Inherent Vice

Loading...

I quarreled with Inherent Vice, the latest novel from the reclusive Thomas Pynchon. I liked its wit, style, and grasp of locale, but deplored its cavalier way with plot. The book confounds, entertains, and stumbles in almost equal measure.

It aims to be a celebration of a somewhat seedy, often-stoned private eye, presented in glorious Technicolor. It unfolds in the dawn of the 1970s in a Los Angeles reeling from the Tate-LaBianca murders. It would be daring – but winds up merely nostalgic.

Pynchon does not treat that lurid, Manson-defined period with gravity; rather, he spins a convoluted, insistently light-hearted procedural in which private investigator Doc Sportello comes to grips – and terms – with the Golden Fang, a fantasy, a cartel, a refuge for corrupt cops, you name it. Like Pynchon’s Los Angeles, the Golden Fang comes in and out of focus. So do many characters, like Shasta Fay Hepworth and Penny Kimball, Doc’s main squeezes, and Michael Wolfmann, the shadowy real estate developer Doc aims to track down.

I won’t reveal the ending, but it’s wistful and very southern Californian, like the stylish, period dialogue and neon characterization. “Inherent Vice” is a real departure for Pynchon, who’s known as much for the length and density of his books (“V” and “Gravity’s Rainbow,” in particular) as their rarity. (This is his sixth novel in a 49-year career). Here, however, he keeps things relatively simple. “Inherent Vice” aims to be a thriller, and if Pynchon’s tone undercuts that, it also makes it unusual.

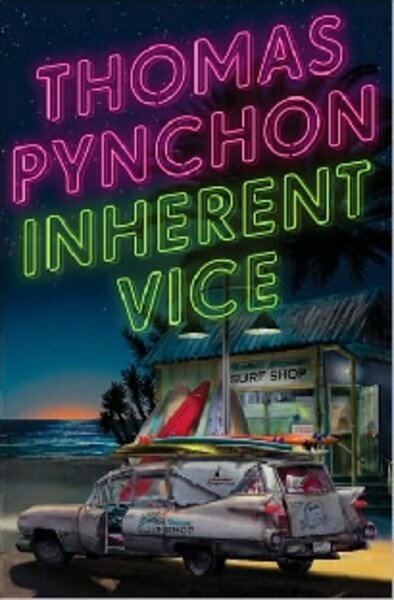

The alluring cover art, depicting a graffiti-heavy Cadillac hearse in front of a surf shop, contrasts with what’s inside. The cover, all early Beach Boys, evokes a mythical California of sand and sun, a place where hippies can toke up, lay back, groove to all kinds of music (Pynchon’s naming a rock group Carmine & the Cal-Zones is inspired) and romance the day away. Between the covers, however, the book enters darker, Frank Zappa-like territory.

And darker types appear, like Puck Beaverton, a thug with a swastika tattooed on his head, and Bigfoot Bjornsen, a Los Angeles cop of conflicting loyalties. Some of these characters are candidates for redemption, like Coy Harlingen, the junkie tenor sax player who decorates various subgroups, and Doc’s girlfriend Shasta, who takes many detours but somehow manages to hew to emotional true north.

Like a Firesign Theatre play, “Inherent Vice” crosscuts characters and plot lines, effectively shedding all notions of linear development in favor of complexity and provocation. Among the topics it touches on: the embryonic Internet, vigilante groups local and national, futuristic architecture, the monitoring of cults, resurrection, lost continents, intoxicants faux and authentic, dollars with pictures of Nixon on them, the “Mormon mob” said to run Las Vegas, witness protection. Pynchon mixes these all together to keep the reader interested, and it works, almost compensating for the numerous, confusing plot lines. But in striving for the cosmic, Pynchon failed to write about anything in depth.

I suspect that he wrote “Inherent Vice” in hopes of aligning himself with today’s readers; I don’t feel he invested much in his characters, who rarely transcend cartoon level. He already has set up an “Inherent Vice” wiki, a kind of online index with which to track the characters. This will launch on the date of publication in early August, modernizing a book that, despite its hipness and creativity, feels strangely old-fashioned. It will join other wikis dedicated to his novels, nurturing a sense of community under the banner of metafiction.

But the novel must stand alone, and it does so in some ways. I like the wit, the lingo, and the sense of place in “Inherent Vice.” I love some of the names, like Trillium Fortnight, and El Drano, Pynchon’s laser-sharp sobriquet for a heroin dealer. I like the way Pynchon evokes the experimentalism of the ’60s, when hippies got high (or tried to) on everything from LSD to morning glory seeds to the scrapings of banana peels.

How descriptive Pynchon can be is clear in this riff on Vegas: “Doc got out and strolled under a Byzantine archway and into the seedy vastness of the main gaming floor, dominated by a ruinous chandelier draped above the tables and cages and pits, disintegrating, ghostly, huge, and, if it had feelings, likely resentful – its lightbulbs long burned out and unreplaced, crystal lusters falling off unexpectedly into cowboy hatbrims, people’s drinks, and spinning roulette wheels, where they bounced with a hard-edged jingling through their own dramas of luck and loss.”

This paragraph alone suggests worlds Pynchon could explore. If only he had settled on one (okay, maybe two, for the counterpoint and drama) in “Inherent Vice.”

Carlo Wolff is a free-lance writer in Cleveland.