- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Play ball (faster)! Can innovation save Major League Baseball?

The sounds of opening day return Thursday. The smack of maple on cowhide. The cries of “Popcorn here-ah!” The eighth inning Fenway chorus of “Sweet Caroline.” These are some of the rites of a North American spring.

But when does cherished tradition become ossification, sapping vitality?

Major League Baseball faces declining ticket sales and longer games with less action. Last year, the average game lasted a record 3 hours, 11 minutes – an eternity in the Twitter age. Most folks under the age of 50 would not describe the game as America’s “national pastime.” Or to put it another way, among sports accounts on Instagram, the highest ranking baseball player, Mike Trout, comes in at No. 130.

Fortunately, MLB is displaying a willingness to tinker with the centuries-old sport – and not a moment too soon:

• In one experiment last season, minor league pitchers were limited to 15 seconds between pitches. As a result, the average game was shortened by 20 minutes.

• In another minor league test last year, the pitching mound was moved back 1 foot to give the batter more time to hit the ball.

• This year, to generate more action on the base paths, some MLB minor leagues will increase the size of second and third base (by 3 inches) and shorten the distance between the bases. An initial test last year showed this change produced more stolen bases.

Some experiments, such as “robot umpires,” are delivering more integrity. Others are a bust. But the point is the league is seeking creative solutions. As the famed New York Yankees manager Yogi Berra once said, “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

For baseball, that’s likely to be a good thing.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Life in Russia-occupied Kherson

What’s life like under Russian military occupation? Our reporter reached out to residents of one southeastern Ukrainian city who spoke with open anger and defiance.

-

Oleksandr Naselenko Special Contributor

Evidence of the cruelty the Russian military is capable of inflicting upon civilians is being revealed now in Bucha, Ukraine, northwest of the capital, Kyiv. Yet even in Kherson, near the Black Sea, where Russia may want to win over citizens to create a pro-Russian statelet, the occupation has its own brutality.

Ukrainians mounting frequent protests there have been shot at, hunted down in their homes, and kidnapped, residents say.

Aliona, a homemaker who asked that only her first name be used, describes a recent encounter with a Russian patrol whose members asked her: “How do you feel about us?” She gave them an earful.

“I told them, ‘How can I relate to you when we are lying on the floor and the neighbors’ house is being shelled? When civilians die? When a grandmother and her grandson died when you shot at their car?’” she recalls.

The son of a neighbor was recently caught at a checkpoint with videos of Russian vehicles he had posted to TikTok, she says. His captors tortured him before releasing him with a warning he would be watched.

“We worry that Kherson is not talked about in the world news, though people regularly disappear here,” says Aliona. “They interrogate people, rob people, and in every way suppress any resistance. But we hold on.”

Life in Russia-occupied Kherson

She knew it wasn’t wise to argue with Russian troops occupying her home city of Kherson, in southern Ukraine, but Aliona says she was beyond caring, angry at the arrogance, ignorance, and wanton violence she was witnessing.

When a Russian patrol stopped her in a park and asked if she could add money to their Ukrainian SIM cards – they would pay her, they said – the homemaker refused and lied, saying she could not do it.

Then the Russians asked: “How do you feel about us?”

Here the truth came out, in the first and only major city occupied by Russian forces, where Ukrainians mounting frequent protests against the Russian presence have been shot at, hunted down in their homes, and kidnapped, residents say.

Aliona, who like others in this article asked that only her first name be used, says she gave the Russian patrol an earful.

“I told them, ‘How can I relate to you when we are lying on the floor and the neighbors’ house is being shelled? When civilians die? When a grandmother and her grandson died when you shot at their car?’” she recalls.

The Russians answered: “But we told them to stop, they did not stop.”

“You just turned their car into a coffin,” Aliona says she admonished. “You didn’t even fire a warning shot.”

The cruel brutality of what the Russian military is capable of inflicting upon civilians is being revealed now in Bucha, northwest of the capital, Kyiv. There, scores if not hundreds of bodies – many with their hands tied behind their backs, and shot execution-style at close range – were left in the streets, basements, and mass graves by Russian forces as they withdrew last week, according to Western journalist eyewitnesses.

U.S. President Joe Biden has called for a war crimes case to be assembled against Russian President Vladimir Putin. Russia denies that a single civilian was harmed in Bucha, and calls reports of atrocities by its troops “fake news” staged by Ukraine.

Yet even in Kherson, 45 miles southeast of Mykolaiv near the Black Sea, where Russia may want to win over citizens to create a pro-Russian statelet called the “Kherson People’s Republic,” the occupation has been brutal, if less so than in Bucha, where streets are littered with incinerated Russian armor and evidence of abundant shelling.

Images of wholesale destruction in Bucha and further northwest in Borodyanka, as well as a host of other districts that Russian troops have now withdrawn from, are resulting in the increased departure of citizens from Kherson the past three days, says Mayor Igor Kolykhaev.

“Every single person living in Kherson and in the Kherson region cannot wait until the entire region will be freed, but ... as of now, this is surely not an easy task,” Mr. Kolykhaev told CNN Wednesday. “And obviously, given the recent news ... I can see that there is panic growing in the city of Kherson,” he said, citing the “threat of bombardment.”

Under the Russian yoke

The exchange between Aliona and the Russian troops – these soldiers were “experienced fighters with new weapons and in new uniforms, not boys” in “old Soviet helmets,” she says – illustrates the challenge of living under the Russian yoke in Ukraine.

It reveals, too, the disconnect between the occupier and the occupied, and Russian troops’ inconsistent treatment of Ukrainians in Kherson, at least, which veers from following apparent, occasional orders to “be polite,” to actions of lethal cruelty.

Residents of Kherson spoke to The Christian Science Monitor by phone even as the Ukrainian Army mounts a counter-offensive to recapture the port city of some 280,000 residents, which Ukrainian officials say faces a “humanitarian catastrophe” of food and medicine shortages due to a Russian blockade.

It is just one of several fronts where Ukrainian forces are beginning to reverse Russian gains after six weeks of war.

In her exchange with the Russian patrol, Aliona says she was “too depressed by my emotional state” to fear their reaction.

Falling back on one Moscow justification for Russia’s invasion, the soldiers said they would soon “expel the Nazis” – especially from Mykolaiv, which has so far blocked the Russian advance across southern Ukraine – and “everything will be fine.”

Aliona said she is a Kherson native, and this is the “first time I hear about Nazis.”

Then the Russians asked if she was aware that Ukraine had planned to attack Russia with biological weapons on March 1 – another unsubstantiated Moscow claim.

“I only know that, on March 1, I was going to take my child to school, and you took that from me,” Aliona replied, angrily. “You took everything from me: My friends who immigrated who knows where, the peace of mind of my child who is afraid to go to the windows ... afraid to walk down the street.”

Kidnapping campaign

Video posted online by Kherson residents shows anti-Russian street protests broken up by Russian soldiers firing live rounds, tear gas, and stun grenades. Residents describe a campaign to kidnap local activists.

“Many of us are now conducting a quiet guerrilla war,” says Aliona.

The son of a neighbor was recently caught at a checkpoint with videos of Russian vehicles he had posted to TikTok, she says. His Russian captors pulled out four teeth, all his fingernails, and broke his ribs before releasing him with a warning he would be watched.

“We worry that Kherson is not talked about in the world news, though people regularly disappear here,” says Aliona. “They interrogate people, rob people, and in every way suppress any resistance. But we hold on.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy last week disciplined two Security Service of Ukraine generals who had been in charge in the Kherson region, stripping them of their rank for “violating their oath to Ukraine.” Residents believe that was for leaking addresses of civil society activists and the families of those serving in the Ukrainian military and intelligence – lists the Russians have used in door-to-door efforts to erase anti-Russian sentiment.

That is not the only result of occupation that grates on the people of Kherson, who describe intrusive checkpoints, abductions, Russian looting of shops, and food and cash shortages.

“For us it is difficult, mentally,” says Raisa, a social worker in her mid-fifties. Especially irritating are vehicles marked with the letter “Z,” which has been adopted by Russians, on the battlefield and in their homeland, to show support for the war.

“We constantly see cars marked with ‘Z’ in the city, big and small,” says Raisa. “When they entered the city, they plundered our car dealerships and now they are driving around in new cars with ‘Z’ stickers. To say this is unpleasant is to say nothing.”

Cash is in short supply, after “our guests” – says Raisa, referring to the Russians – pulled several ATMs from walls, causing banks to stop resupplying them.

“I admire these people who go to protests because it takes courage, and courageous they are,” says Raisa, whose social work has prevented her from going. Caught near one protest, where locals regularly chant, “Kherson is Ukraine!” and “Shame on you!” she experienced herself the percussion of flash-bang grenades and the taste of tear gas.

In another incident, she says, she was stopped by a man in civilian clothes, who covered his face with a balaclava and asked her for directions to a specific address.

“They detain people and push them for cooperation ... and since our people are not in the mood for cooperation, they let them go – but some still cannot be found,” says Raisa.

“Waiting for our army”

Even if the Russian presence in Kherson has had a lighter touch than front lines near Kyiv, or in cities devastated by constant bombardment like Mariupol or Kharkiv, the occupation has upended Ukrainian lives.

“I have not yet met those people who would support Russia,” says Lena, a 30-something graphic designer in Kherson. “Many of my friends, even those who used to be pro-Russian, have now changed their point of view.

“They were infuriated by everything Ukrainian,” she says, “and said the Ukrainian language is the language of villagers. Now they hang Ukrainian flags and began to speak Ukrainian.”

Lena says she is “too emotional” about the Russian presence, and describes taking risks by swearing at and making rude gestures toward passing convoys of Russian “orcs” – an increasingly used term for Russian troops among Ukrainians, based on the evil, subhuman creatures from the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

“Everyone is very hopeful and waiting for our army to return,” says Lena. “At the same time, I sometimes meet people in lines in stores who sound like they have lost faith. They say Kherson was abandoned, but I think this is the work of Russian propaganda in order to induce panic.”

Joy has been in short supply, says Lena, as Russian troops have searched neighboring houses, and placed snipers on rooftops.

Happiness comes in glimmers, though, at news of another village “liberated” by Ukrainian soldiers, as they advance from Mykolaiv toward Kherson.

“The most joyful day will be when our forces are in the city,” says Lena. “I will meet them with flowers.”

The West has united against Putin’s war. Not Africa.

Nation-to-nation relationships are often complex. Our reporter looks at the varied motivations – ranging from historic loyalty to weapons deals – behind African support for Russia against Ukraine.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When the United Nations General Assembly voted by an overwhelming majority last month to call for an end to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, half of the 35 countries that abstained – refusing to condemn Moscow – were from Africa, and another seven African representatives did not show up for the vote.

Russia has been quietly strengthening its ties with Africa in recent years, building on residual gratitude for the help that the Soviet Union once gave to anti-colonial movements across the continent. And Moscow has found fertile ground in a number of countries in the region.

“There’s an element of supporting Russia as a counterbalance to what is seen as American hegemony or hypocrisy on a range of issues,” says a former Nigerian government adviser.

On top of that, many African rulers depend on Moscow for their weapons: Russia is the largest supplier of arms to the continent, and specializes in deals with governments that Western manufacturers boycott on human rights grounds.

Old loyalties can run deep. Linda John Selepe, a former South African freedom fighter, learned to fly military jets in the Soviet Union. More than 30 years later, he says, nothing that has happened has “changed my attitude and belief in the Russian people.”

The West has united against Putin’s war. Not Africa.

When Linda John Selepe, a 68-year-old South African veteran, first saw images of Russian aircraft flying over Ukraine, he was immediately taken back to a time when he, too, had lived with Soviet-era bomber jets roaring overhead.

In the 1980s, barely out of his teens, Mr. Selepe took up arms in the struggle to overthrow South Africa’s white-minority government, spending years in bare-bones bush camps. There, he received training, weapons, and financial support from Moscow, which supported dozens of independence movements in Africa as part of their Cold War rivalry with the West.

“The only way we could survive – the only way we did survive – was the Russian aircraft coming to bomb” enemy positions, Mr. Selepe says of his years as a guerrilla fighter operating from neighboring Angola, his voice still emotional four decades later.

“I feel pity and sympathy for the civilians of Ukraine. But I fully support Putin’s actions in Ukraine, based on my history.”

Such legacies are still playing out across the continent today, and help explain why many African states have been reluctant to publicly criticize Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.

African ambivalence was on show at a U.N. General Assembly meeting on March 2. An overwhelming majority of 141 nations voted in favor of a resolution demanding the immediate withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine. But of the 35 countries that abstained from condemning Russia, 17 were from Africa. A further seven African representatives did not record a vote at all. Eritrea, a secretive rogue state in east Africa, joined Belarus, North Korea, Syria, and Russia in voting against the resolution.

“Many African countries are sitting on the fence for a number of reasons,” says Steven Gruzd, an expert on African governance and diplomacy at the South African Institute of International Affairs. They include “not wanting to become embroiled in a new Cold War, empathy with Russia and antipathy towards the West, and diplomatic and political calculations.”

A counterbalance

U.N. General Assembly resolutions aren’t legally binding, but they do carry political weight – and the March 2 vote sent important signals about a shifting international order.

Russia has been quietly strengthening ties with African states in recent years, particularly on the military front. Military leaders from the Central African Republic, Mali, Guinea, and Sudan, among others, have invited Russian mercenaries to tackle unrest, often despite already receiving military or economic aid from the West.

The Central African Republic has said it planned to make Russian language classes compulsory for all undergraduates. Supporters of a military coup in Burkina Faso earlier this year brandished Russian flags.

And, on the day Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, South Africa’s minister of defense attended an official cocktail party at the Russian embassy celebrating Russian Motherland Defenders’ Day.

“There’s an element of supporting Russia as a counterbalance to what is seen as American hegemony or hypocrisy on a range of issues,” says a former Nigerian government adviser.

Such issues range from a lack of U.S. accountability over its invasion of Iraq to meddling in local politics, the adviser says. “America has taken on a caricature of decadence, immorality, hypocrisy, an international bully. Russia, by contrast, through savvy media manipulation, appears as the underdog.”

That view is also popular in southern Africa. “Zimbabweans have been victims of unilateral sanctions for over 20 years and would not wish this on anyone,” Zimbabwe’s foreign minister said, in a statement explaining why the country had abstained from criticizing Russia.

Guns and nukes

But some of the fence-sitting is down to hard-nosed realpolitik.

Russia’s strategy on the continent involves pursuing deals with elites, rather than states, points out Joseph Siegle, director of research at the U.S. Defense Department’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies. “By helping these often illegitimate and unpopular leaders to retain power, Russia is cementing Africa’s indebtedness to Moscow,” he notes.

And although Russia’s overall trade with Africa is minuscule, Moscow is the continent’s biggest arms supplier, in a market where Western manufacturers are constrained by human rights concerns. Russia is threatening “unfriendly countries” with sanctions, and African leaders “don’t want to cut off that access to Russian armaments,” says the Nigerian official, who asked to remain anonymous because he is not authorized to speak to the press.

Russia’s attempt to leverage the legacy of Soviet-era ties played out in a particularly unusual way in South Africa, the continent’s most developed nation.

“Russia has always seen South Africa as a gateway to expand influence in the West more broadly,” says David Fig, an environmental sociologist at the University of Cape Town who has written about Russian energy geopolitics. “One of the ways it seeks to do that is through clandestine relationships supporting [South Africa’s] energy infrastructure.”

That came to a head under Jacob Zuma, the outspoken former president who reportedly received training in the Soviet Union during the apartheid years. In 2015, Mr. Zuma attempted to sign an unconstitutional $76 billion deal with Rosatom, the nuclear power company controlled by a Kremlin oversight board, to build a number of nuclear power stations.

The proposal made no economic sense to technocrats at Rosatom, but Mr. Putin lobbied for it on geopolitical grounds, a report released by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace later concluded. Mr. Zuma himself fired three finance ministers in four days because they refused to sign off on the highly secretive pact. The deal was eventually scuppered by South African courts in April 2017.

Understanding Putin

As Ukrainian civilian casualties mount, and evidence suggesting Russian war crimes comes to light, will hesitant African states speak out more forcefully against Russia?

That is unlikely, predicts Linda Chisholm, a professor at the University of Johannesburg, who has written about how the Cold War is taught and interpreted in South Africa. “If anything, I think positions are hardening,” she says. “I think sides are chosen in terms of local politics, so positions on Russia and Ukraine become a tool in local politics to define where you stand.”

Russia is not the Soviet Union, nor does it offer any ideological message today. But among some people, such as Mr. Selepe, old loyalties die hard.

For Mr. Selepe, the former guerrilla fighter, the bombed out ruins of apartment blocks in Ukraine tell only one side of the story.

Still affectionately referred to by his guerrilla alias, “Sporo,” meaning “railway,” in Zulu, Mr. Selepe was born in 1963, at a time when the Soviet Union was almost the only country willing to offer extended support to those fighting in the anti-apartheid struggle.

Mr. Selepe spent four years in bush camps, transporting supplies to cadres, carrying out cross-border raids and escaping ambushes launched by proxy militias. In 1987, he was flown to the Soviet republic of Kirghizia, where he spent another four years learning how to fly jets in preparation for an existential battle back home.

“For me personally, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, it is Russia, and Moscow is the head,” Mr. Selepe says. “Whatever happened with all these countries that got their independence, it didn’t change my attitude and belief in the Russian people.”

Shortly after he returned to Africa, apartheid collapsed, in 1994. Mr. Selepe was integrated into a South African air force that was racially mixed for the first time. His training abroad, he says, meant he had more knowledge and skills than many of the white officers who had once been his sworn enemies.

Almost every Sunday morning since the war broke out, Mr. Selepe has left his home in a tidy Johannesburg suburb, turned a corner, then walked a few hundred yards until he reaches a gold-domed Russian Orthodox church. There, he says, he nods along to the liturgy, delivered entirely in Russian, and offers prayers for both Russian and Ukrainian citizens.

Returning home, he settles down to watch the relentless news from Ukraine. “When Putin is speaking on television,” he says, “I don’t read the captions. I just follow what he’s saying. I understand all of it.”

Monitor Breakfast

Biden adviser: Sanctions on Russia are getting tougher

How is the U.S. economy doing? How about sanctions on Russia? We get the perspective of the director of the White House National Economic Council, who shared his views at the Monitor Breakfast Wednesday.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Sometimes, it seems, Americans are living in two economies. There’s the one that’s undergoing an extraordinary recovery from the pandemic shock, with 11 straight months of job gains topping 400,000, unemployment down to 3.6%, and rising wages.

Then there’s the economy of high energy costs and 7.9% overall inflation, a 40-year high affecting everyday staples.

Asked about this, and polls showing President Joe Biden getting little credit for the positives, Brian Deese, director of the White House National Economic Council, acknowledges the frustration.

But he quickly follows up: “Our view is not, the economy’s great, why isn’t anybody noticing? It’s that we need to recognize and build on the uniquely strong aspects of this economic recovery in addressing the clear, ongoing challenges, particularly around inflation and costs for families.”

Mr. Deese also discussed new sanctions on Russia announced Wednesday by the Biden administration with other Western economies. He advised “patience and perspective” in allowing the sanctions to take effect.

“Anyone who looks at the Russian economy right now and thinks they’re bouncing back or showing some signs of life is I think missing the forest for the trees,” Mr. Deese said, citing forecasts that Russia’s economy will contract by 10% to 15% this year.

Biden adviser: Sanctions on Russia are getting tougher

Sometimes, it seems, Americans are living in two economies. There’s the one that’s undergoing an extraordinary recovery from the pandemic shock, with 11 straight months of job gains topping 400,000, unemployment down to 3.6%, and rising wages.

Then there’s the economy of high energy costs and 7.9% overall inflation, a 40-year-high, affecting everyday staples such as food and household items.

Polls show President Joe Biden gets little credit for the positives – some voters even deny any job gains – and plenty of blame for the negatives. On top of that, the November midterm elections are fast approaching. Ask the president’s top economic policy adviser, Brian Deese, whether there’s a sense of frustration, and he chuckles ruefully.

“I’ll hesitate to provide commentary on my feelings,” said Mr. Deese, director of the White House National Economic Council, at a breakfast for reporters hosted Wednesday by The Christian Science Monitor.

But he quickly follows up with a serious response, calling this dichotomy of public perception a “false debate.”

“Our view is not, ‘The economy’s great; why isn’t anybody noticing?’” Mr. Deese says. “It’s that we need to recognize and build on the uniquely strong aspects of this economic recovery in addressing the clear, ongoing challenges, particularly around inflation and costs for families.”

Mr. Deese also addressed new sanctions on Russia related to its invasion of Ukraine, announced Wednesday by the Biden administration in conjunction with the Group of Seven top industrialized Western economies and the European Union. The sanctions target two of the country’s largest banks, Sberbank and Alfa Bank; several state-owned Russian enterprises, including an aircraft and shipbuilding corporation; the adult daughters of President Vladimir Putin; and family members of Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. Also included is a ban on inbound investment by Americans in Russia.

The key to effective sanctions, Mr. Deese said, is international coordination. He advised “patience and perspective” in allowing the sanctions to take effect.

“Anyone who looks at the Russian economy right now and thinks they’re bouncing back or showing some signs of life is I think missing the forest for the trees,” Mr. Deese said, describing Russia as “completely ostracized.”

He said the Russian currency, the ruble, is rebounding principally as a function of the “contorted capital control regime that the Russian Central Bank or the Russian government are having to put in place, which is in and of itself bleeding them of resources.”

He added, “Most estimates are the Russian economy is now on track to contract by 10% to 15% over the course of this year, which would be historic and on the order of what they experienced in 1998.”

At the Monitor Breakfast, Mr. Deese also discussed the shortage of semiconductors in the United States, the long-term economic challenge from China, energy production, and climate change. The audio of our session is available here.

Following are additional excerpts of Mr. Deese’s comments, lightly edited for clarity.

On the impact of the U.S. shortage of semiconductors, essential for the electronics behind everything from cars to smartphones:

The best estimates are that the lack of available semiconductors probably took a full percentage point off of GDP in 2021.

Today we produce 12% of global semiconductors in the United States. But we produce none of the advanced leading-edge semiconductors. So we are 100% vulnerable on foreign supply chains for those advanced semiconductors. And what we are seeing is increasingly aggressive efforts by China and other countries to try to build their own resilience in semiconductor manufacturing, which, if not addressed effectively by the United States, would increase our vulnerability and our economic risk.

On geopolitical tensions, particularly between China and Taiwan, accelerating the need for “reshoring” initiatives to bolster manufacturing in the U.S.:

Ten, 11 months ago, I went out and explained a core part of President Biden’s economic strategy as having an affirmative industrial strategy for the country. And at the time, the question was, is, that actually, why should we have an industrial strategy? Does that bring up echoes of failed industrial policy in the past?

And I would say over the course of the last 10, 11 months, that question has now gone decidedly from why to how – that the debate around, do we need to be more deliberate and explicit and have more direct and proactive public investment and public-private partnership to build industrial strength in key sectors of our economy, is now much more broadly understood and a broadly shared goal across the aisle, Republicans and Democrats.

On the apparent lack of increased energy production in the U.S.:

We’ve been having conversations with oil and gas producers. ... Our takeaway from the data is that in the immediate term – over the next, call it, six to 12 months – there is no constraint to companies ramping up production. And the price in the market environment provides a lot of reason and rationale for them to do so.

A number of companies have now explicitly made decisions, are increasing “cap ex” [capital expenditures], and the result of that is why we’ve now seen projections of U.S. domestic production increase, such that by the third quarter of this year, the expectation is we’ll be up by about a million barrels a day.

That is the result of people responding to market forces.

On the Biden administration’s year-two strategy on private-sector engagement on climate change:

The war in Ukraine and the geopolitical consequences of energy that we are seeing play out now really do provide as stark a reminder as anything of the need to accelerate our transition to ultimate energy independence, which ultimately means reducing and eliminating our dependence on fossil fuels altogether.

That is a process that will only happen if the American private sector, including the incumbent energy producers in the United States, utilities and otherwise, are an inextricable part of that process. And that’s defined our approach from the get-go.

For example, the clean energy tax-credit package that we have been working on is designed explicitly with the understanding that what we will do on the government side is provide long-term technology-neutral incentives that the private sector then will drive and innovate off.

Does rape within marriage count? To India’s courts, no.

India is one of the few countries that doesn’t recognize marital rape as a crime. Our reporter looks at how women are doggedly pursuing justice on this issue.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Sarita Santoshini Contributor

In one of Mumbai’s sprawling informal settlements, Amina faced emotional, physical, and sexual abuse from her spouse for nearly 20 years. “I always felt like what was happening to me was wrong,” says Amina, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, “but then I’d think, he’s my husband.”

Although Indian women are 17 times more likely to experience sexual violence from their own husband than anyone else, India remains one of the few democratic countries that doesn’t consider nonconsensual sex within marriage to be rape.

A two-judge bench of the Delhi high court is currently mulling over petitions to strike down the marital rape exception. Judgment was reserved in late February, and a verdict could come any day. Many, including the government, have argued that expanding the definition of rape “may destabilize the institution of marriage.” It is this view, petitioners and experts say, that shrouds the issue in shame and keeps women from seeking support.

The country’s rape laws stem from “patriarchal thinking that once a woman is married, she has no agency,” says Mariam Dhawale, general secretary of All India Democratic Women’s Association, adding that closing the marital rape loophole “opens up a door for women to ask for justice.”

Does rape within marriage count? To India’s courts, no.

In Mumbai’s informal settlement of Dharavi, women know they can turn to Amina. As a volunteer with the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA), a nonprofit that works on issues of women’s health and safety, she’s always out and about, checking in with women in her neighborhood and supporting those facing violence at home. She urges them to call the police help line or visit the crisis center, but as a survivor herself, she understands why many don’t.

For almost 20 years, Amina – whose name has been changed to protect her identity – faced relentless abuse from her husband. He controlled her movements and finances. If she were even 10 minutes late dropping their children off at school, she was beaten and locked outside their home. Her neighbors knew about some of the abuse, but what they couldn’t know, she says, was that “he forced himself on” her as well. At the time, Amina didn’t even understand that this was rape. “I always felt like what was happening to me was wrong, but then I’d think, he’s my husband,” Amina says about the sexual violence. “Even today, things are the same way. Women can’t easily open up about it.”

One in 3 Indian women between the ages of 18 and 59 say they’ve experienced some form of spousal violence, according to government data, and further analysis shows Indian women are 17 times more likely to experience sexual violence from their own husband than anyone else. Yet India remains one of the few democratic countries that doesn’t consider nonconsensual sex within marriage to be rape.

A two-judge bench of the Delhi high court is currently mulling over petitions to strike down the marital rape exception. But many, including government representatives, argue that expanding the definition of rape is antithetical to the institution of marriage in India. It is this view, petitioners and experts say, that shrouds the issue in shame and keeps women from seeking support.

“We have seen that the husband uses sexual violence as a means to exert power over his wife,” says Mariam Dhawale, general secretary of All India Democratic Women’s Association, one of the petitioners. She attributes this behavior to a “patriarchal thinking that once a woman is married, she has no agency, she has no right to refuse her husband.”

Judgment was reserved in late February, and a verdict is expected any day. Yet no matter what the court decides, advocates say the road to justice will be long.

Legal and cultural battles

In India, the push to criminalize marital rape goes back decades. In 1983, following the rise of a women’s movement set on tackling India’s complacency toward sexual violence, lawmakers amended India’s rape laws for the first time in 100 years. Victories included amendments acknowledging custodial rape and rape by authority figures, and new measures to protect survivors’ identities. India also established a section of law against cruelty by husbands and husband’s relatives, including dowry-related harassment. But they weren’t able to close the marital rape loophole.

In 2013, following the brutal rape of a young woman in the capital, New Delhi, a committee instituted by the government to reassess sexual assault laws recommended the marital rape exception be removed. Yet Indian parliamentarians did not act on the recommendation.

“How can an offense not be an offense only because the perpetrator is different?” asks Saumya Uma, law professor and director of the Centre for Women’s Rights at Jindal Global Law School, via email. “In the face of fundamental right to life, dignity, privacy, and equality, the marital rape exemption is bad in law and must go.”

The case currently before the high court dates back to 2015, and in a 2017 affidavit, the government strongly opposed the petitions, stating that “what may appear to be marital rape to an individual wife may not appear so to others.” It also held that removing the exception “may destabilize the institution of marriage” and would offer women “an easy tool for harassing the husbands.”

Hearings held earlier this year caused an uproar among self-described men’s rights activists, who called for a marriage strike on Twitter. They also echoed the government’s concerns about wives filing false cases, fears that do not match the reality on the ground.

In fact, both data and experts highlight that most cases of domestic violence, especially sexual abuse, go unreported.

This is in part due to powerful cultural norms about women’s role within families. At their wedding, many women are told to maintain the family’s pride and conceal its shame, says Renu Mishra, executive director of the Lucknow-based nonprofit Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives Trust. In India, where only 20% of women are part of the labor force and an even smaller percentage own land or property, lack of economic independence also plays a huge role in married women not reporting sexual violence, she adds. Ms. Mishra says she has seen firsthand that most laws meant to prevent gender-based violence are seldom effectively implemented because the society and justice system continue to be patriarchal.

Those who do report domestic violence are likely to encounter apathy from police or harassment from their husband or family members, says Nayreen Daruwalla, program director of prevention of violence against women and children at SNEHA. “The change has to be systemic,” she says.

Path forward

In the face of rape and violence, Indian wives have few options. In a country with a divorce rate of 1.1%, most women feel unable to walk out of an abusive marriage. In 2016, over one-third of global female deaths by suicide were Indian women, with married women making up the largest proportion.

In Mahoba district of Uttar Pradesh, Usha Agrawal, a caseworker for Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives Trust, has counseled many women dealing with domestic abuse. She says the violence often starts with wives refusing to fulfill husbands’ demands in the bedroom, and even after years of abuse, many feel they’d have nowhere to turn if they filed a complaint. “They struggle to arrive at a decision quickly, and end up bearing this kind of violence and torture every day,” she says.

This is what happened with Amina, who today regrets not walking away from her marriage earlier or seeing her legal case through. She lives alone with her children now. “Generations are passing by; so many years have been lost. But women are still facing the same difficulties,” she says. “The afflicted are still afflicted.”

The path forward requires vast social, cultural, and legal change, but there is reason for hope, experts say. Despite barriers, data shows that some women do report violence at home – nationally, about 30% of the cases categorized as crime against women in 2020 were registered under “cruelty by husband or his relatives.”

That’s at least in part due to advocates like Ms. Agrawal and Amina offering women the language and resources to confront what’s happening to them. Moving forward, experts say, India must acknowledge that all women are entitled to full bodily autonomy – regardless of their marital status – and they agree that striking out the marital rape exception would be a step in the right direction.

“It opens up a door for women to ask for justice,” says Ms. Dhawale of the All India Democratic Women’s Association.

Essay

I have two adopted sons: One Russian, one Ukrainian

A moving, personal essay that confirms there’s no natural enmity between people at war. And this father’s sons are proof of it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Robert Klose Contributor

As I watch tragic scenes in Ukraine, I cannot help reflecting on the light they throw on my family. I am the father of two adopted boys, one from Russia and the other from Ukraine.

Young men now, they still carry a strong sense of their origins, although Alyosha less so than Anton. Where Alyosha regards Russia almost academically, Anton’s feelings for Ukraine run deep.

When the war began, elder brother Alyosha reached out to Anton. They spoke on the phone for a good hour. Afterward, Anton seemed less beset, more collected after the brotherly embrace.

I’m grateful that the war has not altered my sons’ fraternal sensibilities. I am grateful they are here with me in a land at peace.

I shudder when I consider that my sons might be fighting each other, had they stayed. But they’re not. They are here, and they’re safe.

In this age, when it is easy to take sides, events have instead pushed my sons closer together. Alyosha and Anton talk like the brothers they are. I am not looking at a Russian and a Ukrainian; I am looking at two people who love each other.

I have two adopted sons: One Russian, one Ukrainian

As I watch the tragic scenes in Ukraine unfold, day by day, I cannot help being mindful of the light this has thrown on my unique family situation. You see, I am the father of two adopted boys, one from Russia and the other from Ukraine.

Young men now, each making his way in life, they still carry a strong sense of their origins, although Alyosha less so than Anton. Where Alyosha regards Russia almost academically, and does not often think about the land of his birth, Anton’s feelings for Ukraine run deep: When Russia invaded Crimea in 2014, Anton was 17. He wrapped himself in a Ukrainian flag and trudged to school through the snow.

When the current conflagration began, Alyosha, as the older brother, reached out to Anton. They spoke on the phone for a good hour. I don’t know what exactly was said, but when Anton came away from the call, he seemed less beset, more collected from the brotherly embrace. Whatever Alyosha said, his words had tempered Anton’s emotions.

I am grateful. I’m grateful that the war has not altered my sons’ fraternal sensibilities, and that they behave as though their bond is one of blood, rather than circumstance. And not least, I am grateful that they are here with me in a land at peace, where they can step outside with every expectation of making it through the day unharmed.

These are not small graces, and if I have learned anything lately, it is to not take these things for granted.

But beyond gratitude, another word comes to mind: absence. Let me explain.

I recall, when Alyosha was 10, watching the TV news with him. It was the height of the war in Chechnya, and the scenes of devastation were heartbreaking. Alyosha was old enough to understand the situation. As we watched, he drew close to me and said, “Dad, I’m so happy you got me out of there.”

Alyosha isn’t from Chechnya, but he was making a broader statement about his sense of security and well-being: I am not there, I’m here, and I am safe.

I see dense gatherings of Ukrainian mothers and children, huddled in dark, vulnerable spaces on the news now. But my boys aren’t there. They’re here.

I see children crying as they cling to fathers who must separate themselves to defend their soil. But my sons are here, and I am available to them.

Most chillingly, when I see Russian and Ukrainian soldiers doing battle, I shudder when I consider that, had my sons stayed in their birth countries, they might be fighting each other. But they’re not. They are here, and they’re safe.

My sons’ well-being, their good fortune, was not entirely my doing. I owe a great deal to my family and friends, who supported my adoption efforts, as well as the many dear Russians and Ukrainians who labored so enthusiastically, competently, and empathetically on my behalf, so that I could take two little boys across a vast expanse of ocean and give them their hearts’ desire: a family.

And so, in these troubled times, when it is easy to draw battle lines and take sides, events have, instead, pushed my sons closer together. I hear Alyosha and Anton talking like the brothers they are, showing concern for each other, and I realize that I am not looking at a Russian and a Ukrainian; I am looking at two people who so love each other that doing the other harm is unthinkable.

From what I see of the news, there are many others like them, striving, in Abraham Lincoln’s hallowed words, to honor the better angels of their nature.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why this UN climate report is different

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The latest United Nations climate report, released Monday at some 3,000 pages, came with at least one surprise. It agreed with a few big oil exporters that the goal of halting global heating will require the capture of carbon pollutants and either burying or reusing them. Carbon removal for certain “hard-to-abate” uses of fossil fuels is “unavoidable” to achieve net-zero emissions, the report stated.

This shift reflects more than recent advances in carbon removal technologies or a rapid increase of investments in them over the past five years. It also represents a more mature listening by policymakers to weigh the arguments of those offering alternative pathways to curb climate change. Environmental groups have long been divided over whether to work with those seen as destroying nature. Treat them as enemies or potential collaborators?

Since its founding in 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has steadily perfected the art of negotiating its policy recommendations, based on both scientific advice and inclusive deliberation. That has required less shaming and demonizing while learning to listen with respect and even empathy to others.

Both urgency and understanding are needed to meet difficult climate goals.

Why this UN climate report is different

The latest United Nations climate report, released Monday at some 3,000 pages, came with at least one surprise. It agreed with a few big oil exporters, such as Saudi Arabia, that the goal of halting global heating will require the capture of carbon pollutants and either burying or reusing them. Carbon removal for certain “hard-to-abate” uses of fossil fuels is “unavoidable” and “essential” to achieve net-zero emissions, the report stated.

This shift by the U.N. panel reflects more than recent advances in carbon removal technologies or a rapid increase of investments in them over the past five years. It also represents a more mature listening by policymakers to weigh the arguments of those offering alternative pathways to curb climate change.

Environmental groups have long been divided over whether to work with those seen as destroying nature. Treat them as enemies or potential collaborators? Are your opponents open to new ideas and compromise, or are they set to win?

Since its founding in 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has steadily perfected the art of negotiating its policy recommendations, based on both scientific advice and inclusive deliberation. That has required less shaming and demonizing while learning to listen with respect and even empathy to others. One of the IPCC’s most contentious issues is whether endorsing technologies that might quickly fix global warming would lessen the drive to end the use of fossil fuels.

The report takes a cautious approach to that argument, emphasizing that carbon capture is not yet commercially viable or at a scale to greatly reduce atmosphere warming. Nations must still cut oil and gas use by 60% to 70% by 2050. Yet it also accepts arguments that certain products made only from petroleum, such as plastics, might be needed in the far future, or that many underdeveloped countries may be slow to end their reliance on oil.

The report reflects a shift toward “carbon management” rather than decarbonizing the world economy. Much of Europe and North America, as well as Saudi Arabia, are already investing in carbon removal technologies. While these methods are still not yet as feasible a solution to global warming as renewable sources of energy, the U.N. panel’s serious consideration of them shows a better convergence of thinking on how to deal with climate change. Both urgency and understanding are needed to meet difficult climate goals.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Resting – in action!

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Recognizing our spiritual nature as restfully coexistent with God at all times enables us to overcome limitations associated with “insufficient” sleep.

Resting – in action!

When I was growing up, my parents regularly asked, “Did you sleep well?” They simply meant, “Do you feel rested?”

Nowadays, it’s more complicated. For many people, their response would depend on “sleep duration,” “sleep quality,” “sleep phases,” “environmental factors,” and “lifestyle factors.” And the inquirer tends to be a smart device!

That key measurement, “Do I feel rested?” can get lost in the flood of information, as a colleague’s friend found out. She often woke up feeling great, until her sleep tracker app brought her down by informing her that she hadn’t slept well. Finally, she realized she didn’t need this second opinion. She ditched the tracker and has felt better ever since.

Wanting to sleep well is a legitimate desire that predates our digital era, going back to biblical times and the promise that our “sleep shall be sweet” (Proverbs 3:24). But having a restful night is less about understanding sleep and more about grasping that, as God’s unique expression, we have a spiritual nature that “restfully coexists” at all times with God. So, being rested is a natural outcome of living according to this spiritual nature.

That doesn’t deny the value of “a good night’s sleep,” but rather points to a higher means of gaining the rest we seek – a means that is always at hand. You could call it an active rest. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” written by Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science, describes it this way: “The highest and sweetest rest, even from a human standpoint, is in holy work” (pp. 519-520).

I’ve found that this restful work ranges from silent, healing prayer to whatever roles we feel led to take on by listening for and acting on direction from the law of Love, God. Feeling rested in these activities changes the way we think about sleep. It diminishes the sense of being beholden to material rules believed to define our rest. Instead, we increasingly realize that there are spiritual rules that overrule the penalties commonly believed to be associated with failing to follow sleep health laws.

Here’s one of those spiritual rules: “Whatever it is your duty to do, you can do without harm to yourself” (Science and Health, p. 385). Jesus proved this in ways that were sometimes remarkable and sometimes simple, including in regard to sleep. Following a night awake in the holy work of communing with God, he was energized, not weary. He appointed his chosen apostles, healed “a great multitude of people,” and delivered a sermon of spiritual guidance that has stood the test of time (see Luke 6:12-49).

When called to do so, we too can perform duties that limit our sleep “without harm” to ourselves – whether completing a deadlined project, nursing a newborn or someone who’s sick, or responding to an urgent request for healing prayer. This isn’t about powering through on the promised adrenaline of human will, but about letting that communing with God open our thoughts to a profound peace that’s always inherent in us as God’s offspring.

This involves accepting that we reflect the ever-active yet ever-restful divine Mind, God. To the extent that we become conscious of this freedom from material expectations, we find that it unveils an inherent strength and energy that are independent of repose or recuperation. This not only energizes us if we get less sleep than usual, but also lessens the attention we give to sleep generally. It can even lessen what we feel is the “usual” amount of sleep that we need (see Science and Health, p. 128).

That’s not to say we need to learn this lesson every night for the rest of our lives! But it does mean our right to feel rested isn’t conditional on material data, however gathered. Paying less attention to how we have slept, and more attention to what we are as God’s child, we increasingly find rest in the action of prayerfully understanding and lovingly expressing this spiritual identity.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Jan. 10, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

For a regularly updated collection of insights relating to the war in Ukraine from the Christian Science Perspective column, click here.

A message of love

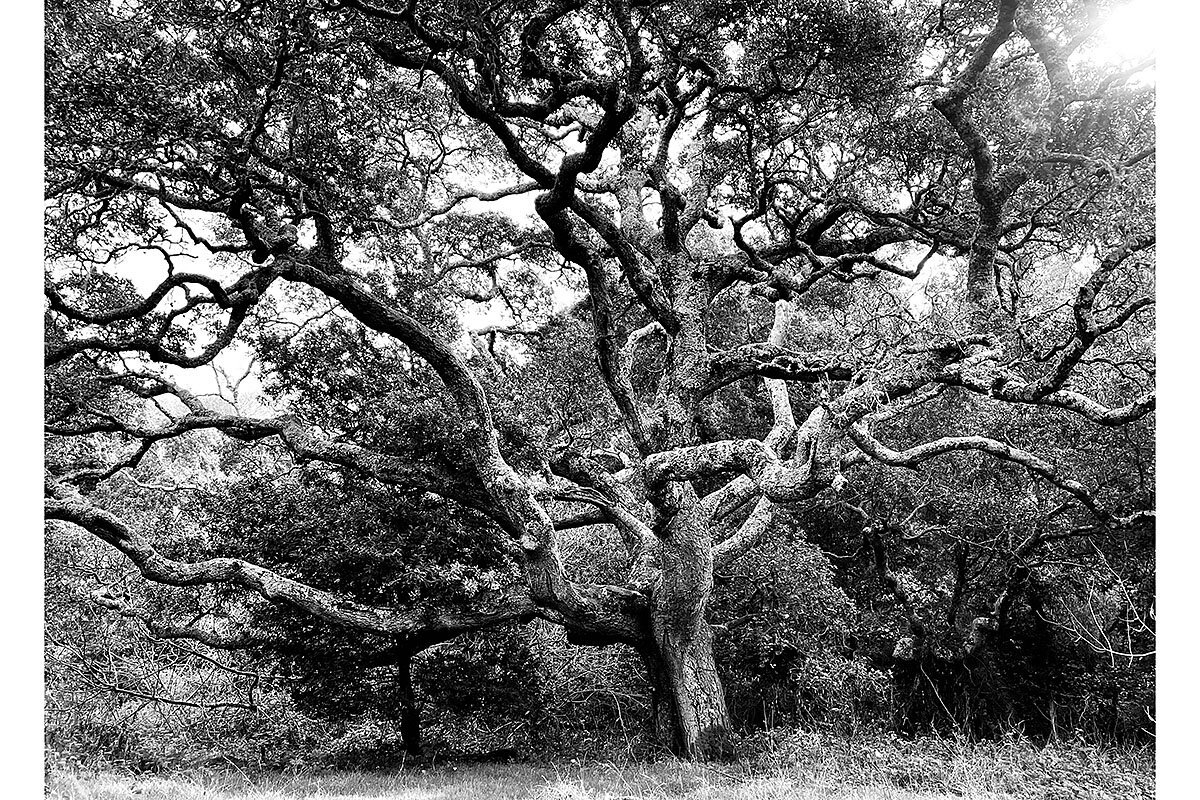

Images that sing without color

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about the return of near-extinct Navajo-Churro sheep, which signals a cultural and economic revival too.