- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

In search of confidence

Confidence is a pillar of a well-functioning society – a point powerfully underscored when it starts to crack.

Two stories today drive at the foundational importance of “full trust,” as confidence can be defined. One involves business: The Boeing Co. is scrambling to reassure the public after a series of safety violations that spoke to ethical shortcomings. Another gets at the social fiber that frays when people are forcibly denied a place in their society – and their sense of their value to it.

But both stories also point to the power of prioritizing efforts to regain trust. As one source told staff writer Laurent Belsie, it’s the “grease” that bolsters positive relationships across society.

You can check out more of our ongoing project about trust here: Rebuilding Trust.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The president, Congress, and responsibility for US border

With a border security bill looking unlikely to pass, experts say the president can take some steps to stem a surge in crossings. But big policy changes – and funding for them – must come from lawmakers.

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

-

Caitlin Babcock Staff writer

President Joe Biden and congressional Republicans agree there is a “crisis” at the southern border.

But they disagree on whether the president has the authority to make substantial policy changes alone – or must wait on Congress for more sweeping reforms and the funding to enact them.

Mr. Biden has urged Congress to pass the bipartisan Senate deal released this weekend, saying it would give him new emergency authority to “shut down” the border – authority he has pledged to use immediately. His vow, in effect acknowledging a failure to adequately control a migrant surge under his watch but putting the onus on Congress to act, has sparked a broader debate about how much executive authority Mr. Biden already possesses to secure the border.

Now that question has taken on greater urgency. With the Senate deal looking increasingly unlikely to pass, executive authority may end up being Mr. Biden’s only option.

The debate goes to the balance of power between two of America’s three branches of government, and raises the question of who is ultimately accountable for securing the border. That’s not only a policy question but also a political one, with one recent poll showing that immigration is now voters’ No. 1 concern heading into the 2024 presidential election.

The president, Congress, and responsibility for US border

President Joe Biden and congressional Republicans agree there is a “crisis” at the southern border.

But they disagree on whether the president has the authority to make substantial policy changes alone – or must wait on Congress for more sweeping reforms and the funding to enact them.

Mr. Biden has urged Congress to pass the bipartisan Senate deal released this weekend, saying it would give him new emergency authority to “shut down” the border – authority he has pledged to use immediately. His vow, in effect acknowledging a failure to adequately control a migrant surge under his watch but putting the onus on Congress to act, has sparked a broader debate about how much executive authority Mr. Biden already possesses to secure the border.

Now that question has taken on greater urgency. With the Senate deal looking increasingly unlikely to pass, executive authority may end up being Mr. Biden’s only option.

The debate goes to the balance of power between two of America’s three branches of government, and raises the question of who is ultimately accountable for securing the border. That’s not only a policy question but also a political one, with one recent poll showing that immigration is now voters’ No. 1 concern heading into the 2024 presidential election.

Mr. Biden’s likely rival, former President Donald Trump, issued 472 executive orders on border and immigration policies according to a 2022 report from the Migration Policy Institute, which supporters credit with keeping illegal crossings to an average of half a million per year. Among other things, the Trump administration required 70,000 migrants to await far-off court dates outside the United States through his “Remain in Mexico” initiative, revived a Clinton-era provision that fined unauthorized immigrants up to $813 per day if they didn’t comply with an order to leave the country, and – once the pandemic hit – invoked a 1944 law to expel migrants on public health grounds.

Mr. Biden, who campaigned on promises of instituting a more humane and comprehensive approach to fixing America’s broken immigration system, reversed many of those policies through executive action that at least initially outpaced Mr. Trump. On his first day in office, Mr. Biden terminated the national emergency at the southern border, and with it the construction of a border wall – and sent Congress a comprehensive immigration reform bill that the Migration Policy Institute characterized as the most ambitious in a generation.

But in the three years since, Congress has so far failed to pass such legislation. Meanwhile, the average number of annual crossings has quadrupled to more than 2 million, though that number reflects in part a higher rate of repeat attempts by migrants expelled on public health grounds. This fall the Biden administration announced plans to restart construction on a portion of Mr. Trump’s border wall, and the president asked Congress for $13.6 billion to address the crisis.

Republicans say if Mr. Biden would just avail himself of the powers already at his disposal, the bulk of the illegal crossings could be stopped virtually overnight. In a rebuke of what they call irresponsible Biden administration policies, GOP House members were expected to hold a vote today on impeaching Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. Speaker Mike Johnson has compiled a list of 64 executive actions the Biden administration has taken that Republicans say undermined border security and encouraged illegal immigration.

“Without any congressional action, Biden could fix this crisis,” says Mark Morgan, who served as acting commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection in the latter part of the Trump administration. “With that same pen that he used to stop [Mr. Trump’s] policies, he could reinstitute them.”

But while Mr. Trump’s policies were depicted by supporters and critics alike as some of the most restrictive in history, they did not shut down the border. Though illegal crossings dropped significantly as the president set a tough tone in his first year in office, they increased substantially later in his tenure before he implemented additional policies. Those included expedited deportations and a deal with Guatemala to limit asylum-seekers in July 2019, after which the numbers dropped precipitously.

At the same time, courts overturned some of Mr. Trump’s policies. And there were still significant gaps: The wall he promised to build was not completed, the border remained porous, and immigration courts were backlogged. Democrats say Mr. Trump’s actions were not nearly as effective as he and his allies claimed, and add that the policies presented a threat of a different kind to America.

America will survive as a nation only if “we live up to our basic values of fairness and justice and treating people well,” says Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy, calling Remain in Mexico a “deeply inhumane” policy. Rights groups say migrants were subject to kidnapping, assault, and other dangers while awaiting word in Mexico.

Many immigration experts say a president can steer policy to some extent, but that numerous other factors affect border security – from global migration trends to job prospects in the U.S. to Congress’ willingness to allocate funding for things like border agents and immigration judges. Both sides agree that the asylum system is broken and needs an overhaul.

“Because of existing law, whether [asylum-seekers] make that claim at a legal port of entry or are just caught crossing the Rio Grande illegally, once they do, the border agents are required to begin their processing,” says Gary Schmitt of the American Enterprise Institute by email. “So, while there are various things the president might try and do with executive orders, the biggest thing that needs addressing is only something the Congress can fix.”

Indeed, Mr. Trump and his GOP allies repeatedly urged congressional action during his tenure. And as recently as December 2023, GOP Speaker Johnson called for statutory reforms to be enacted, though he also called on Mr. Biden to use a 1965 provision known as 212(f) that allows the president to restrict or suspend the entry of migrants he deems “detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

While both parties have increasingly sought to accomplish their policy goals through executive action, experts across the spectrum say that only Congress can and should enact more sweeping changes on an issue this complex and important – unless voters want a monarch instead of a president.

The Senate deal, brokered by a Democrat, an independent, and a Republican, would give the president the authority to shut down the border when the daily average of illegal crossings over a seven-day period reaches 4,000. It would require him to do so when that figure reaches 5,000. In the past several months, the U.S. has hit that average all but one week, according to the GOP negotiator, Sen. James Lankford. It also raises the threshold for asylum-seekers and adds penalties for deportees who try to cross again.

Both hard-line Republicans who say the deal would normalize thousands of illegal crossings a day, and progressive Democrats seeking more comprehensive reforms, have taken issue with talk about “shutting down” the border.

“Is there a door that rolls down?” asks New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, saying the lack of specificity suggests the rhetoric is more political than practical.

“It becomes more of a slogan” than actionable policy, says lawyer Muzaffar Chishti, a senior fellow with the Migration Policy Institute. “Let’s say [Mr. Biden] says, ‘I’m going to expel everyone.’ You can’t expel people to Mexico unless Mexico accepts them.”

Indeed, though Speaker Johnson has called for renegotiating Remain in Mexico, Mexico now opposes the policy. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump has urged House Republicans not to compromise on border security – a stance consistent with his record but one that would also likely benefit him politically in this year’s presidential election. Even if the border deal were to somehow pass the Senate, Speaker Johnson has declared it “dead on arrival” in the House.

“Illegal immigration is illegal; it is against the law. Why would you tolerate 5,000 a day before you sought to suddenly enforce the law?” asked Mr. Johnson, a constitutional lawyer, last week. “The goal should be zero, not 5,000 – and all the president’s authority should be utilized at zero.”

Today’s news briefs

• Michigan shooter’s mother guilty: A jury found Jennifer Crumbley guilty of involuntary manslaughter. Her son used a family gun to kill four students at Oxford High School in 2021.

• U.S. secretary of state tours Middle East: Antony Blinken met with Egyptian leaders to secure a cease-fire in the Israel-Hamas war in exchange for the release of hostages.

• Trump immunity claims rejected: The federal appeals court’s decision sets the stage for additional appeals. It is the second time in two months judges have spurned the argument.

• NCAA athletes can unionize: This will allow players to negotiate over salary and working conditions, including practice hours and travel.

US confronts ‘Axis’: Can Iran’s allies be deterred?

Alongside the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, Iran’s allies in the region and U.S. forces have engaged in scores of attacks and retaliations. Both the United States and Iran say they want to avert a wider war, but the intensity of the clashes has increased.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Since the Hamas-Israel war erupted Oct. 7, Iran-backed militias in Iraq and Syria have mounted more than 165 attacks against U.S. military bases in the region. After a cross-border drone strike killed three American soldiers in Jordan last week, the United States vowed to “hold accountable” those responsible.

American warplanes launched 85 strikes Friday against militias allied to Iran, and the U.S. promised more retaliation to come as it targets weapons stockpiles and command-and-control infrastructure of Iran’s self-declared “Axis of Resistance.”

From Lebanon through Syria, and Iraq to Yemen, the Iran-led “Axis” has been active in targeting Israel and its closest ally, the U.S. While the militias’ autonomy provides Iran with a degree of deniability, analysts say the current escalation is dangerously prone to overreach and miscalculation that could lead to a direct U.S.-Iran conflict.

Where is this headed?

For years, the U.S. has “struck [Iran-backed militias’] weapons depots and tried to financially strangle them through sanctions, and yet the groups have kept their capabilities and still operate across the region,” says Renad Mansour at the Chatham House think tank in London.

“What’s becoming clear,” he says, “is the U.S., for all its military and economic might, fundamentally has a predicament: It does not have a sustainable approach for dealing with these groups.”

US confronts ‘Axis’: Can Iran’s allies be deterred?

Since the Hamas-Israel war erupted Oct. 7, Iran-backed militias in Iraq and Syria have mounted more than 165 attacks against U.S. military bases in the region. After a cross-border drone strike killed three American soldiers in Jordan last week, the United States vowed to “hold accountable” those responsible.

American warplanes launched 85 strikes Friday against militias allied to Iran, and the U.S. promised more retaliation to come as it targets weapons depots, rocket stockpiles, and command-and-control infrastructure of Iran’s self-declared “Axis of Resistance.”

From Lebanon through Syria, and Iraq to Yemen, as well as in Gaza, the Iran-led “Axis” has been active in targeting Israel and its closest ally, the U.S. While the militias’ autonomy provides Iran with a degree of deniability, analysts say the current escalation is dangerously prone to overreach and miscalculation that could lead to a direct U.S.-Iran conflict.

American troops number 2,500 in Iraq and 900 in Syria, nominally to prevent a resurgence of the Islamic State (ISIS). But the uptick in militia attacks and the scale of U.S. counterstrikes – which sparked outrage among Iraqi officials – have effectively stalled U.S.-Iraqi talks underway prior to Oct. 7 that were progressing toward a long-term American withdrawal plan.

Who are Iran’s allies in Iraq?

When Islamic State fighters swept from Syria into Iraq and to the gates of Baghdad in June 2014, the U.S.-trained and equipped Iraqi military disintegrated. Yet Iran – which had supported Shiite militias in Iraq for years, as part of an insurgency against American occupation – immediately sent weapons and ammunition to Iraq, and helped marshal and support the newly formed, mostly Shiite Popular Mobilization Forces to fight back.

For years, U.S. airstrikes against ISIS were conducted in parallel with ground forces of the Iran-backed militias and reconstituted Iraqi armed forces. After ISIS was declared defeated in Iraq in late 2017, those Shiite militias – which have at times numbered more than 65 different groups – had sizable political clout and were officially brought under the wing of the Iraqi security forces.

Pro-Iran factions helped violently quell popular street protests that started in 2019, and since October 2023 have operated under the umbrella name of the Islamic Resistance of Iraq, which includes Kata’ib Hezbollah – one group long at the forefront of attacks on U.S. bases.

How much control does Iran have over its “Axis”?

“This is a set of armed groups that are closely aligned to Iran, and at times will take orders from Iran – but at other times will diverge; they do have some autonomy,” says Renad Mansour, head of the Iraq Initiative at the Chatham House think tank in London. “The word ‘proxy’ here is difficult, because it implies just working entirely on behalf of someone else. These groups have their own interests.”

Both Tehran and Washington have signaled repeatedly that they do not want a wider war that would put the two archfoes into direct conflict. Immediately after the three Americans were killed in Jordan, for example, Kata’ib Hezbollah claimed responsibility.

But then after direct intervention by Brig. Gen. Esmail Qaani, commander of Iran’s Qods Force, which handles the “Axis” across the region, and Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, the militia issued a statement saying it would cease all attacks on Americans – and even indicated that it had been unhappily pressured by Iran.

“The logic of violence that Iran wants is to show force, but not to risk any escalation,” says Dr. Mansour.

Can the U.S. degrade the “Axis” from the air?

The record of achieving lasting militia degradation through airstrikes alone is not very promising, if the U.S. military experience in Afghanistan and Iraq is any measure.

U.S. Central Command says it struck seven different targets in Iraq and Syria. With the help of Britain and other regional partners, it has also been launching almost daily strikes against another Iran-backed group, the Houthis in Yemen, who have not been deterred from targeting Red Sea shipping.

One month ago, a U.S. drone strike in Baghdad killed a leader of the Harakat al-Nujaba militia, accused of planning attacks against American service members. Back in 2020, also in Baghdad, the U.S. assassinated Iran’s Maj. Gen. Qassim Soleimani, the Qods Force commander and architect of the “Axis of Resistance,” along with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, founder of Kata’ib Hezbollah and deputy leader of the Iraqi Shiite militia forces.

In addition to such targeted killings, for years, the U.S. has “struck [Iran-backed militias’] weapons depots and tried to financially strangle them through sanctions, and yet the groups have kept their capabilities and still operate across the region,” says Dr. Mansour.

“There can be intense military bombardment to go after adversaries, but that does not make a coherent strategy,” he says. “What’s becoming clear is the U.S., for all its military and economic might, fundamentally has a predicament: It does not have a sustainable approach for dealing with these groups.”

How are the U.S. strikes impacting Iraq?

While Washington aims to deter further attacks on U.S. forces, the stepped-up militia action linked to the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza and the new level of kinetic American response touch a raw nerve in Iraq.

“We already know the damage that the Americans can do – that’s the whole political sensitivity of this issue,” says Hamzeh Hadad, an Iraq expert and visiting fellow with the European Council on Foreign Relations. “So the Iraqis don’t need a reminder of what the Americans are capable of, which is why we always had that fear of, ‘Will this extend to that level?’”

And there is another practical concern, he says, about the continuing threat from the Islamic State. In Syria and Iraq, for example, the U.S. Department of Defense estimates that 1,000 dispersed ISIS fighters remain, and camps in Syria still hold tens of thousands of people linked to the original ISIS “caliphate.” Likewise, nearly 100 people were killed in Iran a month ago, in a double explosion claimed by the ISIS Khorasan branch.

“When this Iraqi militia decided to attack this American base bordering Iraq, Syria, and Jordan, you are arguably attacking a side that is keeping ISIS in check there,” says Mr. Hadad. “And the same can be said for the Americans: When they attack the bases on the border of Iraq and Syria, they are also attacking [militias] that are basically stationed on the border to take care of ISIS.”

The confidence crisis facing Boeing and Cruise

Citizens depend on businesses to be truthful, especially around safety. When trust erodes, companies must act quickly or lose customers. That’s the situation U.S. firms Boeing and Cruise face now.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

When companies make an honest mistake, customers are usually willing to forgive. When they make a series of errors or are found to be lying about a practice or a mistake, it’s harder to rebuild trust.

That’s the dynamic now playing out at two U.S. companies – old-guard Boeing charged with skirting safety rules with its 737 Max jets, and upstart Cruise, a driverless car company now under investigation over its handling of a robotaxi collision. The failures highlight ethical concerns at a time when public confidence in institutions generally – and in large tech companies specifically – has deteriorated.

This deterioration may complicate the prospect of corporate redemption for both Boeing and Cruise. “The FAA will consider the full extent of its enforcement authority to ensure the company [Boeing] is held accountable for any non-compliance,” Michael Whitaker, administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration, told a House committee Tuesday. It may also make it harder for other tech companies to push innovations – from artificial intelligence to gene therapies to robots – on a doubting public.

Yet public confidence remains as important to business as to society.

“Trust is kind of like the grease of a productive and positive relationship,” says Jonathan Bundy, a professor at Arizona State University.

The confidence crisis facing Boeing and Cruise

When companies make an honest mistake, customers are usually willing to forgive. When they make a series of errors or are found to be lying about a practice or a mistake, it’s harder to rebuild trust.

That’s the dynamic now playing out at two U.S. companies – old-guard Boeing charged with skirting safety rules with its 737 Max jets, and upstart Cruise, a driverless car company now under investigation over its handling of a robotaxi collision. The failures highlight ethical concerns at a time when public confidence in institutions generally – and in large tech companies specifically – has deteriorated.

This deterioration may complicate the prospect of corporate redemption for both Boeing and Cruise. “The FAA will consider the full extent of its enforcement authority to ensure the company [Boeing] is held accountable for any non-compliance,” Michael Whitaker, administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration, told a House of Representatives committee Tuesday in prepared remarks. It may also make it harder for other tech companies to push innovations – from artificial intelligence to gene therapies to robots – on a doubting public.

Yet public confidence remains as important to business as it is to society.

“Trust is kind of like the grease of a productive and positive relationship and a positive reputation,” says Jonathan Bundy, a management professor at Arizona State University. “Once that trust starts going away, it becomes much more difficult to just say you’re sorry.”

Boeing’s most recent problems began on Jan. 5, when shortly after takeoff from Portland, Oregon, a panel of one of its 737 Max 9s blew out. Despite loss of pressurization, passengers suffered only minor injuries, and the Alaska Airlines crew was able to return to Portland. The FAA grounded all the Max 9 planes with the special panel – actually a “plug door” used to seal off unused emergency exits – after loose bolts were found on other Max 9 plug doors.

On Tuesday, federal investigators, in a preliminary report, said there was evidence that four bolts designed to hold the plug door in place on the Boeing 737 Max 9 were missing when it blew out.

A day earlier, The Boeing Co. said it needs to address a new problem with fuselages on some unfinished 737 jets. Two holes on each plane not drilled to required specifications will force the company to rework about 50 planes, raising further concerns about quality at the manufacturer and its suppliers.

The grounding was similar to an earlier Boeing debacle, when the FAA forced the company to ground its 737 Max planes after two crashes in 2018 and 2019, resulting in 346 fatalities. In those crashes, Boeing initially blamed pilot error. But investigators pinned the cause on software changes that took control of the planes away from pilots without their knowledge – a problem Boeing knew about a year before the first crash but did not tell airlines, pilots, or regulators. Boeing lost billions in sales to rival Airbus.

Eventually, the company apologized, instituted new safety procedures, and brought on a new CEO to clean up the mess. It is that CEO, David Calhoun, who faces the task of rebuilding trust once again.

Some travelers have avoided booking on Boeing’s 737 Max planes, even if that means paying extra for a different flight. Public forgiveness will depend, at least in part, on whether people believe the latest problems represent unrelated mistakes or reflect a pattern in which the company consistently puts profits ahead of safety.

“There’s lots of research that says that a breach of trust based on competence is something that is easier to recover ... from,” says Sandra Sucher, a professor at Harvard Business School and co-author of a 2021 book “The Power of Trust: How Companies Build It, Lose It, Regain It.” But “persistent breaches of competence begin to look almost like a breach of integrity.”

And moral failure is much harder for a corporation to recover from.

“Even if they address this one specific issue with the doors, if the broader culture is not changed to address the safety issue, then why would we place faith in the organization?” asks Peter Kim, a professor of management and organization at the University of Southern California’s business school and author of the 2023 book “How Trust Works: The Science of How Relationships Are Built, Broken and Repaired.”

High-tech products are complex, involving so many parts and procedures that it’s not fair to jump to conclusions before all the facts are in, Dr. Kim adds.

“A flawed corporate culture”

Sometimes, it’s a fine line between mishap and a flaw in corporate culture.

On Oct. 2, 2023, a driverless taxi owned by Cruise was moving through an intersection in San Francisco when another driver hit a pedestrian, propelling her into the path of the robotaxi, which ran over her. The initial collision was clearly the fault of the human driver, who fled the scene. Anxious to prove it wasn’t at fault, Cruise quickly provided the press the portion of the video that it could download remotely from the robotaxi, which showed only what happened up until the Cruise taxi hit her.

Hours later, when Cruise employees could download the full video from the car, they found something more chilling. After running over the pedestrian, the car stopped, and then immediately started up again to pull over to the side of the street, dragging the woman some 20 feet, even though she was visible to one of the car’s left-side cameras.

While even an attentive human driver might have accidentally hit the woman in the first place, they certainly would have investigated the situation before starting up again, a third-party technical analysis later determined.

Cruise made no effort to alert the media to the dragging incident. The following day, when it showed the full 45-second video to regulators, employees let the video speak for itself, according to a third-party investigation of the incident paid for by Cruise and released late last month. That decision not to speak up about the incident proved the company’s undoing.

In three initial meetings with government officials, internet connectivity issues probably made it difficult – or impossible – to see the dragging incident, the report concluded. The California Department of Motor Vehicles, claiming it was not shown the full video, suspended Cruise’s permit to operate driverless cars. The company may not have intended to deceive regulators, the report says, but neither did it tell the whole truth.

Reluctance to admit mistakes is not unusual among corporations. “Top executives at the firm, directors, the one thing in their mind, I suppose, when they wake up and when they go to bed is litigation risk,” says Sandra Vera-Muñoz, professor of accountancy and a fellow at the Notre Dame Deloitte Center for Ethical Leadership at the University of Notre Dame. “So of course they’re going to try to find ways of denying responsibility.”

But Cruise’s actions were also the result of a flawed corporate culture, the report concluded, including “poor leadership, ... an ‘us versus them’ mentality with regulators, and a fundamental misapprehension of Cruise’s obligations of accountability and transparency to the government and the public.”

Restoring confidence

General Motors Co., which owns Cruise, has taken the first steps to rebuild confidence, trust researchers say. It paused all autonomous vehicle operations. It has apologized: “We are profoundly remorseful both for the injuries to the pedestrian, as well as for breaching the trust of our regulators, the media, and the public,” it said in a Jan. 25 blog post. It has made efforts at transparency by releasing the report and a redacted version of the third-party technical analysis. A dozen key Cruise executives, including co-founders Kyle Vogt and Daniel Kan, are gone. GM has named a chief safety officer to the operation.

Boeing, grappling with its more recent plug door incident, is following a similar path. On an earnings call on Jan. 31, the company’s CEO, Mr. Calhoun, owned that Boeing was responsible for the equipment failure. “An event like this must simply not happen on an airplane that leaves one of our factories.”

The company has put in place more quality controls and inspections, appointed an adviser to independently review its quality control, and allowed client airlines access to its factories in a bid to increase transparency as it awaits a federal investigation’s findings.

“It’s saying the right things, but I think it’s too early to tell how much better their inspections are,” says Bill Benoit, author of “Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies: Image Repair Theory Extended.”

If customers conclude that the problem lies in the corporation’s character, the repair process could take years, trust researchers say.

The flip side is that companies that do the hard work of real reform can become stronger as a result. For example, in the 1990s, accused of working with Asian contractors using child labor in sweatshop conditions, Nike initially denied the reports. Eventually, it owned up to its mistakes and instituted quality controls to ensure Nike’s contractors and subcontractors treated workers fairly.

“They internalized the mistake to say ... ‘We’re going to change the culture of the organization to ensure that something like that never happens again,’” says Professor Bundy. “Now, they’re generally celebrated as a bit of a champion on this issue.”

Such trust is sorely needed at a time when confidence in big business and large tech firms is at record lows, according to Gallup. Trust in tech firms is key because the public is looking to these companies to manage technology, according to the 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer, released last month. But the international survey found that most respondents felt innovation is poorly managed, which will require companies to address public concerns.

“Innovation is accelerating and should be a growth enabler,” Richard Edelman, CEO of Edelman, said in a press release. “But it will be stymied if business doesn’t pay as much attention to [public] acceptance as it does research and development.’’

A little schoolhouse fights to keep Mohawk language alive

Preserving a treasured language can help sustain a way of life. One school has made that its mission.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

Riley Robinson Staff photographer

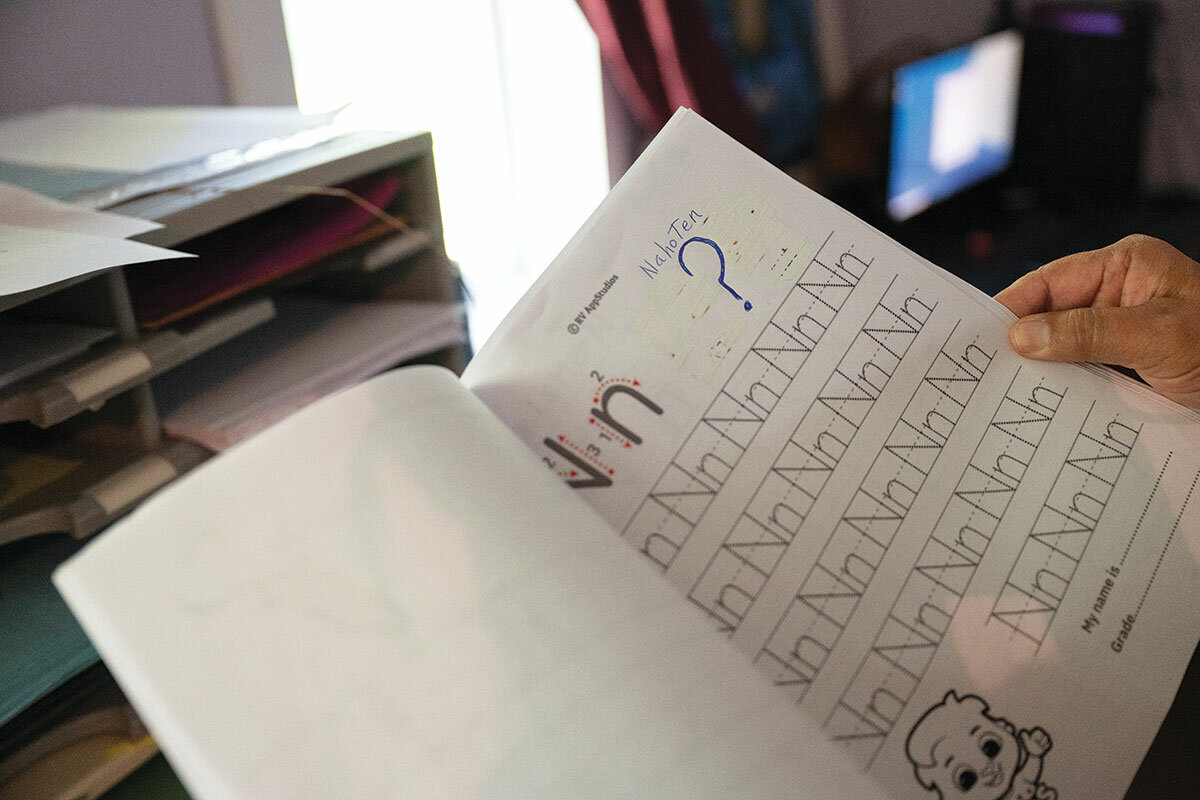

For decades, a little schoolhouse at the United States-Canada border has been fighting to preserve Mohawk language and culture.

“This makes us who we are,” says Kawehnokwiiosthe, a teacher at the Akwesasne Freedom School.

She turns to her young pupils, who introduce themselves by their clans – Wolf, Bear, and Eel – and state that they are wisk, or age 5. Every class in K-8 that students take is full language immersion.

Most parents pay tuition with a quilt sold at an annual auction in August. Parents do the cleaning (along with the students) and the maintenance work. Students come from the American and Canadian sides of the border, but the school has never accepted funds from either government, says Alvera Sargent, who heads the nonprofit Friends of the Akwesasne Freedom School.

Waylon Cook, project manager of the school’s nonprofit arm, says first-language Mohawk speakers are treasured here. “If you lose [the language], you can’t go to France like you could to learn French,” he says. “There is nowhere else to do it but here.”

A little schoolhouse fights to keep Mohawk language alive

Students and teachers, as well as some parents, sit on two wooden benches running the length of the hallway of their school, organized not by age or grade but by their clans.

They take turns reading from the Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen, which translates from the Mohawk language to “Words before all else.” These words, which recognize all life forces in creation, mark the day’s start at the Akwesasne Freedom School.

But the 60-odd students here wouldn’t understand these lessons if it weren’t for this little schoolhouse at the United States-Canada border that for decades has been fighting to preserve Mohawk language and culture. “This makes us who we are, and if we don’t have this, who are we going to be?” asks teacher Kawehnokwiiosthe, whose name in English means “She makes the island beautiful.”

“This is more than just language; it teaches us how to live,” she says.

Kawehnokwiiosthe turns to her young pupils, who introduce themselves by their clans – Wolf, Bear, and Eel – and state that they are wisk, or age 5. Every class in K-8 that students take is full language immersion. When a child asks a question in English, Kawehnokwiiosthe responds in Mohawk.

Most parents pay tuition with a quilt sold at an annual auction in August. The school is run as a co-op, where parents do the cleaning (along with the students) and the maintenance work. Students come from American and Canadian sides of the border, but the school has never accepted funds from either government, says Alvera Sargent, who heads the nonprofit Friends of the Akwesasne Freedom School and is one of the last first-language speakers of Mohawk.

That makes her precious, says Waylon Cook, former teacher and now project manager of the school’s nonprofit arm. “We treasure our first-language speakers,” he says. “We treasure them because they are so important for us to continue on our language,” he says. “If you lose it, you can’t go to France like you could to learn French. There is nowhere else to do it but here.”

In 2021, Indigenous leaders in Kamloops, British Columbia, announced that they believed they found the remains of over 200 children on the site of the former residential school there. It shocked Canada, and spurred the search for hundreds more unmarked graves.

For Mr. Cook, the Akwesasne Freedom School has always been the path to justice for Indigenous children abused at residential schools – by being cut off from their language, spirituality, and way of life. The Akwesasne Freedom School offers the opposite of what residential schools did. “This is our own solution,” says Mr. Cook. “They’ve made it so hard to be who we are. And we won’t give up the fight to maintain our language and culture.”

On Film

‘Perfect Days’ asks what constitutes a happy life

What does it mean to live a life of meaning? “Perfect Days,” directed by Wim Wenders, offers proof that the rhythms of everyday life can resonate when beheld by an artist’s eye, writes the Monitor’s film critic, Peter Rainer.

‘Perfect Days’ asks what constitutes a happy life

“Perfect Days” is about a man who cleans public toilets in Tokyo for a living. For the first half hour or so, we follow him as he wakes up at dawn in his small, spartan apartment. He suits up, mists his plants, trims his mustache, sips coffee, and drives his equipment truck into the city. There, with uncomplaining efficiency, he wordlessly goes about his business.

Don’t let this description put you off. It’s a wonderful movie, and an Oscar nominee for best international feature. It is also proof, if any were needed, that the rhythms of everyday life, no matter how seemingly mundane, can resonate when beheld by an artist’s eye.

The artist here is the German-born Wim Wenders, who also co-wrote the script with Takuma Takasaki. It’s Wenders’ first dramatic feature in Japanese after making several documentaries in Japan, including a terrific one on the great director Yasujirō Ozu. At its best, “Perfect Days” shares the same haunting sense of stillness that characterized Wenders’ best work in films such as “The American Friend” and “Wings of Desire.”

Hirayama the cleaner (Kôji Yakusho, the marvelous actor best known for “Shall We Dance?”) leads a methodical, almost ritualistic existence. That morning routine of his is always the same. His drive into the city is always accompanied by cassette tapes of Patti Smith, Lou Reed, Nina Simone, and The Animals. (That group’s “House of the Rising Sun” is a particular favorite.) He listens contentedly but doesn’t sing along.

During lunch breaks, he sits in a local park and takes photos of the trees and the blue sky. After work, he visits a local sauna and then usually stops at a favorite diner. Occasionally he checks out a bookstore, where he buys novels by William Faulkner and Patricia Highsmith for a dollar. He reads them at night, lying down, by lamplight.

What has led Hirayama, a man of obvious culture and smarts, to such a spare life? Wenders doesn’t attempt to fill in the blanks for us. Hirayama is not presented as a clinical case or a puzzle to be solved. If we were expecting a startling revelation about some great hurt in his past, it never comes. Still, there are hints. His playful teenage niece, Niko, (Arisa Nakano), whom he has not seen for some time, unexpectedly comes to stay with him after a spat with her mother, Keiko, (Yumi Asô), Hirayama’s estranged sister.

Niko, who accompanies her uncle on his rounds, wants to know why he and her mother don’t get along. His only answer is that they live in different worlds. When Keiko shows up to retrieve her daughter, there is no rancor. We see her sadness at her brother’s life, but also the love they still furtively bear for each other.

Should she be sad for him? She does not see Hirayama as we do. He is living a life that offers up its small serenities. He takes great pleasure in photographing the beauty of the trees and the sky. People are drawn to him – Niko, a lost child in the park, the bookseller, a transient homeless man. Hirayama’s jabbery young cleaning assistant, Takashi (Tokio Emoto), asks him how he can be so devoted to such a job. Takashi is flabbergasted, and somewhat awed, by Hirayama’s equipoise.

As portrayed with unstinting dignity by Yakusho, Hirayama defies our easy assumptions about what constitutes a happy life. When he and Niko are out riding bicycles, his unruffled repose inspires her. He wants her to live in the moment. “Next time is next time. Now is now,” he says to her, and she turns his words into a jingle that they both joyfully join in on.

There is no catharsis to this story, no dramatic denouement. Hirayama’s unknowability represents the mystery of what people truly carry inside themselves. If he remains an enigma, he is an enigma touched by grace.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Perfect Days” is rated PG for some language, partial nudity, and smoking.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Ceaseless forgiving in Spain

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Any democracy fragmenting over political differences might take a lesson from Spain in recent days on how to build unity. Last week, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez sustained a political loss when a bill offering amnesty to separatists from the province of Catalonia was voted down in parliament. The blame for the loss went to one of the secessionist parties. Some in Spain called for reprisals. But the government has responded instead with compassion.

Spain is experiencing its worst drought in 1,200 years. The effects are direst in Catalonia, which hasn’t seen rain in more than a thousand days. Madrid yesterday announced a plan to invest $502 million in new desalination plants in Catalonia and will soon start shipping in water.

The amnesty bill, which has now gone back to committee for further debate, and the drought measures reflect an effort by the prime minister to heal divisions through “dialogue, generosity and forgiveness,” as he said last November.

Unlike attempts at reconciliation in other countries with high conflict, his approach has not made forgiveness conditional on terms such as remorse or disclosure.

Ceaseless forgiving in Spain

Any democracy fragmenting over political differences might take a lesson from Spain in recent days on how to build unity.

Last week, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez sustained a political loss when a bill offering amnesty to separatists from the province of Catalonia was voted down in parliament. The blame for the loss went to one of the secessionist parties, Together for Catalonia, or Junts. Some in Spain called for reprisals. But the government has responded instead with compassion.

Spain is experiencing its worst drought in 1,200 years. The effects are direst in Catalonia, which hasn’t seen rain in more than a thousand days and last week declared a state of emergency. Madrid yesterday announced a plan to invest $502 million in new desalination plants in Catalonia and will soon start shipping in water. That follows an earlier decision to forgive $17.5 billion owed by the province to the national government in debt and interest.

The amnesty bill, which has now gone back to committee for further debate, and the drought and debt measures reflect a patient, ongoing effort by the prime minister to heal divisions through “dialogue, generosity and forgiveness,” as he said last November. Mr. Sánchez took office in 2018, just eight months after the Junts held a referendum on Catalonia independence despite a Supreme Court ruling declaring the ballot unconstitutional.

Unlike attempts at reconciliation in other countries with high conflict, his approach has not made forgiveness conditional on terms such as remorse or disclosure. He sees reconciliation as a shared and negotiated outcome between two sides of a dispute. Forgiveness, as many theologians note, is an individual act – “a private and ongoing discipline of mind, heart, and soul,” wrote Loyola Press author Vinita Hampton Wright.

It can also require grace from one side. Forgiveness “can be done not by the one who is more at fault, but by the one who has more mental and spiritual strength,” wrote Stanisław Glaz, a professor at Jesuit University Ignatianum in Kraków, Poland.

The amnesty bill triggered street protests from hundreds of thousands of Spaniards. Carles Puigdemont, the Catalan leader who fled into exile in Belgium following the referendum to avoid arrest, has said Catalonians need not ask for forgiveness because they have done nothing that needs to be forgiven. That has not dissuaded Mr. Sánchez. In 2021, he pardoned nine secessionist leaders jailed for their roles in the separatist bid.

“Almost always to reach an agreement,” he said then, “someone has to take the first step. We are going to rebuild social harmony from respect and regard. We cannot start from scratch, but we can start again. We love you Catalonia.”

Will that soft approach be just the right solvent? As Omar Encarnación, a chaired professor of politics at Bard College in New York, noted recently, support for secession has dropped sharply in Catalonia since 2017 – below 40% in one recent poll.

It “remains unclear that Sánchez can sell amnesty to a very skeptical Spanish public,” Professor Encarnación wrote in Foreign Affairs. But “restoring peace to Catalonia is a step in the right direction.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Holy joy

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Deb Hensley

Singing the song of divine Soul’s goodness brings comfort and healing.

Holy joy

“Joy is a protest.” I wrote those words on a sticky note a while ago and posted it in the center of my bathroom mirror. I put it there to remind me that even when things look bleak, spiritual joy is an active, unstoppable healing power.

Then some tragic things happened: a mass shooting in my state and more reports of inhumane deprivation in war zones. Who can be cheerful in the midst of human suffering? I wanted to rip the note off the mirror and stuff it in the trash.

But after a while, I realized that this was the exact right time for staying the course and practicing true, holy joy – joy derived from Soul, God.

Infinitely tender, this joy is so much more than a humanly generated state of personal cheer. Soul-joy involves the deep conviction that good is supreme and at hand. This kind of God-sourced conviction is rooted in the understanding that man is divinely created, entirely spiritual, innocent, unharmed, complete, and safe.

Soul-joy, then, is wholly able to affirm this radical spiritual fact proclaimed in the Christian Science textbook: “Evil is not supreme; good is not helpless; nor are the so-called laws of matter primary, and the law of Spirit secondary” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 207).

God-sourced joy is constant. It reflects the pure light of Truth. And it’s often accompanied by angel messages from God that soundlessly and compassionately go about repairing broken hearts and healing minds and bodies. There’s not one news report that can get under its skin, not one anxious thought, threatening storm, or terror that can shake it. Soul, being infinitely intelligent and all-knowing, lifts each call for help far above human strife into “the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding” (Philippians 4:7, New King James Version).

As a spiritual quality, joy is indispensable in protesting what Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, called “the ghastly farce of material existence” (Science and Health, p. 272) and affirming what Christ Jesus taught – the spiritual Truth that makes us free. This changes our standpoint and thus our perceptions.

One day some years ago, I wasn’t feeling very joyful. It was a bleak winter day, and someone dear to me was in trouble. I couldn’t focus on anything else. Fear was like a ferocious tiger camped in my living room. Everything seemed overwhelming, sad, and desperate.

Then I found myself starting to quietly sing. It was a soft, unbidden melody, and I didn’t recognize it at first. But a little later I remembered a verse to the hymn:

The light of Truth to us display,

That we may know and choose Thy way;

Plant holy joy in every heart,

That we from Thee may ne’er depart.

(Simon Browne, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 39, © CSBD)

It was exactly the message I needed: holy joy.

As I prayed with that hymn, I felt the power of holy joy taking root in my heart and mind. I called it my holy joy tree. For weeks afterward, every time the fear came up, I faced it down with the power of that unshakable holy joy. Over the next few weeks, this work yielded the fruits of spiritual sense – the opposite of material belief – confidence, comfort, and light. The debilitating fear gave way to peace. As Soul-joy prevailed, the desperation dissipated. And my dear one was safe.

Joy is not for the faint of heart. In fact, practicing holy joy is one of the strongest things we can do. Joy is a powerful, ongoing affirmation of good that is especially needed when things get rugged. Claiming it more recently, I felt a significant shift toward the healing of a protracted health problem that I eventually experienced.

I love thinking of joy as what it really is: our built-in resilience. Soul-joy heals our grief. It lifts desperation off our concept of ourselves and others, resists polarization, and unifies. It banishes heaviness and melts the mist of mental fog and illness. It is an active agent in healing limited, material beliefs, including sickness and sin. Moreover, Soul-joy is a tireless Truth-witness.

And here’s another thing I’m learning: Joy and gratitude are best friends. They walk in total safety together through dark places of fear. I’ve even heard them laughing at storms, confidently riding the fiercest winds with their other trusty companion – courage.

I think I’m going to need a lot more sticky notes.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Jan. 18, 2024.

Viewfinder

Marking milestones

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, staff writer Jackie Valley will shed light on a first-of-its-kind guilty verdict of involuntary manslaughter. The jury found Jennifer Crumbley criminally responsible for a mass shooting by her son, who used a gun his parents bought him.