- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

- Immigration debate: New senators schooled in how work got done.

- Where urban renewal is pursued with a conservative flair

- In Costa Rica, drug-law reform that considers the bigger picture

- A year of costly natural disasters, and some signs of urban adaptation

- ‘Galentine's Day’: Why the appeal of 'ladies celebrating ladies' endures

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for February 13, 2018

Two Americans stood on the Olympics podium Tuesday: gold medal halfpipe snowboard winner Chloe Kim and Arielle Gold, the bronze medalist.

They were great. But you can make a case that it's the American in fourth place, Kelly Clark, who offers the most indelible example of Olympic ideals. Clark is a five-time Olympian and a mentor to Ms. Kim and Ms. Gold as well as other women snowboarders.

For Clark, the journey began 20 years ago, when she watched the Nagano Olympics on television. She made her Olympic debut, and won gold, in 2002 – when Kim was just 22 months old. But the path to Olympic gold can be a self-centered journey. The focus and sacrifice required to reach the global pinnacle of success almost demands it.

Yet Clark’s legacy isn’t just about inspiring the next generation of halfpipe aerialists. Perhaps her more enduring gift is nurturing a sense of purpose that goes beyond the podium or even nailing back-to-back 1080s. Since 2002, as the Monitor’s Christa Case Bryant observes, Clark herself has dramatically redefined how she thinks about success and others have followed in embracing causes beyond the slopes.

Now as the spotlight rightly shifts to the sensational 17-year-old American of Korean heritage, Clark’s wisdom shines as bright as any medal: “If your dream only involves you,” she says, “it's too small of a dream.”

Now to our five stories selected to illustrate paths to progress, including Oklahoma City urban renewal, Costa Rican justice, and security for women in India.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Immigration debate: New senators schooled in how work got done.

Stories about the US legislative process can be snoozers. But Monitor editors were intrigued by a Senate effort to break the partisan gridlock on immigration reform with an open approach that’s surprisingly retro.

The Senate may be known as the world’s greatest deliberative body. Not so in recent history. As political tribalism has grown, the minority party has often been completely shut out of the legislative process. Last year the Senate considered the lowest number of amendments in at least a decade, and fewer and fewer senators have any recollection of the days when lawmakers were routinely given the opportunity to debate and offer amendments. “Open debate in Congress is something that older senators tell younger senators they used to see. Kind of like 8-track tapes or vinyl records,” says John Pitney, a professor of political science at Claremont McKenna College. Senior senators such as Lamar Alexander (R) of Tennessee have been trying to impart some of that institutional knowledge. A bipartisan gathering called the “Common Sense Coalition” is now focused on immigration, an issue that roils both parties’ bases. Says Sen. Chris Coons (D) of Delaware: “One of the more inspiring things … has been hearing Lamar Alexander describe to us what this place looked like when it actually worked.”

Immigration debate: New senators schooled in how work got done.

Sen. Chris Coons was pumped. Heading into an unusual, free-for-all debate on immigration, the Democrat from Delaware stopped to praise the “great” open process promised by the Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell (R) of Kentucky.

“I’ve been here seven years and never seen anything like it,” Senator Coons told a scrum of reporters Monday evening. “Who knows, democracy might yet break out here on the floor of the Senate.”

After years of failing to reach an accord on an issue that roils both parties’ bases – immigration – Republicans and Democrats are trying something so old it seems radically new: looking to forge a bipartisan consensus through an open exchange of ideas.

The Senate may be known as the world’s greatest deliberative body. But in reality, the majority leader tightly controls what comes to the floor and when. In recent years, as political tribalism has grown, this has been taken to extremes – with the result that the minority party has often been completely shut out of the legislative process.

The previous majority leader, Democrat Harry Reid of Nevada, consistently blocked the ability of Republicans even to offer input on bills through amendments. Frustrated with Republicans’ blocking of executive branch nominees, former Senator Reid and the Democrats changed Senate rules so that most nominees could speed through to confirmation with only a majority vote.

When Senator McConnell took the helm in 2015, he returned to “regular order” – allowing both parties to offer changes on the floor, and for bills to bubble up through committees, rather than being cooked up in the leader’s office and handed to members as a fait accompli.

But that effort ended when the GOP won the White House. In 2017, McConnell used special rules to muscle through a Supreme Court nominee, a tax bill, and a partial repeal of the Affordable Care Act without having to get Democratic buy-in.

Last year saw a notable “demise” of debate, with the Senate considering the lowest number of amendments in more than a decade, according to John Fortier of the Bipartisan Policy Center.

The nation loses out when lawmakers are not given the opportunity to debate and offer amendments, writes Mr. Fortier in The Hill. An open process “improves the quality of legislation and deepens the legitimacy of the process by incorporating the diversity of voices and viewpoints Congress is intended to represent.”

The way things used to be

Fewer and fewer senators have any recollection of the days when the Senate routinely operated this way.

“Open debate in Congress is something that older senators tell younger senators they used to see. Kind of like 8-track tapes or vinyl records. Yes, there was such a thing once,” says John Pitney, a professor of political science at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, Calif.

Senior senators such as Lamar Alexander (R) of Tennessee have been trying to impart some of that institutional knowledge. According to Coons, the former Tennessee governor has used bipartisan gatherings of about 25 senators as a kind of tutorial on the way things used to be.

The group, called the “Common Sense Coalition,” started meeting in January in the office of Sen. Susan Collins (R) of Maine to find a way to end the government shutdown. They are now focused on immigration.

“One of the more inspiring things about the Common Sense Coalition has been hearing Lamar Alexander describe to us what this place looked like when it actually worked,” Coons told reporters. “The process of debate actually refined proposals and helped folks understand the details and hear each other and say, ‘You know, I can’t quite go for that, but maybe I could go for this.’ ”

McConnell’s offer of a fair and open process to find a fix for young, unauthorized “Dreamers,” who were brought to the United States as children, is not as altruistic as it may appear. He made the promise as part of a political deal to end the government shutdown and get a two-year budget agreement. He’s acting on that commitment.

At the same time, to pass the Senate, an immigration bill will need to clear the 60-vote threshold – and that will require Democratic support. An open process is of limited risk to McConnell, observers say, because if it fails, he can say he tried. Dreamers are not a big issue in his state, which has a low Latino population.

“I don’t see how McConnell loses, whatever the outcome,” says Ross Baker, a political science professor at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. “He personally has no dog in this fight.”

Things go wobbly

At the same time, given the free-form process – with only a shell bill and no committee-passed bill to start from – anything can happen. This can completely fall apart, with nothing able to gain 60 votes, or senators can be forced to take tough votes, such as on sanctuary cities.

Also an issue: what can pass in the GOP-controlled House and be signed by the president.

Indeed, things began to go wobbly on Tuesday, as the Senate a procedural snag as party leaders disagreed over the order of amendments. A Republican amendment backed by McConnell and reflecting the president’s priorities had not yet been set in legislative text by mid-afternoon. A bipartisan compromise by the Common Sense Coalition had yet to be struck, though senators said they were “close.”

Democrats proposed an amendment by Coons and Republican Sen. John McCain of Arizona that reflects a bipartisan bill in the House that has 27 co-sponsors from each side. The bills are narrowly focused on just two issues: Dreamers and border security.

Coons allows that his amendment probably can’t get 60 votes, but neither can the GOP bill backed by McConnell. Yet he sees them as a starting point. “They will form a core center from which we can work.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Where urban renewal is pursued with a conservative flair

You don’t often find “fiscally conservative” and “urban renewal” in the same sentence, let alone in the same city. That’s why we visited Oklahoma City for a closer look at how this successful model of progress works.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

While Republicans control a majority of governorships, relatively few sit at the helm of America’s largest cities. Yet in Oklahoma City, four-term GOP Mayor Mick Cornett has presided over a uniquely conservative – and by many measures quite successful – approach to urban renewal. OKC has turned a neighborhood of abandoned warehouses into a chic shopping and dining area, built a grand new downtown library, erected a sports arena, and wooed its very own NBA team. To pay for it all, the city raised sales taxes, through a program called the Metropolitan Area Projects Plan, or MAPS. But it has maintained a fiscally conservative approach by paying for projects as it goes, investing some $1.6 billion – all while remaining debt-free. It has also relied heavily on public-private partnerships, leading some critics to liken it to an “oligarchy.” The model has attracted interest from dozens of other cities, many of which are surprised to learn the development projects were not financed. “[Other cities] contact us probably monthly, asking about the MAPS program, and usually it gets around to, ‘How did you finance this?’ And when we tell them we didn’t finance it, they’re shocked,” says David Todd, who has headed up the city’s MAPS office for the past six years.

Where urban renewal is pursued with a conservative flair

Oklahoma’s schools, faced with a budget crunch, are increasingly going to four-day weeks. The starting salary for teachers hasn’t been raised in 10 years. The prisons are so overcrowded, they have asked for an additional $1 billion.

The state is facing an estimated $650 million budget deficit – and it’s likely to remain that way for the foreseeable future, because in this conservative state few want to raise taxes (and they can’t, without three-quarters of the legislature).

In short, there’s a big mess at the state capitol in Oklahoma City.

Across town, however, it’s a different story: The city has turned a neighborhood of abandoned warehouses into a chic shopping and dining area, built a grand new downtown library, erected a sports arena, and wooed its very own NBA team. Soon, it will break ground on a new convention center.

Remarkably, it hasn’t taken out a single loan to do any of this. No, this conservative city – the largest in the nation to vote for Donald Trump in 2016 – gave itself a facelift by bucking right-wing orthodoxy and raising sales taxes.

Now, the man who presided over much of the revitalization – four-term Republican Mayor Mick Cornett – is running for governor, and hoping to apply some of the same principles that worked at the city level to the state as a whole.

“The governor is in a position to inspire and be the champion of people,” says Mayor Cornett, speaking in an interview with the Monitor after his last State of the City address, in which he told the large audience that no city in America has come as far as his. “Health and education are two areas that this state has always had low standards for. We just allowed ourselves to not expect much,” he says. “My goal is to champion those two areas – and to raise people’s expectations.”

Politically, Cornett represents an increasingly rare breed. While Republicans control a majority of state legislatures and governorships, relatively few sit at the helm of America’s greatest engines: cities. Metropolitan areas are home to more than 85 percent of the US population and 90 percent of its gross domestic product. Yet fewer than a third of America’s largest cities today are run by Republicans. Among the top ten, only one (San Diego) has a Republican mayor.

Like many big urban centers, Oklahoma City has become less culturally conservative in recent years, says independent pollster Bill Shapard. For example, nearly two-thirds of the city’s suburban voters now support medical marijuana – something he says he never would have seen 20 to 30 years ago.

When it comes to fiscal matters, however, in some ways the city’s hand was forced. The decline of effective state government in Oklahoma – as in many states – has pushed responsibility for a whole range of projects from the capitol to city government.

“Metropolitan cities now need to do things that traditionally states did for them,” says Roy Williams, CEO of the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber, who formerly worked for the Oklahoma State Chamber. “Oklahoma is a great example…. It’s placing huge responsibility to figure out – how do you fill these voids that the state is neglecting?”

But while many cities have sought to revitalize their urban cores in recent years, Oklahoma City has done it in a unique way. Although the city has raised taxes, it has maintained a fiscally conservative approach by paying for projects as it goes – investing some $1.6 billion to burnish its image, all while remaining debt-free. It has also relied heavily on public-private partnerships, leading some critics to liken it to an “oligarchy.”

The model has attracted interest from dozens of other cities, many of whom are shocked to learn the development projects were not financed. There’s significant skepticism, however, about whether a similar strategy could be employed at the state level.

'I was skeptical'

Oklahoma City’s revitalization was born out of a failure: In 1991, it lost out to Indianapolis on a bid to attract a United Airlines facility.

As people here recall it, United basically told the city, “You guys have the best offer, but we don’t want to live here.”

So then-GOP mayor Ron Norick decided the city needed to invest in itself.

He proposed a “penny tax” – a one percentage point increase in the city’s sales tax – to raise $350 million for a round of public works projects, including the ballpark, the “Bricktown” shopping district, the library, a new sports arena, and more. The measure, known as the Metropolitan Area Projects Plan, or MAPS, passed – though just barely.

The fundamental principle behind MAPS was that the city would not put a shovel in the ground for any given project until all the money for that project was in the bank. That way, every cent would go toward building – not toward interest.

“We have people [from other cities] contact us probably monthly, asking about the MAPS program, and usually it gets around to, ‘How did you finance this?’ And when we tell them we didn’t finance it, they’re shocked,” says David Todd, who has headed up the MAPS office for the past six years.

While the funding structure was relatively unique, so was the patience required of citizens. They had to pay into MAPS coffers for more than four years before the first major project – the ballpark – was completed.

Gary Slater, for one, wasn’t a big fan.

An Oklahoma City native, he’d heard the hype a decade before around the “String of Pearls” project, which promised stables, rodeoing, and picnicking right downtown. Then all the construction stopped.

“It kind of made you wonder where the money went, honestly. So when they started talking about MAPS, I was skeptical,” says Mr. Slater, who also wasn’t a fan of the plan to close the old baseball stadium where he used to take his T-Ball team with a wad of cheap tickets from the grocery store. “But [the new stadium] really turned out nice. I ate my words.”

While Oklahoma City has a weak mayoral system – Cornett serves part-time and is reportedly paid $24,000 – the mayor has been a figurehead for the city’s success. After 14 years in office, he enjoys a 68 percent favorable rating, nearly double that of the current governor.

Skeptics say the factors that have helped revitalize the city – particularly the willingness of locals to pay a tax, because they see where their money is going – can’t be replicated from the governor’s seat.

At the state level, “It’s this battle cry where nobody wants increased taxes under any circumstances,” says Pete Brzycki, a former commercial real estate broker who now runs the independent journalism website, OKC Talk. “It’s not like [Cornett] can go on the state level and say, ‘Oh, we’ll do MAPS for Oklahoma’ – that’s not going to work.”

A land rush

Oklahoma City has always been a bit unorthodox.

Its origins can be traced back to US troops firing shots in the air at noon on April 22, 1889 – signaling the start of the Land Rush. Thousands of settlers, who had come by wagon or train, surged into western Oklahoma. By nightfall, some 10,000 people had staked out land in Oklahoma City.

Ever since, there’s been a unique culture of the public and private sectors working together, says Mr. Williams, the Chamber’s CEO, whose work has taken him all over the US as well as Asia.

“It’s pretty unusual,” he says. “I’ve lived in a lot a lot of places where … there’s just no communication, and in fact there’s animosity” between business leaders and public officials.

In what he admits is an “extremely odd” arrangement, the Chamber runs the city’s MAPS campaigns – conducting polling to see what voters want, working with the city to finalize the MAPS package, and then convincing voters to support it.

Since the original MAPS program was approved, the Chamber has persuaded voters to support a second and then a third round. In 2001, a $700 million MAPS for Kids passed by 61 percent, enabling the city to build three new high schools and renovate more than 65 existing ones. In 2008, the Chamber poured $2 million into the $777 million MAPS 3 campaign, which passed by 54 percent. There’s already talk of a MAPS 4.

Ed Shadid, a city councilman and longstanding critic of MAPS, says the Chamber’s role effectively gives business interests veto power over the elected city council members – and the ability to push through expensive projects, like the $288 million convention center, which initially polled very poorly. People were more interested, he says, in senior wellness centers, trails, and sidewalks, which cost much less, so the city bundled them together into one package.

“You put these things together with the [convention center] to get the turd in the punch bowl past the finish line,” says Dr. Shadid, a surgeon.

Serving wealthy interests over others

Shadid, a 2014 mayoral candidate, also criticizes MAPS and other city initiatives for pouring money into projects that serve the city’s wealthy – such as a downtown streetcar – rather than those who need it most, like the workers who rely on an “anemic” bus system that provides only limited services in the evenings and on Saturdays, and none at all on Sundays in this metropolitan area of more than a million people.

When it comes to diversity, there’s ample room for improvement. Cecilia Robinson-Woods, the state’s only African-American school superintendent and a member of the Citizens Advisory Board that guides the development of MAPS projects, recalls a plan to give a new green space a “Lantern City” theme commemorating the white settlers of 1889 – showing no regard for how the Land Rush sidelined Native Americans and African-Americans.

“I’m boiling…. I said, ‘Was there any thought given to making sure that there was representation from all of the people who were part of the beginning of statehood?’ ” recalls Ms. Robinson-Woods, whose mother is from the Muscogee Creek Nation. She says her concerns were initially met with bewilderment, and then she was told that the art budget, which accounts for a very small percentage of the overall project, could be used to include representation of Native Americans.

Oklahoma City also spends very little on its social services grant program, and hasn’t increased that budget in 15 years, says Dan Straughan, executive director of the Homeless Alliance since 2004. But he adds that in the buckle of the Bible Belt, with a strong commitment to social justice ministry permeating the city’s culture, officials have found “other, really creative ways” to funnel money to such services.

After the 2008 housing crash, the city got $22 million from HUD to address a mortgage crisis that Oklahoma City didn’t really experience. So the city asked HUD if they could put some of those funds instead toward the Homeless Alliance’s campus.

“To everyone’s great surprise, they said yes,” says Straughan, sitting in his office next door to the city’s shelter, which includes showers, computers, a library branch, breakfast and lunch service, and even a pet kennel with free pet food and regular veterinary visits. Straughan says homelessness was subsequently cut from 2,500 people seeking services to about half that, though it’s since risen back to about 1,400 due to rising rental prices.

Influx of entrepreneurs

Those higher rents are being driven in part by young entrepreneurs who are finding new opportunities in Oklahoma City.

Evan Anderson, a Duke University graduate and Oklahoma native, was brought home by a family tragedy but immediately saw an “abundance of opportunity.” Now he’s chief executive officer of Oseberg, a tech startup in the oil and gas industry. There’s a service-above-self mentality here, he says, and mentors who are unusually generous. One personally provided the collateral for Mr. Anderson’s company to take out a credit line; another spent hours in personal visits to help him develop his product.

Fifteen or 20 years ago, it was hard to find such folks. Just ask Renzi Stone, a basketball star at Oklahoma University who decided to stay after graduation, and founded his own company, Saxum.

“There are 10,000 of me in New York but there’s only one me here,” he realized, “and I probably can create something special.”

Today, that something special lies in a majestic old building downtown. Exit on the 5th floor and you’re greeted with tinted glass windows, and Millennials typing away in booths and cubby spaces with expansive views of the city skyline. Mr. Stone is the campaign chairman for Cornett’s gubernatorial campaign. His company, a PR firm, employs 55 people – Muslim, gay, straight, Hispanic, African-American. A third of them are first-generation college graduates.

They’re also the first occupants in the building since April 19, 1995, when Timothy McVeigh detonated a truck bomb at the Alfred P. Murrah federal building next door, killing 168 people.

The explosion was so powerful that residents 115 blocks away sitting at their kitchen table thought something had hit their home. It rattled the city, but also forged a unity that Cornett says has been crucial to its current success. For the 40-plus cities who have sent delegations to Oklahoma City to study its success in debt-free revitalization, it’s the one element that can’t be replicated.

“When people leave here,” he says, “the one thing that they have trouble emulating is that there’s a unity that’s here,” which he chalks up to having survived a major recession in the 1980s and then the bombing in 1995.

“Just like two people who go through an emotional time have a certain bond, it’s kind of like this city had a certain bond after those experiences,” Cornett says. “And that’s hard to artificially create.”

Editor's Note: The wording in the subheading has been updated to make clear that while the MAPS program has been debt-free, Oklahoma City itself is not. In addition, while the city proper has some 600,000 residents, the larger metropolitan area has more than a million; and Dr. Ed Shadid is a surgeon not an anesthesiologist.

In Costa Rica, drug-law reform that considers the bigger picture

There’s a tendency to look at crime as binary, morally right or wrong. But in Costa Rica, as in the US, some are wondering: Is the path to true justice – and a better society – really so black and white?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

The punishment should fit the crime – but what about the circumstances of the crime? In Costa Rica, almost all the smuggling of drugs into prisons is carried out by young single mothers. But many have benefited from what’s known as “77-bis”: reform to take these women’s background into consideration during sentencing, offer prison alternatives, and create a “life plan.” “It’s not the same to be poor and alone vs. poor with five kids,” one judge says. “If the reason behind the crime is distinct, why can’t the punishment be distinct?” The law is narrow – but it's opening up opportunities to rethink broader policies, advocates say, in a region where they argue hard-line anti-drug stances take a disproportionate toll on women. And less than 2 percent of beneficiaries have violated parole or wound up back behind bars. One young woman, now out of jail thanks to 77-bis, shakes her head when her progress is called a “miracle.” “A miracle is something that comes [from] nowhere, an act of God,” she says. “A lot of people have put in a lot of work to get me here.”

In Costa Rica, drug-law reform that considers the bigger picture

When Sandra was arrested for smuggling drugs into a men’s prison in 2015, she accepted it as part of the familiar cycle of her life. She’d been in and out of detention since she was 14, when she moved on to the streets, fleeing abuse at home.

But a lot has changed in the penal system since Sandra, whose last name has been omitted for privacy, first arrived at Costa Rica’s only women’s prison in the 1990s. The institution changed names, the soccer field crumbled into a river during a rough rainy season, and the prison population exploded, growing by upwards of 50 percent nationwide between 2006 and 2012.

Following Sandra’s most recent arrest, she learned of an even more profound change: her life experiences would be studied and taken into consideration during sentencing, and there were alternatives to going to jail.

The narcotics-law reform that resulted in Sandra going to rehab, getting job training, and serving three years of probation instead of years behind bars is known as 77-bis. The law is narrow – it only applies to women arrested for smuggling drugs into jails – but it’s revolutionary in a region that prioritizes hard-line punishments for drug crimes. As organized crime carves out deeper and more far-reaching paths across the Americas, most citizens and politicians are arguing for solutions that result in more people, and more time, behind bars.

In Costa Rica, drug-smuggling into prison is almost entirely carried out by women. By focusing on women like Sandra – non-violent offenders, coming from situations of poverty – 77-bis released roughly one-fifth of Costa Rica’s female prison population, essentially waving a magic wand at chronic overcrowding. But the conversation about how to reform drug laws with that cohort in mind has created broader opportunities by allowing policy-makers, public defenders, judges, and civil society to look at drug policies and punishments in a new light. That can help both men and women, and society at large, proponents hope.

“My life has always been a disaster,” says Sandra, who was introduced to crack in prison. When she was offered the opportunity of an alternate sentence under 77-bis, it required that she get sober. “I never wanted to stop using drugs before, but prison was so awful, I decided it was worth trying.” Today she’s reconnected with her siblings and grown children, is looking for work as a cook, and is 9-months sober.

“I’m alive because of this opportunity,” she says.

“Some people see this as a ‘benefit’ for people who have committed crimes,” says Cecilia Sánchez, a former minister of justice who is now the director of the Latin American Institute of the United Nations for the Prevention of Crime and Treatment of Offenders. “But, the idea that putting everyone in prison will suddenly create a safe society? We know that’s not true. It takes a lot more work than just putting people behind bars. There are questions of equality, poverty, and education.”

Outsized impact

As the population of female prisoners across Latin America blew up over the past two decades, growing on average 52 percent between 2000 and 2015, nations from Mexico to Argentina have struggled with overcrowding. Experts point to growth in the multinational drug trade, combined with few social safety nets and drug laws that barely differentiate between low-level involvement and powerful kingpins when handing down sentences. With the exception of 77-bis, drug-related offenses in Costa Rica are considered federal crimes, punishable by eight to 20 years in jail.

The region’s male prison population, by comparison, has grown roughly 20 percent. In absolute terms, they make up a far greater percentage of prisoners in Latin America. But “punitive drug policies are falling more heavily on women” across Latin America, says Coletta Youngers, a senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) who researches drug policy and has written extensively on female incarceration rates. “Jails are overflowing with women who aren’t violent and aren’t serious threats to public safety.”

Women tend to take on the high-risk, low-reward tasks of moving drugs, motivated by economic desperation, bullying or coercion by a partner or family member, or a simple lack of opportunity, studies show. In nations like Argentina, Brazil, and Costa Rica, more than 60 percent of women behind bars face drug charges. One woman who benefited from 77-bis told The Christian Science Monitor that she could make $150 each time she successfully brought drugs into a prison, trying to support her family. She’d go to multiple jails in one day delivering drugs. If she failed, she was easily replaced.

'This wasn't a quick decision'

A three-minute walk down an undulating sidewalk flanked by chain-link fence and swirls of razor wire, sits a series of concrete-block structures at the Vilma Curling Rivera women’s prison here. Inside one building, women linger in the paved courtyard, writing in journals or hanging laundry in dense rows.

Cheryl Myers fidgets on a cement bench waiting for one of the bright blue payphones. She’s served about a quarter of her 8-year sentence for selling drugs, and says she’s struggling. Her five children live an expensive four-hour trip away and they’ve only come twice so far. Many prisoners depend on family to provide food and clothes while they’re behind bars.

“Where I live, it’s really poor. It’s banana territory,” Ms. Myers says. After an injury working with bananas near her home in eastern Costa Rica, she had to look for another option. She tried cleaning homes, but only scraped together $8.50 a week.

“My kids were going hungry,” she says. “There were lots of opportunities to sell drugs. Everyone knows someone doing it. And it pays,” she adds. “I thought about it a lot, a lot…. This wasn’t a quick decision.”

When women go to jail, dependents – whether children or the elderly – are at greater risk of poverty or getting involved in criminal activity themselves. And once released, women’s criminal records tend to carry a heavier social stigma than men’s, making it tougher to break out of the cycle of poverty that often directed them toward the drug trade in the first place, Ms. Youngers, of WOLA, says.

“The traditional role for women here is taking care of the family,” says Kenly Garza, the assistant director of the Vilma Curling Rivera prison, who previously worked in men’s prisons for over a decade. “That doesn’t change once they’re behind bars,” she says.

“For women, the impact of prison is all about what’s going on outside: they call on social workers and psychologists because they’re losing sleep over their kids skipping school, worrying their children don’t have enough to eat, wondering if they’re safe and taken care of.”

One punishment, one crime

In 2010, the United Nations passed the “Bangkok Rules” for treatment of female prisoners. It called for “gender-specific options” for pretrial and sentencing alternatives that take into account “the history of victimization of many women offenders and their caretaking responsibilities.”

Costa Rica prides itself on prioritizing human rights. But that can sometimes clash with deeply conservative values. While many politicians were pushing for popular tough-on-crime responses to growing trafficking and cartel presence here, the Bangkok Rules laid the groundwork for imprisoned women’s advocates to put forth their case.

“It’s not the same to be poor and alone vs. poor with five kids,” says Roy Murillo, a judge for more than two decades. “If the reason behind the crime is distinct, why can’t the punishment be distinct?”

In 2009, a public prosecutor in the country’s north found that nearly 90 percent of all people bringing drugs into prisons here are women. Further research found that 95 percent of women in jail for trafficking drugs into prisons were single mothers, and the majority were between 18 and 35 – making the crime a more palatable place to start drug reform, observers say.

Costa Rica’s ministry of justice and public prosecutors office led an effort to encourage politicians and judges step back and look at the bigger picture.

“Things pile up, and when there are no opportunities or when someone is not educated or prepared for opportunities, that’s where social policies fail to reach, but organized crime shows up,” says Zhuyem Molina, who worked as a public prosecutor for nearly 20 years and recently began researching potential penal-code reform for the Ministry of Justice.

77-bis “was a small window [of opportunity] that’s opened many doors since,” Ms. Molina says.

For example, employment remained a central obstacle for many of the first women who benefitted from 77-bis. No matter what sentence or what type of crime, anyone who had been to jail carried a public record for at least a decade.

“When your opportunity to work [after serving a sentence] is blocked, it’s like having two punishments for one crime,” says Judge Murillo.

Controversial approach

Ms. Sánchez, as minister of justice, agreed. And not just for women. In 2017, a registry reform went into effect that eliminates criminal records for men and women who meet criteria like having non-violent crimes, and were in a “vulnerable” situation at the time. Currently, a broader sentencing-reform bill is in the national assembly.

77-bis also helped create a formal support network for women in the criminal justice system. It’s managed by the public defenders office – and by all accounts is in serious need of funding. It focuses on the factors that most often drive women toward crime in the first place. NGOs and government institutions help connect women with job training, rehabilitation services, and financial support.

But some wonder if addressing problems in terms of gender is perpetuating problematic stereotypes. 77-bis “is positive,” says Ernesto Cortés, executive director of the Costa Rican Association for the Study and Intervention of Drugs. But in some ways it plays on stereotypes, “reproducing an image of women as victims who are forced to do things.”

Claudia Palma Campos, an anthropologist at the University of Costa Rica who has conducted oral histories with female prisoners since 2008, says the reform’s narrow focus made it easier to pass, but it doesn’t go far enough.

“It’s an important law with concrete benefits, but it’s politically correct,” she says. “What [lawmakers] say is that women, due to their vulnerability, are obliged to bring drugs into prisons. What I say is that when it comes to being marginalized and affected by violence, every drug crime” is fair game, and social circumstances need to be considered for any non-violent drug crime, regardless of gender.

Making a 'miracle'?

When a woman is offered an alternate sentence under 77-bis, she, her lawyer, and a judge agree on a “life plan”: steps like enrolling in a rehabilitation program or job-skills course, as well as regular check-ins and often community service hours. Less than 2 percent of women given alternative sentences via 77-bis have violated their parole or committed a new crime that put them behind bars, Molina says, citing 2016 data from the public prosecutor’s office.

But the lives of women given alternate sentences don’t automatically transform into fairy tales. Mariana, who asked not to use her given name for her family’s privacy, is a young sex worker who isn’t behind bars thanks to 77-bis. She joins Molina for a hot chocolate near the Supreme Court on a recent afternoon. Her story has captured the hearts of a number of lawyers and social workers, but her path has been far from perfect.

Mariana was sentenced to six years of parole and 600 hours of community service. She had a rocky start, but no longer uses drugs and always asks for help when she needs it. “She hasn’t committed a crime since we started working with her,” Molina says. Prostitution is legal in Costa Rica. “It’s been hard, but she’s learned to survive in the jungle where she moves without breaking the law.”

Molina refers to Mariana numerous times as a “miracle.” Mariana visibly bristles or shakes her head and quietly whispers, “No.”

“A miracle is something that comes from nowhere, an act of God,” she says.

“A lot of people have put in a lot of work to get me here.”

Briefing

A year of costly natural disasters, and some signs of urban adaptation

The Boy Scout motto is “Be prepared.” After a record year of hurricanes and wildfires, our reporter found that some US cities are finally taking steps to be better Scouts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Natural disasters – devastating in many parts of the world – cost an estimated $306 billion in the United States alone last year. That made 2017 the country’s most expensive on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. One factor: Several of the events – including hurricanes on the Gulf Coast and wildfires in California – hit urban centers. Experts note that disaster preparedness could gain from better planning at the urban-construction stage. (Flood experts argued that in Houston, for example, the increasingly paved urban landscape prevented the ground from absorbing floodwaters.) So are big, costly disasters the new normal? Not necessarily, experts say. The relationship between climate and weather is complicated. A handful of cities are also beginning to model better practices, adding advanced drainage basins, for example, and shelters for disabled residents who can’t evacuate. “Anytime an event occurs,” says one expert, “you have a window of opportunity [because] you’ve got people’s attention.”

A year of costly natural disasters, and some signs of urban adaptation

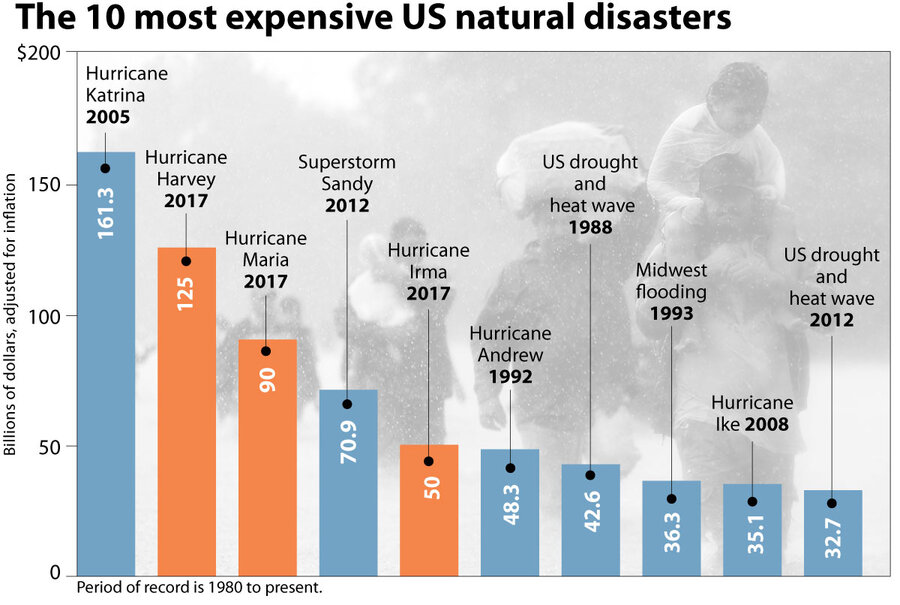

2017 was the most expensive on record for US natural disasters, according to a January report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In total, they cost the United States an estimated $306 billion.

What factors made 2017 so expensive?

Americans saw a slew of unusually powerful weather events in 2017, with three major hurricanes – Harvey, Irma, and Maria – ranking in the top five costliest natural disasters since 1980. While damage to residences represented the biggest expense, industry sustained unusually significant blows. Tourism, an economic cornerstone in the Florida Keys and many Caribbean islands, was stalled by the violent weather, and pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity in Puerto Rico was decimated by hurricane Maria. Energy production in Texas was also sharply cut in the days following hurricane Harvey’s record rains.

People were especially susceptible to last year’s natural disasters, says Susan Cutter, director of the Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. Several of the disasters – including hurricanes on the Gulf Coast and wildfires in California – hit urban centers. “The impacts are based on the exposure of populations,” she says. “Many of these events did not affect low-

density areas.”

How does the US estimate the cost of a natural disaster?

To form its estimate, NOAA draws data from public and private sources such as the Insurance Services Office, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the US Department of Agriculture. But the calculations can be messy. For one thing, the effects of a disaster are wide-ranging – everything from the destruction of houses to the lost revenue from business shutdowns. Also, many damaged assets from last year were uninsured. To correct for such gaps, NOAA scales up the data for insured losses, but it acknowledges that some costs, such as health-care related losses or values associated with loss of life, aren’t fully accounted for.

Why did some places seem ill-prepared?

“We have to make better decisions on where we allow development to occur,” says Kevin Simmons, an economics professor at Austin College in Sherman, Texas. In the US, Professor Simmons notes, tough questions about disaster preparedness rarely arise when new construction begins. Flood experts argued that in Houston, for example, the increasingly paved urban landscape prevented the ground from absorbing floodwaters.

As Professor Cutter sees it, the problem is an economic disconnect. Development in vulnerable regions is typically driven by local communities that benefit from larger tax bases and more economic activity. But when disaster strikes, it’s the federal government that often covers the damages. Local governments aren’t always held responsible for paying for the damages that risky development can cause.

Are large-scale natural disasters becoming the new normal?

“There are certain weather and climate hazards that we are seeing more often, and more severely when they see them,” says Deke Arndt, chief of the climate monitoring branch for NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. He cites increases in heat, rain, flooding, and drought.

But the relationship between climate and weather is complicated. Harsher droughts and heavier floods can lead to more extreme weather, but they don’t necessarily guarantee more disasters in the near future, according to Mr. Arndt.

In other words, think of weather as a boxer, and climate as a trainer. “Weather still throws the punches, but climate trains the boxer. And as climate changes, as you change that trainer, the boxer will throw certain punches more often and effectively,” he says.

How can communities successfully plan for future destructive events?

Experts point to a few cities with important lessons for staying safe in an uncertain future.

Tulsa, Okla., sits just above the turbulent Arkansas River, and for years it experienced devastating flooding whenever the river swelled. Three decades ago, the city decided to act. City planners built multiuse drainage basins, relocated the most vulnerable riverside residents, and imposed strict flood-minded zoning requirements for developers. The result has been fewer flooding events in the Great Plains city, says Cutter, and a stronger resolve for sustainable development.

New York City also has a new approach, after responding to superstorm Sandy in 2012 – the Rebuild by Design initiative. The program allocates federal funding to community-based solutions that emphasize disaster preparedness. Projects that New York has undertaken include transit repairs and shelters for disabled residents who can’t evacuate. The program has become a model that other cities are now following.

The most important step in achieving a sustainable recovery, says Simmons of Austin College, is generating local support. And now may be the best time to do so. “Anytime an event occurs, you have a window of opportunity when you’ve got people’s attention,” he says.

‘Galentine's Day’: Why the appeal of 'ladies celebrating ladies' endures

Many holidays celebrate family relationships or simply revolve around family. But in recent years, another holiday – spawned by a TV comedy – has emerged that spotlights the spirit of female friendship and collaboration.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Today is Galentine’s Day, a holiday invented in 2010 by the TV show “Parks and Recreation.” Eight years after an episode of the sitcom first popularized the idea, celebrations of women’s friendship are taking place across the United States on and around Feb. 13. While the cheerful main character Leslie Knope and her friends shared gifts and stories over breakfast, today’s festivities are held in museums and movie theaters, bakeries and bars – and often invite anyone, regardless of gender, to participate. Although the holiday has been propelled by commercial appeal, observers note the timeliness of an event that honors women and interpersonal connections. The competitive environment for women of five to 10 years ago has segued into one of more collaboration, they suggest. For 20-something food blogger Rachel Heffington, who has attended Galentine’s Day events at a coffeehouse in Virginia, the holiday is appealing. “I loved the spirit of it,” she says. “It was so supportive and instead of women comparing each other, we were just all there together, having fun, celebrating our friendship.”

‘Galentine's Day’: Why the appeal of 'ladies celebrating ladies' endures

Holidays made up by TV shows may come and go, but today marks one that hasn’t lost its appeal: Galentine’s Day.

“What’s Galentine’s Day?” exclaims Leslie Knope, the cheerful main character from the NBC sitcom “Parks and Recreation,” in Season 2. “Oh, it’s only the best day of the year!”

Eight years after that episode first popularized the idea, celebrations of women’s friendship are taking place across the United States on and around Feb. 13. While the bubbly Ms. Knope (played by Amy Poehler) and her friends shared gifts and stories over breakfast, today’s festivities are held in museums and movie theaters, bakeries and bars – and often invite anyone, regardless of gender, to participate.

Not unlike other holidays, Galentine’s Day has been propelled along by commercial appeal. Eateries and book publishers are among those who keep the day alive and entice celebrants. But observers and those involved in the day note that an event that honors women and interpersonal connections is timely.

“I think especially right now in the world that it’s comforting to have that camaraderie going on…,” says Kari Redman, general manager of Cure Coffeehouse in Norfolk, Va., which hosted a celebration this past weekend for the third year in a row. “They love it,” she says of customer response.

Alicia Clancy, author of the 2017 book “Be My Galentine,” about the positive aspects of women’s friendships, sees an uptick in women’s empowerment influencing the rise of Galentine’s Day. She notes that five or 10 years ago, the environment felt more competitive between women, but that as more opportunities have opened up there’s more space for collaboration.

“[F]emale friendship, the concept of ‘girl tribes,’ and empowering each other, has really picked up and taken off and I think the current political situation is probably contributing to that a bit in that women are really striving for equality right now,” says Ms. Clancy. “I think we’ve learned as a gender that we’re going to have to stick together in order to achieve that.”

Real-life celebrations dreamed up by a group of TV writers may seem odd to some. But holidays and TV have long been linked. Festivus, the anti-commercialism day celebrated Dec. 23 by “Seinfeld” fans (including Republican Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky), is still going strong. “Friendsgiving,” a Thanksgiving celebration with friends rather than family, is often attributed to another NBC sitcom, “Friends.” (But, as the researchers at Merriam-Webster discovered, the word actually has its origins elsewhere in culture.)

And look at the ubiquity of the phrase “Charlie Brown Christmas tree,” points out Daniel Gifford, an assistant professor of history at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. “The idea that, well, this came from a television show, so it’s not really real or it’s not really important, I actually don’t buy that…,” says Professor Gifford, who has taught courses including “American History through its Holidays.” “This is just another form of cultural expression.”

Galentine’s Day may have an advantage in that it lends itself more naturally to celebration than, say, the “feats of strength” portion of Festivus. Knope, on “Parks and Recreation,” explained her Galentine’s Day ritual this way: “Every Feb. 13th, my lady friends and I leave our husbands and our boyfriends at home and we just come and kick it breakfast-style. Ladies celebrating ladies. It’s like Lilith Fair, minus the angst. Plus frittatas.”

The holiday gives those who are single or not interested in a dating relationship an alternative to Valentine’s Day. To Bruce David Forbes, professor of religious studies at Morningside College in Sioux City, Iowa, and author of works including “America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories,” Galentine’s Day is similar to Thanksgiving. With Thanksgiving, the focus is on the relationship with one’s family. For Galentine’s Day, it’s on the relationships between women. In fact, Clancy says she had a yearly celebration with women friends around Valentine's Day that celebrated one another even before "Parks and Rec." They just didn't have a particular name for it.

At the Cure Coffeehouse, the festivities this past weekend included a special brunch menu based on the world of “Parks and Recreation” as well as giveaways and other diversions. For the event, the coffeehouse teamed up with For All Handkind, an organization that helps those who are new to the world of handcrafted goods, creating a “crafternoon” where patrons had the opportunity to make glass wall hangings. (Knope likely would approve: She offered her “Parks and Rec” ladies a gift bag that included handcrafted crocheted pens and mosaic portraits made from shards of bottles of their favorite diet soda.)

A few states away, Sloan*Longway, a museum and planetarium in Flint, Mich., celebrated its third Galentine’s Day on Feb 9. It welcomed patrons for an evening event that included karaoke, various shopping opportunities, and a photo booth.

“It’s just a fun night out…,” says Olivia Kushuba, the venue’s special events manager. “It’s a fun way to hang out with your friends while still getting to get pampered and shop. It’s just a unique way to spend time with your friends.”

Although Dr. Forbes says he doubts Galentine’s Day will still be celebrated in a decade, its future will likely depend on the fervor of fans. “Festivus” hit the 20-year mark last year, for example. And Gifford, in a post-interview email, explains, “[S]o many holiday traditions put a lot of work and labor onto women’s shoulders. This seems to do less of that, and may actually be popular and have longevity because of that.”

For Rachel Heffington, who attended Cure Coffeehouse’s Galentine’s Day celebration with a group the past two years, the appeal of the new holiday is simple.

“It was mostly women and we were just all having a great time with our various friends and sisters,” says the 20-something food blogger. “I loved the spirit of it. It was so supportive and instead of women comparing each other, we were just all there together, having fun, celebrating our friendship.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Bending the arc toward national service

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

A good measure of a nation’s civic health is how many people work for the public good. Another is how many opportunities are created for people to volunteer. In many Western democracies, the decline in trust of institutions – and in each other – has resulted in a drop in public service and volunteering. Recent proposals in France and Canada show ways to counter this trend. The French president has put forward the idea of mandatory national service for young people. In Canada, enrollment in a similar “service corps” is encouraged. In the United States, meanwhile, the rate of volunteering has been falling since 2005. But the US still has a wide range of private and public institutions that welcome volunteers. It still has a strong core of people who volunteer for causes. To build on that tradition, Congress set up an 11-member panel last year that has now begun seeking ways to inspire young people to serve. Encouraging young people to spend time in some sort of service can help build a solid basis for unity and progress. Each country may do it differently. But at least many are still trying.

Bending the arc toward national service

On Tuesday, French President Emmanuel Macron proposed mandatory “national service” for young people between the ages of 18 and 21. They could either join the military for a short stint or be engaged in various civic causes. The main purpose: Help France overcome its social divisions and nurture patriotism. The French military, which last saw forced conscription in 1997, might also see a boost in recruits.

In Canada, meanwhile, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced last month that he is setting up a Canada Service Corps that will encourage – not force – young people between ages 15 and 30 to volunteer. One incentive: Small grants will be given to individuals who propose worthy projects in community service.

A good measure of a nation’s civic health is how many people work for the public good. Another is how many opportunities are created for people to serve. In many Western democracies, the decline in trust of institutions – and in each other – has resulted in a drop in public service and volunteering.

The proposals in France and Canada are examples of ways to counter this trend. In the United States, meanwhile, the rate of volunteering among Americans has been falling since 2005. It went up after the terrorist attacks of 2001. And last year, a temporary wave of volunteers went into places hit by hurricanes, such as Houston and Puerto Rico. But the US still struggles to maintain the kind of public service that helps young people to bond to the nation and to others of different backgrounds. National service can provide some of the heat beneath the country’s “melting pot.”

The US still has a wide range of private and public institutions that welcome volunteers. Almost every president since John Kennedy has created an agency for public service, from the Peace Corps to Vista to AmeriCorps to Senior Corps. Yet many of the agencies do not have enough budget to welcome all volunteers. Congress keeps funding them while President Trump proposes to cut them – even though he once said there was “something beautiful” about national service. Some lawmakers have introduced bills to expand opportunities for such service.

The US still has a strong core of people who volunteer for causes. To build on that tradition, Congress set up an 11-member panel in 2017 called the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. It has just begun the work of finding ways to inspire young people to serve the country in some way. Its recommendations are due in 2020.

Civic health in a democracy comes in many forms, from voting to paying taxes to volunteering. Encouraging young people to spend time in some sort of service can help build a solid basis for unity and progress. Service to others is a reflection of a higher good. Each country may do it differently. But at least many are still trying.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

An expanded view of prayer – that heals

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Today's column includes an exploration of how prayer can – and did – bring quick and complete physical healing to a woman suffering from the flu.

An expanded view of prayer – that heals

When a friend of mine was suffering from the flu, she made a decision that might seem counterintuitive to some. Having found prayer to be effective during many other challenges, she turned to God in this situation, too.

Prayer can mean many things to different people. My friend’s approach was not to plead with God for Him to fix her material body, but to turn to God with gratitude for what she understood she had already received from God: an identity that is actually spiritual. This meant to her that she reflected God’s goodness, including the harmony that is always His nature.

This approach to prayer can seem like a big leap, but I’ve found it effective for healing. It’s based on the teachings of Christ Jesus, as explained in Christian Science, through which I’ve learned that we all are so much more than the mortal beings we appear to be. God, divine Spirit, is our creator, an entirely nonmaterial and purely good presence and power; and the creation of Spirit must naturally be spiritual also – wholly spiritual, in fact.

So when we’re facing illness or injury, it’s helpful to begin with seeking to understand God’s nature and essence. In understanding what God is, we discover our true identity. Jesus, who is recorded in the Bible as healing so many people, recognized that infinite Spirit is our only originator and that, in all ways and at all times, regardless of the material picture, our true identity remains as God’s spiritual reflection. “That which is born of the Spirit is spirit,” Jesus observed (John 3:6).

In the case of my friend, through this understanding of her spiritual nature she realized that repairing Spirit’s creation isn’t necessary, since this creation already continuously expresses God’s perfection. Her realization was more than a mental exercise. You could say that her prayer had the backing of the living God. That is, her desire to better know and understand her true, spiritual identity was impelled by God’s authority and presence, and it became clear to her that neither God nor God’s creation could have the flu or any other illness. With that, all thought of suffering left her. She quickly was free of the sickness and feeling like her regular self again.

This indicates how prayer can become to us the power of divine Truth, another name for God, working in our thoughts, helping us to recognize our real being as God knows us – spiritual and free. In one of her works, “Rudimental Divine Science,” Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy explains: “Health is the consciousness of the unreality of pain and disease; or, rather, the absolute consciousness of harmony and of nothing else” (p. 11).

When your or my prayers stem from a desire to humbly see what God has actually created and is revealing of His love and perfection, and we strive to express these qualities, there is no place left for sickness to take root in our consciousness and experience. As we acknowledge, understand, and even cherish God’s ever-presence, we gain fresh views that transform our perspective and outlook, and our beautiful, perfect, and completely spiritual identity shines forth. And this brings needed healing.

A message of love

Winter fun, not the Games

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow for the next installment of our “Reaching for Equity” series: We'll look at whether India’s new all-female police squads are the best way to improve security for women.