Maine’s open door for refugees meets a housing shortage

Loading...

| Portland, Maine

Linode Lafleur left Haiti after the United Nations agency she worked for closed, and gangs in Haiti threatened her family. Her journey to America took her from Haiti to Chile to Bolivia to Peru to Ecuador to Colombia. Through the jungle into Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico. Much of it on foot.

At last, she found hope in Portland, Maine. “I love it here. I will never leave,” she says.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA city in Maine known for embracing immigrants is straining to handle the most recent surge. It is trying to balance two competing interests: compassion and limited resources.

Migrants from Africa and the Caribbean especially have come to Portland because they heard it had received fellow travelers humanely. But a recent influx of asylum-seekers is testing the city’s capacity.

When shelters filled, the city put people up in motels, amid COVID-19- and winter-created vacancies. But now the innkeepers want their rooms back for tourists. An affordable housing shortage led Portland’s city health director to tell agencies working on the southern border that immigrants “are no longer guaranteed shelter upon their arrival.” Amid a collision between the community’s sense of hospitality and its limited resources, Portland has stopped its housing assistance beyond giving out legally required vouchers, though churches and nonprofits continue to step in.

Still, the state wants new arrivals, says Greg Payne, senior housing adviser to the governor. So the question looms, “How do we moderate the pace of arrivals in a way that prevents it from becoming a humanitarian crisis when they arrive?” he says.

Even now, alive and safe, Linode Lafleur cries at memories of the jungle. The Haitian woman and her family were lost for days struggling to get to the United States.

No food, no rest. Fording chest-high rivers that swept many others away. Bodies by the path. Treacherous cliffs, so steep, so hard. Only the pleas of her 4-year-old son kept her going. “I wanted to throw myself off the cliffs. I wanted to die,” she says.

Haiti to Chile to Bolivia to Peru to Ecuador to Colombia. Through the jungle into Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico. Much of it on foot.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA city in Maine known for embracing immigrants is straining to handle the most recent surge. It is trying to balance two competing interests: compassion and limited resources.

All to suffer again, this time from men instead of chasms. Tricked, kidnapped, robbed at gunpoint in Mexico. Stripped of what little they had. Their son held up by his legs as thieves stole his clothing. Ms. Lafleur’s husband, gun to his ear, desperately crying, “Why are you doing this? We are just looking for a life!”

All to get to a new land. All to find shelter and safety in a small town in a northern corner of America, a town that has opened its doors, welcomed the strangers, but is struggling under the burden. A town that says it cannot take any more.

Portland, Maine, population 68,000, is 84% white and tucked snugly away from any border problems – the Canadian border five hours away catches the occasional migrant walking north into Canada.

Yet the city that has been one of the most benevolent in America toward outsiders now finds itself with 1,200 newcomers, most from Africa and the Caribbean. They have come to Portland because they heard it had received fellow travelers humanely. Most speak no English; they have no money, no relatives or friends to house them; and they are not allowed to work for a living as their appeals for asylum slowly crawl through the system.

Its shelter filled, the city has put them up in motels while COVID-19 and winter created vacancies. But now the innkeepers want their rooms back for tourists, and Portland has no place to put them.

And still they keep coming.

Portland’s city health director took the extraordinary step in May of emailing agencies working on the southern U.S. border, telling them that immigrants “are no longer guaranteed shelter upon their arrival” in the city. The adjoining municipality of South Portland sent a similar message, and 79 local aid organizations followed with letters to the state of Maine and the federal government saying they were stretched too thin.

“We are at capacity, just unable to manage anymore,” says Danielle West, the interim city manager of Portland.

The announcements have brought cries that an urban area known for its welcoming culture now wants to shut its doors.

What does a city do when its ethos of compassion collides with the reality of no vacancy? How many refugees are too many?

Many places harbor a sense of benevolence toward outsiders. In remote parts of Alaska, people leave their cabin doors unlocked to offer safety to desperate travelers. Middle Easterners still observe the obligation of hospitality to strangers.

Sometimes the welcome comes on a grand scale: More than half of Jordanians are Palestinians. Poland has accepted 3 million refugees from Ukraine.

Sometimes the generosity is quietly personal: Hundreds of Berliners have opened their homes to Syrians fleeing a brutal civil war. They call it Willkommenskultur – welcome culture.

But does the calculation change when newcomers crowd the house? The question is growing in urgency: The United Nations estimates the number of people who have been forced from their homes by wars, violence, hunger, and climate change has now reached 100 million – the highest on record.

Like many places in this country, Portland was forged by immigrants. The first here were native Algonquian-speaking people from Asia who moved in as the glaciers melted 14,000 years ago. Much later came European explorers; French trappers from Canada; settlers from England, Ireland, and France; and some enslaved people brought from Africa. Textile mills and fishing brought Italians, and granite quarries brought Finns.

“Immigration into Maine has been the lifeblood of our state,” says Ethan Strimling, a former mayor of Portland. “Every generation that has built our city has been an immigrant generation. And if we didn’t have the immigration into the state, our population will just be declining dramatically.”

For years, newcomers here made it on their own. Reza Jalali landed in Portland 37 years ago when what he calls his “bad poetry” angered the government of his native Iran. The U.S. offered him refuge. The State Department gave him a book of black-and-white photos to pick a new home.

“The pictures from Maine looked fantastic,” Mr. Jalali recalls. “Except they were all taken in the summer. There should have been a disclosure that said, ‘Please don’t expect this for 11 months of the year,’” he adds, laughing.

But he has stayed, raised a family, earned advanced degrees, taught college, and written books. He is now head of the Greater Portland Immigrant Welcome Center.

Recent arrivals to Maine have made headlines before. Somalis surged to the sagging industrial town of Lewiston in the early 2000s. Their presence brought controversy and pushback – the mayor publicly told others not to come. But the immigrants restored vacant houses, started businesses, and filled the schools with new voices.

In Portland, three years ago, a sudden influx of 450 Africans arrived when Mr. Strimling was mayor. The city scrambled to put cots in the city’s sports arena for two months, private citizens donated nearly $1 million to help, and people opened up spare rooms to house the strangers.

That success, with some irony, helped bring the current wave from Africa. In the cellphone age, immigrants and refugees plumb the internet and contact earlier migrants through WhatsApp. If they make it across the U.S. border, many ask to go to Portland because they’ve heard other Africans are there. It is natural: Travelers “will take the safety of an established community,” says Mr. Jalali. Border agents and aid groups comply. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan sent 100 more refugees to Maine.

Portland helped migrants in ways many other jurisdictions did not. It placed new arrivals in the city’s family shelter until that was filled, and then in motels. The city now has 1,200 immigrants housed in 12 motels across seven jurisdictions, according to local officials.

Other cities and towns often give immigrants vouchers for housing, but require the new arrivals to find dwellings on their own – a daunting task without the language skills, ability to get around, or basic knowledge of a community. Portland also offers vouchers for food – and aid organizations also cook communal African meals. Most of the 350 families who arrived recently have young children; the schools are a chorus of languages. A legion of nonprofit organizations has taken root in Portland that provides legal, transportation, and other assistance to the newcomers.

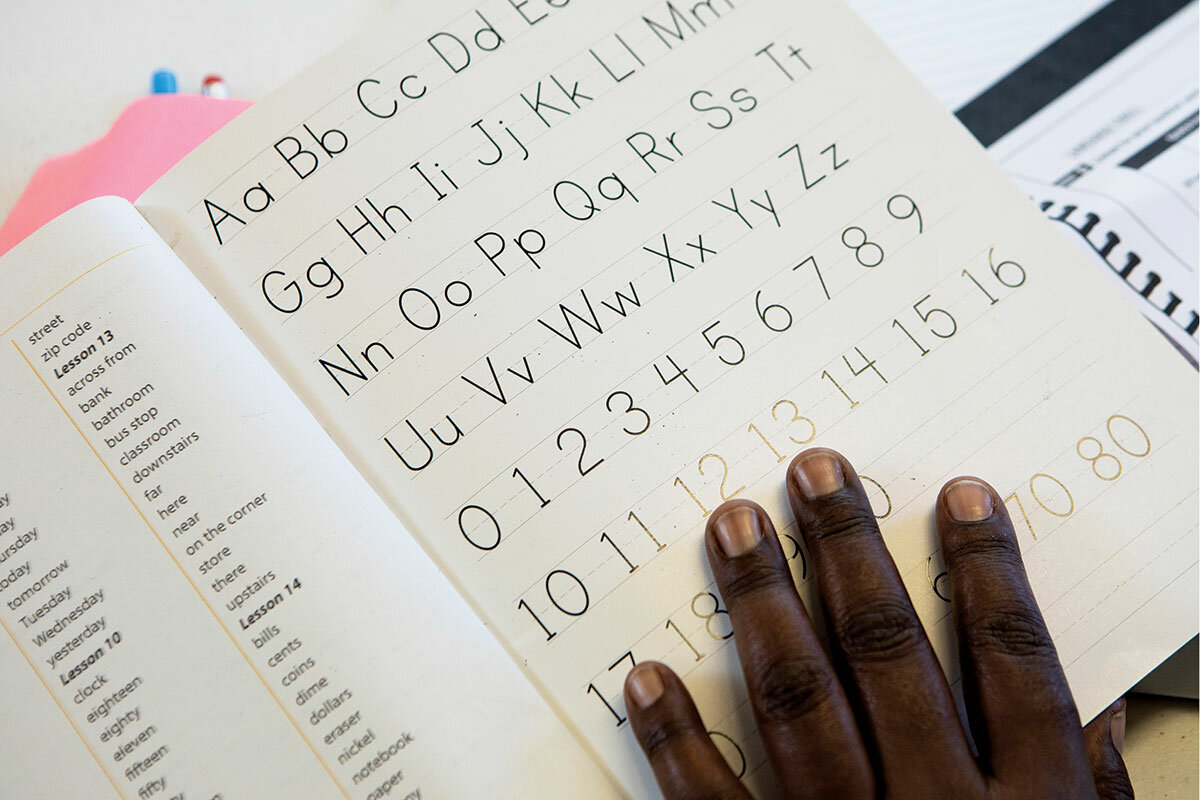

On the ground floor of a Jewish synagogue in South Portland, teachers Dorothy Barker and Joyce Walworth coax seven mothers from Haiti, Angola, and Congo – all of whom undertook unimaginable risks to get here with their families – to brave a new challenge: English.

Today’s lesson is prepositions. Ms. Barker, a community college teacher, is in the classroom sponsored by the nonprofit Immigrant Welcome Center, and she is working hard. She stands on a chair. “Dora is on the chair,” she leads the class. She flops to the floor. “Dora is under the desk,” she chants. She puts a book in a box and calls on Estrella Garcia, from Angola, to make a sentence with in. The woman haltingly succeeds, with some coaching from her classmates, and dissolves into delighted giggles.

“We use singing and dancing and games and a lot of laughing, a lot of me running around with big articulations, and a lot of encouragement,” Ms. Barker says. “They joke, they laugh, they tease each other. And they became friends, I hope.”

“The asylum-seekers have already been through more than I can imagine,” she adds. “Language is the first step to building confidence and ability to access resources.”

Leonora Nganga is in the class after literally jumping out a window to flee Angola. She learned that a man she was living with was violent, she says through a Portuguese interpreter, and fled when he attacked her. She escaped to the capital, Luanda, then to South Africa and later to Mozambique. At each stop, she was pursued by people linked to her former companion, she says. Finally she bought a plane ticket to Panama and started walking north, with her 6-year-old son, Juliano.

It took them eight months to get to the U.S.-Mexico border. A companion on the trip heard about Portland, and when they finally crossed into the U.S., Ms. Nganga asked to go there. Her trip mate journeyed on to Canada.

“Here in Portland I am getting help,” she says, as Juliano squirms beside her. “I can feel good. I can feel safe.”

But this spring, the return of a post-pandemic tourist season brought a crunch in motel rooms, and the continued flow of asylum-seekers overwhelmed Portland’s efforts.

“The number of people that we’re seeing arriving is not something anybody had anticipated,” says Ms. West, the interim city manager. “They just keep coming, coming to Portland.”

In the letter it sent out, the city contacted about 30 aid groups and government agencies working on the U.S. border, urging them to direct asylum-seekers elsewhere. Portland would continue to issue legally required vouchers, but newcomers would have to find housing on their own. The letters brought headlines: Portland says “No vacancy” for asylum-seekers.

The move has not stanched the flow. In her office above a car-rental lot, Mufalo Chitam juggles her phone with a sigh, as she tries to find shelter for the latest unannounced arrivals. She is head of the Maine Immigrants’ Rights Coalition, a nonprofit suddenly thrust into the job of arranging housing when the city stopped doing it May 5.

“That was Motel 6, with four rooms. Two rooms here, five rooms there. My phone is ringing night and day,” she says wearily. “That’s what keeps me busy.”

The other night, she says, a person at the city shelter told her the facility was filled and there were still 28 people outside. “So unless you know somewhere, they’re going to sleep outside with their children,” the shelter official told her. Ms. Chitam started calling around. She found a conference room, located 28 mats, and put the new arrivals up for the night. The next day a church opened up space for people to sleep.

“No one asks for a crisis,” says Ms. Chitam, a native of Zambia. “But it’s on our clock, on our watch.”

Activists and officials also are frustrated because the newcomers could help solve the state’s most looming problem – a labor shortage. Maine’s aging population is the oldest in the country, and the flight of younger people out of the state exacerbates job vacancies. But federal regulations do not allow asylum-seekers to work until their applications are heard, which often takes more than a year.

“This disconnection really drives us crazy,” says Mr. Jalali. “We are suffering from not having enough people to work. You have hundreds of able-bodied, motivated young people who are literally dying to work. ... And then we don’t let them.”

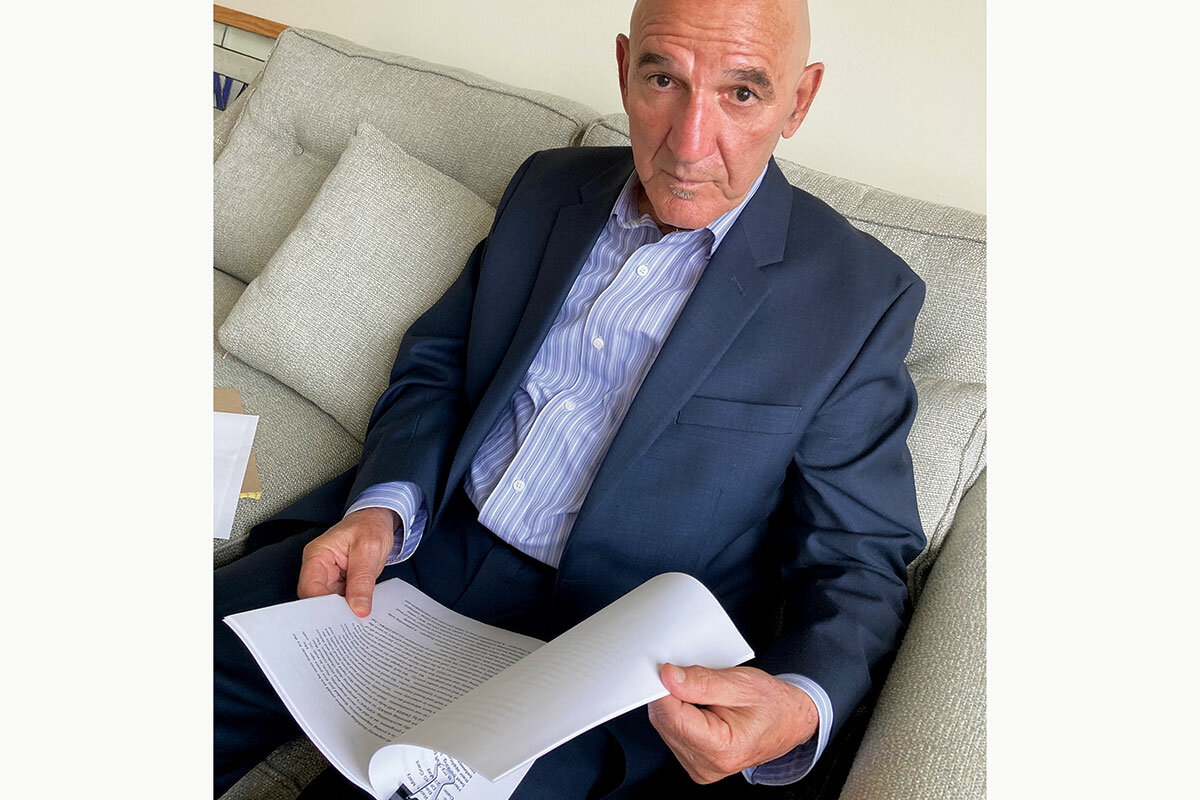

Nelson Tinti is one. He stays after one of Ms. Barker’s English classes, struggling to tell his story through the translator app on his phone. Worked 15 years in a bank in Angola ... married with two children ... joined protests against the government ... was beaten, ran, arrested, escaped.

Mr. Tinti scrolls through the timeline of photos on his cellphone, and points. There he is amid the smoke and violence of street protests. There is a dead protester sprawled on a sidewalk. There is the wailing mother of a slain child. He points to pictures of his friends. At image after image, he draws a finger across his throat to pantomime their fate. Each dead.

With his wife and two children, Mr. Tinti fled to Dubai, United Arab Emirates, and then to Houston, and then to Portland. For five months they have lived in one room in a motel.

“I have to put my family first. I have to learn English,” says Mr. Tinti. “I have to have a spot to live. If God allows me to continue here, I will stay here.”

Maine is the whitest state in the nation, with 94% of its population identifying as white. There is some racial frothing at the African arrivals on social media. But most pushback is framed in terms of the cost of services to newcomers at a time of inflation and rising expenses, says Ms. West, the city manager. “When you increase taxes, that’s really difficult for a lot of people in Portland to handle,” she says.

Just a block off the main street in downtown Portland, Lucie Narukundo presides over a tiny cramped grocery store into which she packs the bounty of Africa. “Here,” she says, plucking a bag of dried fish from a shelf. “Sardines from Tanzania and Burundi.” She hefts a bag of cassava flour from Congo. There is a tin of peanut powder and passion fruit from Rwanda. From Kenya she has spices, and prunes from Cameroon.

Women in bright floral dresses crowd into the store, and men linger to banter with the owner, who keeps order in 14 languages (“We moved around a lot,” she explains, understating a life spent fleeing wars throughout southern Africa.) Her daughter Nicole Iriza, who just graduated from Wheaton College with a degree in sociology, stops by. She may work for her mother, she says, adding with a sly laugh, “if she pays me enough.”

In one aisle, Paolina Mabiala, recently arrived from Angola, erupts in delight at finding an African snack called mabele – an edible clay. She rips open the bag and savors a piece. “I love this stuff!” she says in Portuguese.

Ms. Narukundo, a native of Congo, arrived as a refugee in 2010. She opened the Moriah Store in 2014 and is planning to expand.

The newcomers “have nothing,” Ms. Narukundo says. “But after a while they will get work permits and pay taxes. I am very happy to pay taxes. It is my contribution.”

The state wants the new arrivals, says Greg Payne, senior housing adviser to the governor. But the big problem is a long-festering shortage of affordable housing.

“I think we need to figure out, how do we moderate the pace of arrivals in a way that prevents it from becoming a humanitarian crisis when they arrive?” he says.

Mr. Payne notes that the state is reserving 100 rooms in a Comfort Inn in Saco, 16 miles south of Portland, to help ease the burden, and is moving to lease more affordable housing for two years. The state has also added $22 million for emergency housing in the budget.

City officials stridently resist the argument that their letters to groups along the southern U.S. border, saying there was “no more room,” is an attempt to close the doors of Portland.

“I don’t think that was the message,” says Belinda Ray, who works with the Greater Portland Council of Governments. “We’re spending ridiculous amounts of money to keep people in hotels,” not including food and the array of other services, she says. “It’s not sustainable.” The council is working with surrounding communities to find a more sustainable way to shelter asylum seekers.*

City officials want the state to take over the logistics crisis, knitting the disparate and overlapping local and nonprofit efforts into one coordinated approach, and to provide more housing. They also want the federal government to speed up the asylum process and allow arrivals to work.

But Mr. Strimling, the former mayor, says that’s not what the message from the city sounds like. “One of the things that I think has been great about Portland is that we’ve always said, ‘Our doors are open.’ And that was why so many were so disappointed by the letter from the city,” says Mr. Strimling.

“We have been a city of hope for new young families,” he adds. “And I think that’s vital to our future.”

Ms. Lafleur has hope. She left Haiti after the United Nations agency she worked for closed, and gangs in Haiti threatened her family. “Haiti is not a safe country,” she says through a Creole interpreter.

She flew to Chile, then took buses and boats before walking through Bolivia, Peru, and Panama. At one point, she had to traverse the fearsome Darién Gap jungle in Colombia and Panama. Crossing a fierce river, 12 of the 20 in her group were swept away, she says.

“The water was up to my chest. My husband carried my child on his neck, and he had to hold my hand. If he had not held me, I would have been sucked away.”

She squeezes her eyes shut as she recalls the pleas of her son to keep walking as they stumbled up and down treacherous mountains. “We can’t leave you behind,” the boy cried. Finally in Mexico, a taxi driver promised to take them to a crossing point, only to spirit them to an isolated place where they were robbed at gunpoint. They spent days in hiding. A police officer eventually offered to help, but he, too, wanted payment.

They finally contacted a cousin in the U.S., who scraped together enough money to put them on a bus to the border. Authorities let them cross into Texas, and “my husband heard of Catholic Charities in Portland,” she says. The family asked to be sent there.

Given her searing experiences, was it worth it all, to get to Portland? Ms. Lafleur’s somber face suddenly breaks into a dazzling smile.

“They take care of me here. They gave me food. They gave me a place, a motel room. Oh my God, I love it here. I will never leave.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify the goals of the the Greater Portland Council of Governments.