start writing us checks,” Kempton says of the PJM grid operator.

At that point, his group will try to form a “coalition” of V2G-car owners that can provide PJM with one megawatt of on-demand power.

With Newark as hub, Kempton sees this first V2G coalition becoming a prototype for one day aggregating millions of cars nationwide into similar coalitions, each offering car owners a certain rate per hour to plug in their car.

“We’re still at the beginning of things,” says Ray Dotter, a spokesman for PJM, which serves 51 million people across 13 states. “There’s just this one V2G vehicle out there now – and we’re embracing it and its potential.”

A ‘chicken and egg’ problem

Many hurdles remain. Where will V2G vehicles and charging infrastructure come from – and who will pay for them? To be truly effective, V2G will require heavy-duty 240-volt plugs and connections similar to those on an electric dryer.

Also, while many utilities now embrace the idea of charging up plug-in hybrid cars – it’s a big new market for power after all – there is less enthusiasm over V2G. Safety concerns and the complexity of tracking power usage and assimilating power from potentially millions of vehicles is daunting.

“Utilities still need to understand the business case for V2G,” says Mark Duvall, a manager for the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). “What are the requirements for hundreds of thousands or millions of vehicles all doing their thing with power coursing through the system?”

Automakers are another critical component. Detroit seems to be cautiously opening the door to both all-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids such as the Chevrolet Volt – expected in 2010. General Motors and eight other automakers have plans for at least a dozen such vehicles to hit the market by 2012.But will they be V2G ready with the right plugs and software?

“I think the automakers think that V2G is going to happen,” says David Cole, chairman of the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Mich. “It’s ... going to gain traction over the long run.”

Yet even Kempton admits that none of the auto officials he’s spoken with seems particularly enthusiastic about V2G. Some worry that the battery life of vehicles will be lessened by constant draining and recharging.

“We are exploring many vehicle-to-smart-grid options,” Robert Kruse, head of vehicle engineering, hybrids, electric vehicles, and batteries for GM writes in an e-mail. Still, “the idea of using battery life to provide power to the grid is problematic at best.”

While retrofitting works for small fleets, large-scale V2G needs the support of automakers, says EPRI’s Mr. Duvall. But, they “aren’t going to do it until they believe the battery will last the life of the vehicle.”

Kempton acknowledges that battery life could be affected, yet notes that battery leasing and power management can reduce the risks and still make the V2G proposition pay.

The business model

George Parsons, a University of Delaware economist and part of Kempton’s 15-member team, is surveying consumer attitudes about the critical trade-offs between driving range, the time it takes to charge, gasoline costs, and pollution reduction.

“Of all the surveys I’ve done, the V2G question is one of the most complex,” Dr. Parsons says. “If you can afford to buy a V2G vehicle, will people care about the cash enough to plug it in all the time?”

Meanwhile, Nathaniel Pearre, a research assistant, is analyzing actual driving patterns in a huge database to see how many V2G vehicles could be expected to plug in at any given time of day. While about 57 vehicles with high-capacity batteries could provide one megawatt of power, 200 vehicles will probably be needed to meet the demand since others could be on the road or unplugged, he says.

“It’s highly variable and fluctuating until we reach the size of a fleet,” Mr. Pearre says. “The first vehicle manufacturer that offers this kind of value to their clients is going to clean up.”

Keeping track of how much power an individual car supplies to the grid – and how much its owner should be paid – no matter where the vehicle is plugged in is another hurdle for Kempton’s team.

Even so, “it is probably a little easier than keeping track of minutes used on cellphones, which have to work while they are dynamically moving,” says Keith Decker a computer science professor at the University of Delaware. “The cars don’t have to move while they are part of the system.”

His team is developing algorithms that will not only undergird the accounting, but turn cars’ dashboard computers into “smart agents” that predict – based on driving patterns – how much battery power they will have to sell tomorrow or next month. Such knowledge is critical to any power contract.

V2G cars on the road

With Kempton’s team pulling together the knowledge base, Tom Gage, president of AC Propulsion of San Dimas, Calif., is the mastermind behind the all- electric “E-box” vehicle. His company has converted a handful of Toyota Scions into all-electric-drive vehicles with V2G software and connectors.

A handful of these 120- to 150-mile-range vehicles have been built so far at a cost of about $70,000 each. The E-boxes have about 36 kilowatt hours of power, more than double the battery capacity of a Chevy Volt. Prices could fall as low as $39,000 per vehicle as battery and vehicle volumes grow, writes Leonard Beck, a V2G expert at Eastern utility company Delmarva Power in his book “V2G-101.”

Mr. Gage’s company is right now building 500 potentially V2G capable Mini E’s for BMW. But the German automaker would need to include V2G software, which it hasn’t done, Kempton says.

Not willing to wait, Kempton has lined up car customizer Autoport to begin converting Scions into all-electric vehicles using AC Propulsion technology.

Despite remaining hurdles, Kempton is upbeat. “We’re just beginning,” he says. “We’ll get there.”