Can police police their own? NYPD as a case study.

Loading...

| New York

With some 36,000 officers, the New York Police Department is the largest police force in the world, and the most influential department in the country. In many respects, too, the NYPD has been the standard-bearer of tactical innovation and management reforms over the past three decades.

“The NYPD does kind of stand out as an exemplar among American police departments, specifically within the American policing community,” says Jorge Camacho, policy director of Yale Law School's Justice Collaboratory and a former Manhattan assistant district attorney. “By and large, NYPD officers are better trained than most officers in most other jurisdictions. They do have more oversight over them. Not to say that it’s perfect oversight. They just have more.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe NYPD has been the nation’s foremost laboratory of police reform. So as the country wrestles with how best to find ways forward on policing, New York stands out as a crucial case study.

But others see an inherent flaw: How can police, in effect, police themselves and punish their own? And is this a matter of “a few bad apples,” or are the current structures of police training and accountability deeply flawed?

For Samy Feliz and about 50 others gathered in front of City Hall, the NYPD’s tactical innovations and an astonishing drop in violent crime and police shootings have come with a terrible cost for the Black and Latino communities that have borne its relentless focus on high-crime neighborhoods: the number of young men, like Mr. Feliz’s brother, who have been shot and killed.

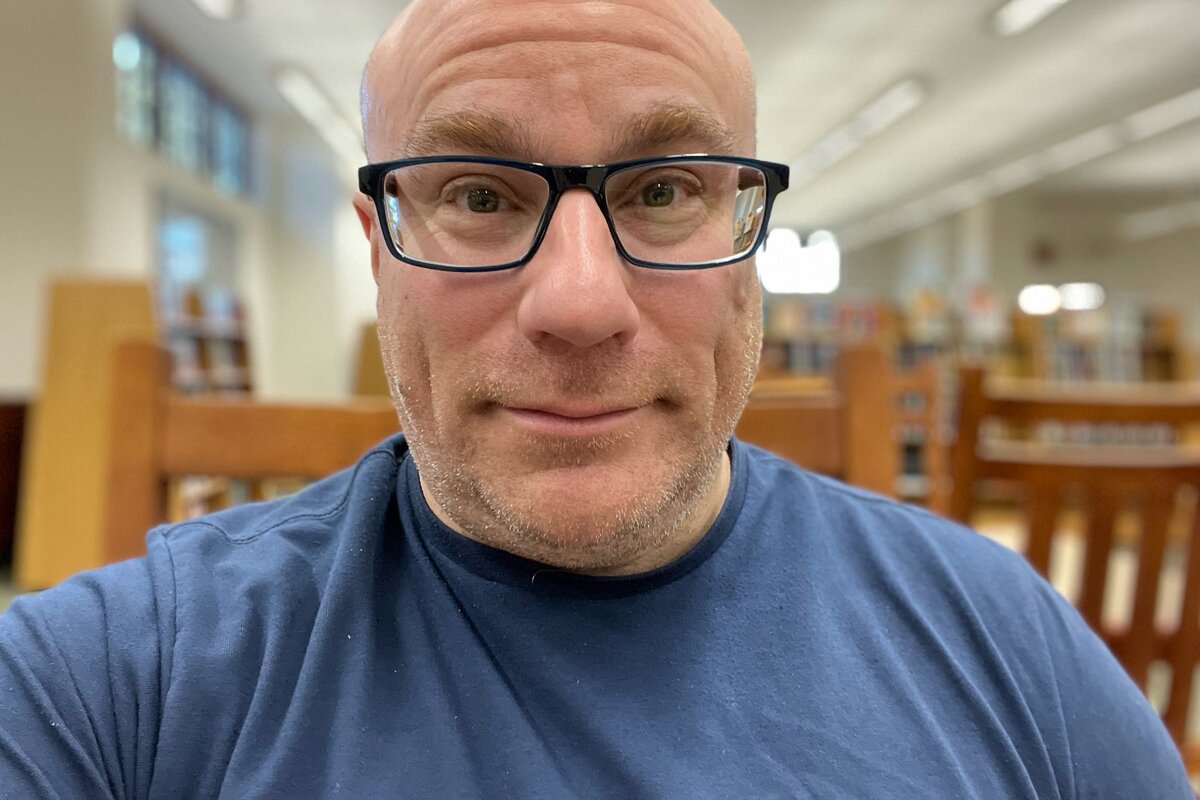

In 1994, when Joseph Giacalone was just two years and change on the job with the New York Police Department, he found himself in the middle of a shootout at a warehouse in the Bronx.

It would be the first and only time he’d fire his gun at a suspect.

After a decorated, two-decade career, the experience in that warehouse continues to shape his understanding of the issues surrounding police reform. That’s especially true, he says, after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 and the killing of Tyre Nichols at the hands of five Memphis police officers in January.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe NYPD has been the nation’s foremost laboratory of police reform. So as the country wrestles with how best to find ways forward on policing, New York stands out as a crucial case study.

Wielding the power of the state and given the duty to enforce its laws, police officers have a responsibility like few others in society, he says. It’s one of the reasons he now teaches his students the fundamentals of criminal investigation and the use of force, emphasizing the importance of training, professionalism, and accountability.

“When I look at the Derek Chauvin case [in Minneapolis], and now looking at the Memphis videos, the first thing that stands clear in my mind is: no supervision,” says Mr. Giacalone, now an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “There’s no supervisor on the scene in either case. Now, would a supervisor have prevented this? I believe so, because something went inherently wrong with these individuals.”

“And I would say none of it had to do with their training, because no one is trained to do the things they did,” he says. “It’s about supervision. It’s about accountability.”

With some 36,000 officers, the NYPD is the largest police force in the world, and the most influential department in the United States. In many respects, too, the NYPD has been the standard-bearer of tactical innovation and management reforms over the past three decades. It has been the nation’s foremost laboratory of police reform. So as the country wrestles with how best to find ways forward on policing, New York stands out as a crucial case study. To understand the past 30 years is to begin to understand how policing has gone right and how it has gone wrong.

“The NYPD does kind of stand out as an exemplar among American police departments, specifically within the American policing community,” says Jorge Camacho, policy director of the Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School and a former assistant district attorney in Manhattan. “By and large, NYPD officers are better trained than most officers in most other jurisdictions. They do have more oversight over them. Not to say that it’s perfect oversight. They just have more.”

When it comes to the reform of American policing, however, the idea of accountability remains one of the most bitterly contested. Mr. Giacalone and other experts see it as an essential value of management and professionalism.

But others see an inherent flaw – one that, at its worst, leads to the killing of Americans. How can police, in effect, police themselves and punish their own? And is this a matter of “a few bad apples,” or are the current structures of police training and accountability deeply flawed?

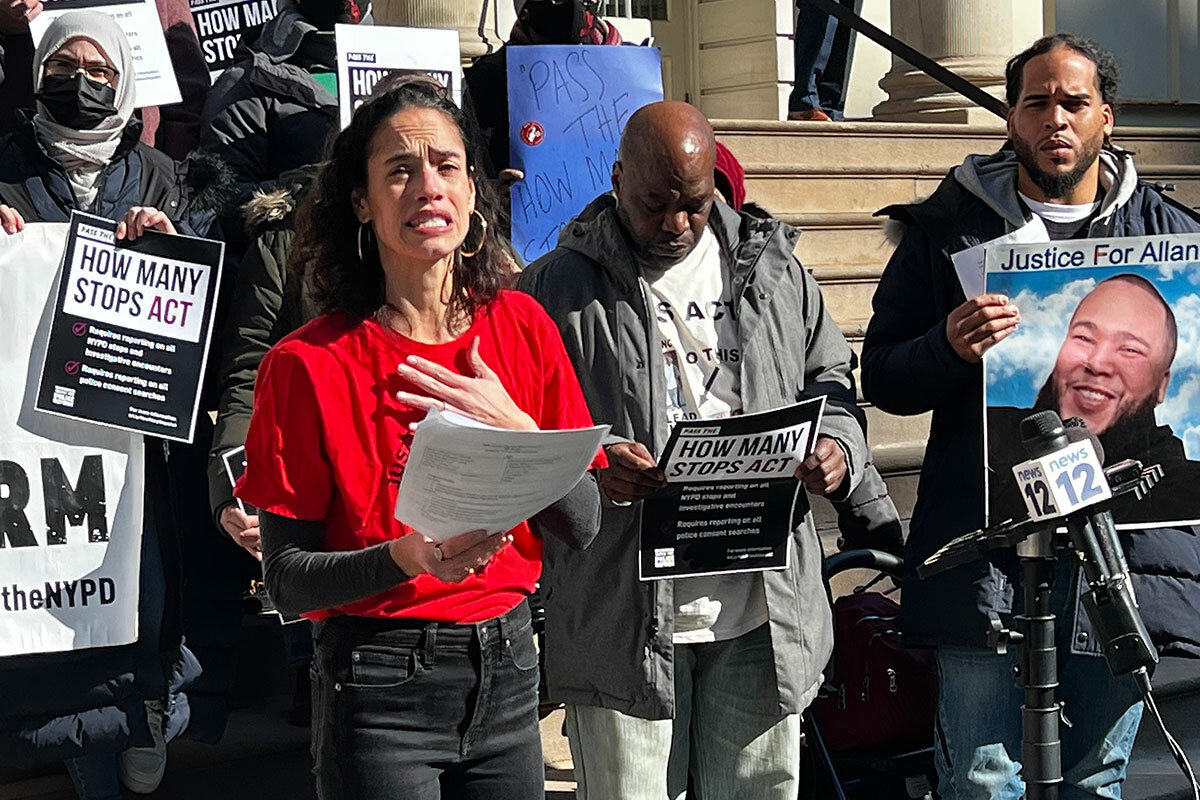

“We’ve seen time and time again how routine police stops have ended tragically,” says Alexa Avilés, a member of the New York City Council, speaking at a rally in front of City Hall calling for the NYPD to provide more data about its day-to-day methods and interactions with people on the street. “When is enough ever going to be enough? ... We want to know, with taxpayer dollars, are they doing the job that we are trusting them to do in the public?”

Councilwoman Avilés’ call for rigorous public transparency includes a fundamental opposition to one of the NYPD’s paradigm-shifting tactical innovations, begun 30 years ago: the relentless and data-driven focus on the city’s most crime-ridden neighborhoods.

Mr. Giacalone’s career with the NYPD, most of which he served as a supervising sergeant, spanned that era. In the early 1990s, when he was a rookie cop, the “mean streets” era of New York was reaching its ignominious peak: There were around 2,000 murders each year, and violent crime and armed robberies were reaching all-time highs.

The year he fired his weapon at a suspect was also one of the most transformative years in the history of the NYPD – and perhaps in the history of American policing. In 1994, the NYPD launched CompStat, short for “comparison statistics,” and started to pioneer the methods of data-driven policing.

It was also the time when the department began to reorganize the kinds of special anti-crime teams that would influence those like Memphis’s now-disbanded SCORPION unit. Instead of solving crimes that already happened, police would work to prevent them. Using techniques like stop and frisk, traffic stops, and minor violations like loitering and littering, the department would focus laserlike on getting illegal guns off the streets.

Mr. Giacalone says it was also around that time that the NYPD began to revamp its own systems of accountability, including for officer-involved shootings, which were happening hundreds of times per year. In the early 1970s, officers discharged their firearms almost 1,000 times annually.

In 1994, when Mr. Giacalone fired his .38 revolver at a suspect, it was one of 331 officer-involved shootings, according to NYPD data. That year, some 29 people were killed.

He and his partner responded to a report of a disturbance at a Bronx warehouse. An armed robbery was in progress: A crew from Brooklyn was attempting a heist of cable boxes.

“When we walked into the door of the place – it was into, like, a garage area – there was a break from the sun into this dark garage, so it took a second for your eyes to kind of adjust,” says Mr. Giacalone, who was responsible for the actions of 10 officers under him during his years as a sergeant. “But there was a guy with a gun, tying someone’s arms,” he says. The suspect immediately started shooting at them.

Mr. Giacalone says his NYPD training immediately kicked in. “Cover and concealment is something ingrained in your head, so that when you hear shots, you react,” he says. “You don’t even think about it.” He and his partner both dived behind a nearby van and returned fire. Then they “waited for the cavalry to arrive,” he says.

In the end, no one was shot or injured. Specialized units arrived, including hostage negotiators and canine units, and the suspects surrendered. They were eventually convicted and sent to prison.

Officers put their lives on the line every day, he says. Any routine call can suddenly turn into a life-or-death situation, a fact that makes policing a different kind of profession.

But 1994 was also the year in which crime began to fall dramatically, beginning what criminologists call “the great crime decline” of the past three decades. Murders in New York City fell from a peak of 2,262 in 1990 to just 292 in 2017, the fewest in the city’s history and an astonishing 88% drop. Since then the number of murders in NYC jumped to 438 in 2022 – a record short-term increase, but still 80% lower than in the early 1990s.

The number of officer-involved shootings also fell dramatically. In 2017, on-duty NYPD officers discharged their firearms 37 times, killing nine people. In 2022, there were 48 police shootings, in which 11 people lost their lives.

After he fired his gun, Mr. Giacalone immediately entered what could be called a protocol of accountability. Internal Affairs officers took his .38 revolver and inspected it. He and his partner were informed of their rights under General Order 15, a kind of Miranda rights for police, which gives them 48 hours to consult with an attorney before giving a statement.

“We didn’t need a lawyer, as far as I was concerned,” says Mr. Giacalone. “We had a union delegate there, and we just told our story.”

In early February, Samy Feliz stands in front of New York’s City Hall, demanding accountability for the NYPD officers who shot and killed his brother 3 1/2 years ago.

His brother, Allan Feliz, had been pulled over during a routine traffic stop in Washington Heights for what police say was a failure to wear a seat belt – a fact the Feliz family and its lawyer dispute after analyzing the three videos of the shooting, including police body camera footage and a bystander video.

The passengers in the car can be heard saying they were wearing seat belts. When the officers ran his brother’s ID, they found he had three outstanding warrants for tickets, including one for littering.

According to the videos, an altercation ensued, and police shocked Mr. Feliz’s brother with a stun gun. As one officer struggled with him in the front seat, the father of a 6-month-old can be heard yelling, “Don’t shoot me, don’t shoot me!” During the struggle, the car moved forward slowly, and then backward. Police say the brother, who served five years in prison for burglary, was trying to get away. The family says it was the police who caused the car to move during the struggle. One of the officers, a supervising sergeant, then fatally shot Mr. Feliz in the chest. As officers dragged him feet-first from the car, his pants and underwear were pulled down.

“This kind of disrespect and violence is the rule, not the exception,” says Samy Feliz, holding a picture of his brother in front of him as he recounts how Allan was shot and killed in the middle of an October afternoon, just as schools were letting out. Officers “yanked his body out of the car, exposing his genitals and leaving him, at 3 in the afternoon, for the world to see – kids walking home from school.”

For Mr. Feliz and about 50 others who have gathered in front of City Hall, the NYPD’s tactical innovations and the astonishing drop in violent crime and police shootings in New York have come with a terrible cost for the Black and Latino communities that have borne its relentless focus on high-crime neighborhoods: the number of young men who have been shot and killed.

“The vast majority of the time it’s just a few horrific stories of police killings that make it into the news,” says Gabby Cuesta, a leader in a coalition of civic groups and family members of those killed by police called Citizens United for Police Reform. “What this fails to show is that police killings are just the tip of the iceberg. ... [There are] thousands of examples of daily violence experienced by members of Black, Latinx, and other communities of color in New York City because of constant, disparate low-level enforcement and broken-windows policing that does not keep us safe.”

In some ways, the genesis of the coalition was after the fatal shooting of Amadou Diallo in 1999. A cadre of plainclothes officers called the Street Crime Unit, whose stated motto was “We own the night,” approached the student from Guinea, who was returning to his apartment in the early morning hours. When Mr. Diallo reached for his wallet, the four officers opened fire, shooting 41 rounds, 19 of which struck and killed the 23-year-old immigrant.

The NYPD did not discipline the officers, and they were acquitted of murder. But the department disbanded the unit.

It was in many ways the first of what became a national focus on police shootings. At the same time, however, activists and others began to scrutinize the NYPD’s tactics, including its growing emphasis on stops and frisks.

In 2001, the City Council passed legislation requiring the NYPD to provide its data on these stops – which proved to be one of the most momentous reforms for police accountability. The department’s own data revealed that police were stopping hundreds of thousands people each year, and about 85% were Black and Latino men. All it took was a “furtive glance” to justify a body search.

In 2012, groups that were part of the Citizens United for Police Reform coalition filed a successful lawsuit against the NYPD. In 2014, a federal judge ruled the NYPD’s stop and frisk practices violated the Constitution, illegally profiling people of color and violating the standards for “reasonable suspicion,” the threshold for conducting a search. The judge placed the NYPD under a federal monitorship, which continues today.

“While that was a huge win after years and years of organizing, the abuse continues,” says Samah Sisay, staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, which filed the successful federal lawsuit. “We know stop and frisk is still a reality in the city and the ways implemented? What we saw in the racial disparities that continue, are causing immense harm.”

In 2021, there were almost 9,000 stops and frisks, according to NYPD data, and 87% were of Black or Latino people.

The purpose of the rally in front of City Hall, in fact, was to call for passage of the How Many Stops Act, which would require the NYPD to provide the same kind of data for lower-level stops, including searches with consent. Data like this helped prove that the NYPD’s practices were unconstitutional, so activists hope to use it to continue to expose what is happening in their communities.

“These bills are going to bring critical and urgent transparency to the NYPD daily activities in our community,” says Ms. Cuesta. “Right now, the NYPD is only required to report on what we know as stop and frisk. That leaves the vast majority of encounters unreported.”

Community members, too, are concerned that Mayor Eric Adams has relaunched the kind of street crime units of the past as the city is experiencing a record increase in violent crime coming out of the pandemic.

After the Memphis Police Department disbanded its SCORPION unit after the killing of Mr. Nichols, Mr. Adams defended the efficacy of the technique, and the kinds of reforms the NYPD has put in place.

Now known as the Neighborhood Safety Teams, they are not completely a plainclothes unit, but wear identifying markings. Mayor Adams has touted its new methods of training, including de-escalation techniques, robust oversight, and a selection of officers who will not, he’s said, perpetuate “the abuses that we witnessed in the past.”

“Many people stated that we should not do it, but we were able to remove 7,000 guns off our streets; that’s a 27-year high,” he told CNN. “A combination of body camera footage is crucial, having the right supervision there, that can immediately de-escalate the situation or stop when it gets out of hand, and pick the right officers assigned. Just because you are a police officer does not mean that you are capable of doing every aspect of policing.”

The department also now provides a public database that allows users to view the records of NYPD misconduct allegations. Activists won another major victory for transparency in 2020 after New York repealed its Civil Rights Law 50-a, which long shielded the disciplinary records of NYPD officers from public view.

Mike Hayes, an investigative journalist who has long had “an obsession with disciplinary records,” remains skeptical. He says the administration of the database is “half-baked,” noting that a number of officer records he’s obtained are missing from the database.

“When the mayor talks about how last year the NYPD pulled 7,000 guns off the street, that is something that should absolutely be commended and is definitely a stat that you like to see,” says Mr. Hayes, author of “The Secret Files: Bill de Blasio, the NYPD, and the Broken Promises of Police Reform.”

“But I’ll push back on that and say, ‘Tell us how many of these guns were taken off the street by Neighborhood Safety Teams officers. Where are they operating?’” he says. “And as we sit here today, we don’t know who these officers are. That information has not been put out there in a very transparent way.”

Mr. Feliz, whose family has filed a wrongful death suit against the NYPD and is still waiting for the findings of the Citizens Complaint Review Board, says he continues to be profiled in his neighborhood and stopped by police for no reason.

“I can be waiting for a table outside of a restaurant, and I have a Neighborhood Safety Team officer asking me, ‘What’s going on? What are you doing?’” he says. “They asked me if I had anything on me, so I allowed them to conduct their search. Why? Because the entire time I’m having this experience with this officer, he has his hands on his holster and his gun like John Wayne.”

“That’s an intimidation tactic; that’s a coercion for me to allow him to check me,” Mr. Feliz continues, describing the kinds of lower-level stops that are not currently part of the public record. “That’s not anything that makes me as a New Yorker feel safe or reassured. ... It’s not a problem with ‘a few bad apples’; it’s a systematic lack of transparency and accountability.”

Editor’s note: The number of murders in New York City in 2022 has been corrected. There were 438.