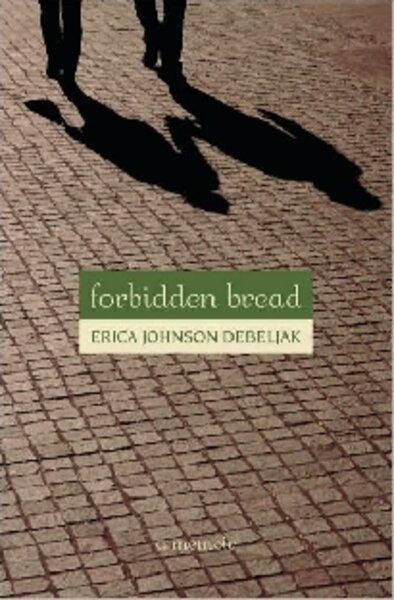

Forbidden Bread

Loading...

When Erica Johnson Debeljak told friends and family that she was getting married and moving to live near her fiancé’s family, she didn’t receive the hugs and cries of joy that most newly engaged women expect. What followed instead was a moment of stunned silence – succeeded by horrified questions and dire predictions.

“Isn’t there a war going on over there?” and “You will have to don the chador, no?” she was asked. And, perhaps most chillingly, your husband-to-be, she was told (by someone in position to know), “will never lift a finger.”

As a reader I must confess that I, too, expected nothing short of doom when I picked up Forbidden Bread, Debeljak’s jaunty, engaging memoir about her courtship and marriage. After all, this is the story of “a New York woman, a financial analyst, who against her own judgment and the judgment of pretty much everybody else that she knows, marries the most flagrant womanizer she’s ever met, a poet of all crazy things, and moves to his tiny new country halfway across the world” – Slovenia.

And yet, Debeljak points out, “Sometimes ... miracles happen.”

Debeljak’s last name was Johnson the night in 1991 when she met Aleš at a party in Manhattan. He was a student in the US, but preparing to return to his homeland, the freshly minted country of Slovenia (formerly the northernmost province of Yugoslavia). Debeljak was thrilled by Aleš’s foreignness.

He, meanwhile, snubbed her to pursue other women.

They did, however, finally meet up for dinner one night a few weeks later. But as they ate he quoted a Slovenian proverb, dismissing any attraction between them as the mere thrill of “forbidden bread.” They did, Debeljak admits, seem a comic mismatch of stereotypes: “he the poor and noble son of socialism, and me the pampered daughter of capitalism.”

By all rights, their romance should have ended there. Soon, Aleš went home to Slovenia, breaking up with her at least four times along the way. Somehow, however, she couldn’t let go. And every time she was about to, something seemed to push the unlikely love affair back on track.

The next year, Debeljak took the plunge and married Aleš, propagandizing wildly to family and friends as she went. Slovenia has “an amazingly egalitarian system,” she insisted. It has “kept everything that is good from socialism and gotten rid of all the rest.”

When her side showed up for the wedding in Ljubljana, the country’s capital city and her new home, she made sure that they saw the charming baroque and medieval city center, and not the “poured slabs of gray concrete with the occasional window hacked out of them” that constituted much of the rest.

The truth about her new home was that, “The weather was bad, the meat overcooked, the toilet paper came in rough little squares.” Cabbage patches lined the edges of the still-agrarian metropolis and the smell of manure lingered in the air. Slovenians, it seemed to her, smoked incessantly and glared unsmilingly at foreigners.

In addition, while the friend who imagined she’d be donning the chador was wildly off base, the ones who worried about war were not. The siege of Sarajevo was under way and, among other things, Debeljak had to worry about the sound of gunfire interrupting her wedding vows.

And yet, somehow Debeljak embraces each challenge as an adventure. She plunges into study of the complex language (accepting her language teacher’s mantra, “Never ask why”), charms her new in-laws, and manages to eke out a reasonable social life in a country whose entire population is less than that of Brooklyn.

“Forbidden Bread” is a sunny, can-do look at intense culture shock. Debeljak makes a humorous, self-effacing guide to her own story and the only complaint I have is that I wish she’d told us more.

Was it all really so breezy and bright? Or does Debeljak simply shorthand to prevent her tale from bogging down in a more complex accounting of events, especially when it comes to family ties and relationships?

Although the book’s narrative is generally more entertaining than poignant, there are moments when Debeljak does bring the reader face to face with the jolting sense of exile she sometimes felt.

One of my favorite scenes is the time when Debeljak, now pregnant, tells her husband’s family that she will not be diapering the baby Slovenian-style – na široko – which means swathed in three separate layers of diapers. (Traditional Slovenian belief holds that multi-tiered diapering is the only way to ensure that a baby’s legs will grow straight.)

Tolerant of her foreignness up until then, her in-laws finally rebel, reacting with the same kind of stunned shock her US friends and families displayed when she told them she was moving to Slovenia. Her mother-in-law bursts into tears.

Debeljak is suddenly brought face to face with her absolute aloneness. “I am going against a whole country,” she realizes. “Whatever meager knowledge of these matters I brought with me from America seems pretty unreal right now, intangible in the face of the monolithic and concrete opinion that surrounds me.”

In the end, she diapers the baby na široko.

The book closes with a few words from Debeljak on the rapid changes she has seen in Slovenia since her wedding – again, shorthand for a much larger story.

I hope someday she gives us a sequel.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.