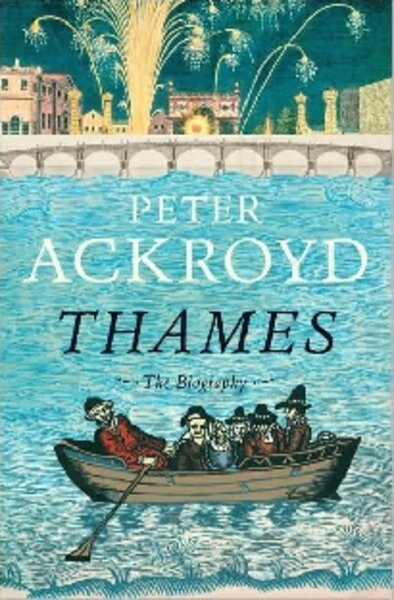

Thames: The Biography

Loading...

When Charles Dickens stood before the meandering dark of the Thames River in London, he was struck with melancholy. This was a river, “Lapping at piles and posts and iron rings, hiding strange things in the mud, running away with suicides and accidentally drowned bodies faster than a midnight funeral should,” he wrote in an essay from 1853.

“This river looks so broad and vast, so murky and silent, seems such an image of death in the midst of the great city’s life.”

The Thames is a river often overlooked in discussions of the world’s great waterways. Morose and staid, the Thames is more often linked to London’s cold and dreary weather than to its lyricism. It’s a vision that gnaws at Peter Ackroyd, the prolific British author best known for his 2000 book “London: The Biography.”

It gnaws not because Ackroyd disagrees that’s what the river once was, and not because he’s an unrepentant romantic, but because it fails to see so much of what the river actually represents. For him, the river is itself the great city’s lifeblood, and not simply an unpleasant London footnote.

In his new work, Thames: The Biography, Ackroyd sets himself the difficult task of unearthing the personality of one of the most storied rivers in the world.

More impressionistic survey than history, Ackroyd takes on a massive challenge: writing about a 215-mile-long waterway that predates human civilization and figures so prominently in British history.

This is the river that hosts the British Parliament; the river where four miles of barges followed Anne Boleyn, dressed in gold, as she traveled to her coronation; the river where Julius Caesar battled for a new chunk of empire.

He comes up with two solutions to this project, first by slicing the river’s cultural impact into distinct categories, and, second, by walking us, in 40 pages at the end of the book, village by village, from the river’s source to the sea.

We learn not of how the river directed the settlement and habitation of England but of how the river has served as a religious symbol, how it has figured into military history, and how it has been represented in song.

Ackroyd offers tender thumbnail sketches of a variety of Thames-related themes. He analyzes the history of the song “London Bridge,” investigates the etymology of the name “Thames,” and discusses the lives of the dock and boat workers who made their livings off the river.

He takes us deep into history, bringing alive distinctively British scenes of a river long ago tamed by the conveniences of modern life.

“There were soap-works and rubber-works at Isleworth, manufacturers of roll shutters at Teddington and of motor-cars at Ham. There were saw-mills in Pimlico, which became one of the centers of the timber trade. The case army of one hundred thousand workers included dockers and stevedores, lightermen and sailors, all of them owing their livelihood to the tides of the river.”

If all that sounds a little random, that’s because it is.

Majestic in scope but maddeningly short on cohesiveness, “Thames” flitters through the river’s curious past, occasionally alighting on factoids and ruminations, rather like a freshman philosophy major hopped up on sugar.

Take an excerpt from Ackroyd’s five-sentence discussion of what the existence of hermits along the river tells us about the Thames: “There was within living memory a hermit in the woods by the river at Hambleden, known only as ‘Judgment Jack.’ The river offers seclusion, and the stilling of human voices.”

We’ll leave off discussion of the chapter devoted to the connection between the river and severed heads or the one devoted to swans that begins, “Swans exist in many other places, and can be found in locations as far apart as New Zealand and Kazakhstan, but their true territory might be that of the Thames.”

But the distractions of sloppy philosophizing should not detract from the true heart of this book, when Ackroyd neglects his project of eliciting the river’s poetry and instead immerses himself in the raw power of a river whose course has shaped English history.

He doesn’t realize the emotional force of his simply bearing witness to the river until the very end, when he finds himself standing at the estuary where the river flows offshore and mixes with the vastness of the boundless sea.

Here, Ackroyd loosens his anecdotal hold of the river’s history, and is overcome. He speaks of an area in the estuary, a place used for the dumping of London’s waste called “Black Deep.”

He writes, “The estuarial marshes beside the river are liminal areas; they are neither water nor dry land. They partake of two realities, and in that sense they are blessed. That is why the Thames estuary has always been considered a place of mystery and enchantment. At times of low tide the sands and shoals become islands, with the false promise of a haven…. For many centuries this land was largely uninhabited and uninhabitable. As such it exerts a primitive and still menacing force, all the more eerie and lonely because of its proximity to the great city.”

This is not a book that anyone really needs to buy. But if you find yourself in a bookstore, and pass “Thames,” you will find it well worth your while to read the last chapter and fall under Ackroyd’s lyric sway.

Jeremy Kutner is an intern at the Monitor.