Why a conservative Florida county raised taxes to help children

Loading...

| Pensacola, Fla.

Raising taxes in Escambia County, Florida, is “just about the worst thing that you could try,” says local hotelier Julian MacQueen. “It’s just a bad idea.”

Deeply conservative Escambia County has not traditionally been friendly to new government initiatives or taxes. But the county was failing its children, “our children,” says Mr. MacQueen, no fan of big government himself.

Why We Wrote This

The creation of the Escambia Children’s Trust in Pensacola, Florida, is part of a broader push to re-imagine the way American society values, understands, and helps children.

From abuse to income inequality and homelessness, young people in the area ranked below those in most other Florida counties. The difference was particularly pronounced for the county’s Black children, 39% of whom lived in poverty.

So during the same election that saw the county overwhelmingly support Donald Trump, citizens also voted to raise taxes to create the Escambia Children’s Trust, a new government agency to receive and distribute taxpayer dollars for the benefit of kids, and coordinate with a slew of existing nonprofit organizations and government entities. The vote to establish the Children’s Trust in Escambia County made this Panhandle community the first Republican municipality to join what has become a nationwide drive to rethink the way local communities support children.

“We’re trailblazing here,” says Kimberly Krupa, who lobbied for the Children’s Trust. “I hope we can be a model for other superconservative communities for how to do this.”

In the months leading up to the 2020 election, hotelier and philanthropist Julian MacQueen, usually a booster for this Florida Panhandle beach destination, found himself making an unusual pitch to the other business leaders of Pensacola.

Escambia County, he told them, was failing its children.

In all sorts of metrics of well-being, from abuse and mental health challenges to income inequality and homelessness, young people in their area ranked below those in most other Florida counties. The difference was particularly pronounced for the county’s Black children, 39% of whom lived in poverty, compared with 13% of white children.

Why We Wrote This

The creation of the Escambia Children’s Trust in Pensacola, Florida, is part of a broader push to re-imagine the way American society values, understands, and helps children.

Mr. MacQueen acknowledged that these numbers reflected a complex knot of economic, moral, and racial challenges. They were the sort of interconnected problems faced by millions of children across the country – struggles highlighted recently by the U.S. surgeon general’s office, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other groups. In report after report, these organizations have described how multiple pressures, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, have created a mental health crisis for children and families, one that is on regular display in Escambia County.

But Mr. MacQueen saw a way that his hometown could start fixing these problems. The rub, he explained to his business colleagues, was that it involved voters agreeing to increase taxes.

He still laughs thinking about it.

“Raising taxes in Escambia County is just about the worst thing that you could try,” he says. “It’s just a bad idea.”

That may be an understatement. Escambia County is not just Republican, but overwhelmingly supportive of former President Donald Trump. A Florida county on the edge of Alabama that leans Deep South in both history and politics, it has not traditionally been friendly to new government initiatives, taxes, or even explicit activism around racial disparity. Mr. MacQueen himself has donated to Republican campaigns and is no advocate of big government.

But with a small increase in property taxes, Mr. MacQueen explained to his friends, Escambia County could create a new entity called a children’s services council. This would be a new government agency that could receive and distribute taxpayer dollars for the benefit of kids, and coordinate a slew of nonprofit organizations, foundations, and government entities all working for the benefit of local children.

Supporting this tax, he argued, would be a vote for efficiency, problem-solving, and an investment in the Escambia County workforce of the future. And more importantly, he argued, it was the right thing to do for “our kids.”

That November, people in Escambia County voted overwhelmingly for Mr. Trump – and overwhelmingly, by 61%, to levy a new property tax and create the Escambia Children’s Trust.

“The story here is that regardless of your political focus, people fundamentally care about kids in this community,” Mr. MacQueen says.

But the story is something more, as well.

The vote to establish the Children’s Trust in Escambia County made this Panhandle community the first Republican municipality to join what has become a nationwide drive to rethink the way local communities support children, organizers say. It is part of a wider movement that is calling attention to what many have called a “crisis of childhood” in the United States, and it is on the front edges of re-imagining the way American society values, understands, and tries to help children.

It is also an example of a community taking the first steps to look squarely at economic and racial disparity, and trying – in whatever flawed, contentious, and human way – to creatively work for justice.

“We’re really a grand experiment,” says Kimberly Krupa, the former director of Achieve Escambia, the group that helped propose and lobby for the Children’s Trust. “We’re trailblazing here. I hope we can be a model for other superconservative communities for how to do this.”

For Asiah Lucas, this sort of help and coordination can’t come quickly enough. A single mother of a 4-year-old daughter, Zaquoia Hosea, Ms. Lucas works one job at an Escambia County call center, and a second job as a cashier at Whataburger, a Southern fast-food restaurant. It’s important for her to have these jobs, she says, even beyond the income. She believes they send a clear message to her daughter.

“I want her to have the world,” Ms. Lucas says. “I need to let her know that school and work are important.”

But these days, she says, it feels like she’s working just to work. The Head Start program where she sends Zaquoia just told parents it needed to cancel its 4-6 p.m. extended day session because it hasn’t been able to hire staff. This means that Ms. Lucas has to either find a babysitter or leave her shift early. Between that expense and rising gas prices, she’s close to losing money just going to work.

Misi Birdsall, director of Head Start and Early Head Start in Escambia County, sighs when she hears this. “I knew it would be hard for parents,” she says.

There are around 70 children in her program who, like Zaquoia, are going to lose extended day help, Ms. Birdsall says. But it’s been nearly impossible to attract teaching assistants at the $12 an hour that her budget allows, especially with chain stores and other local businesses offering pandemic raises and signing bonuses.

“The workforce issues are huge,” she says. “Teacher shortages have been going on for a while.”

And it’s not just impacting extended day. Ms. Birdsall has been trying for months to find an additional two dozen teachers and teaching assistants to run her regular school programs. Because of the shortage she hasn’t been able to open all her classrooms, where low-income children from birth to age 5 go for day care, preschool instruction, and healthy meals.

This means some 400 children are on the waitlist for Head Start in Escambia County, says Douglas Brown, executive director of the Community Action Program Committee, which administers Head Start in the region along with numerous other poverty-reduction programs. The gap in quality child care for low-income parents affects not only kids’ well-being, but their families as well, who often find themselves, like Ms. Lucas, with impossible choices.

“You’ve got folks that are in challenging circumstances economically,” Mr. Brown says. “And then you’ve got the pressures that come with the pandemic. The pressures of inflation that’s being pushed by global concerns. Gas prices. There are rising utility rates here. And then child care? People are feeling the pinch – where is this all going to come from?”

These are the sort of intertwined pressures Mr. Brown hopes the Children’s Trust might start to address – and the type that were the focus of a U.S. surgeon general’s warning about children’s mental health, released late last year. “The challenges today’s generation of young people face are unprecedented and uniquely hard to navigate,” wrote Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, who listed everything from income inequality and technology to racial injustice and gun violence as factors that have negatively impacted American children’s wellness, even before the pandemic.

Indeed, in 2020, UNICEF issued a report on the well-being of children in the world’s 29 richest countries, evaluating factors such as education, housing, health, and overall life satisfaction. The U.S. came in near the bottom in every category, ending up at 26th overall.

And all of this comes out in mental health, Dr. Murthy wrote. The proportion of high school students who reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased 40% from 2009 to 2019. Between 2011 and 2015, youth psychiatric visits to emergency departments for depression, anxiety, and behavioral challenges increased by 28%. And suicide rates increased among young people ages 10-24 by 57% between 2007 and 2018.

How the pandemic has altered all this is still up for debate. Emergency room visits for suspected suicide attempts increased substantially for adolescent girls – up some 51% in early 2021 compared with the same time period in 2019 – but other statistics show those numbers evening out over the course of the pandemic. While there has been anecdotal reporting about misbehavior in school and children suffering acute stress, other research shows children overall weathering the pandemic with remarkable resilience – often better than adults.

But focusing on these pandemic statistics in some ways misses the point.

“Even before the pandemic we were deeply concerned about the trajectory for kids on a number of fronts,” says Bruce Lesley, president of the child advocacy group First Focus on Children.

In other words, the pandemic did not cause many of the problems facing American children as much as it has revealed them, he and other advocates say. That is particularly true when it comes to racial disparities, such as those in Escambia County.

Indeed, Black Americans experienced a different pandemic than white Americans. Not only were children of color more likely to suffer serious illness, but they were also more likely to lose caregivers. According to the U.S. census, Black families struggled with disproportionate financial stress. Black families were also more likely to experience housing insecurity. In 2020, more than a quarter of Black children lived in poverty.

“It really shouldn’t be a surprise that so many young people are struggling, because what children see in the United States these days is a pretty hopeless picture,” says Jonathan Todres, a professor at Georgia State University College of Law who is an expert in children’s rights. “You have a pandemic that seemingly had no end in sight. ... You have gun violence, housing insecurity, and many other issues. And they also see adults, from policymakers in D.C. to school boards all around the country, arguing and finger-pointing and making little meaningful progress to help children.”

Part of the challenge, he and others say, is that it’s difficult to isolate the factors that affect children. Even those in advocacy roles often find themselves lobbying for individual bills, such as the child tax credit, instead of looking at the overall system of care, says Mr. Lesley. They also find themselves running into deep cultural beliefs about individualism and “parental deservedness” – the idea that children should only receive assistance if their parents “deserve” that expenditure, as opposed to treating children as individuals with their own needs and rights.

This has pushed some advocates to embrace a new, holistic approach to children’s issues, he says. Some are pushing for a federal children’s cabinet, a national children’s ombudsperson, or a wider adoption of a system of children’s rights. (The U.S. is the one country in the world that has not ratified the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, because of concerns of Republicans in the U.S. Senate that the treaty would undermine U.S. laws and families.)

And some have begun to turn away from the federal government altogether and focus instead on local jurisdictions, such as Escambia County, where they believe there is a better chance of coordinating different segments of government and civil society to make comprehensive changes for children.

“For the past 25 years, this hasn’t been a front-burner issue, to think about what’s happening with our kids,” says Elizabeth Gaines, founder of the Children’s Funding Project, an organization that works with local governments to understand money streams and data to coordinate strategic change for kids. “But now I think everybody knows and feels and understands the ‘whole child’ needs in a different way.”

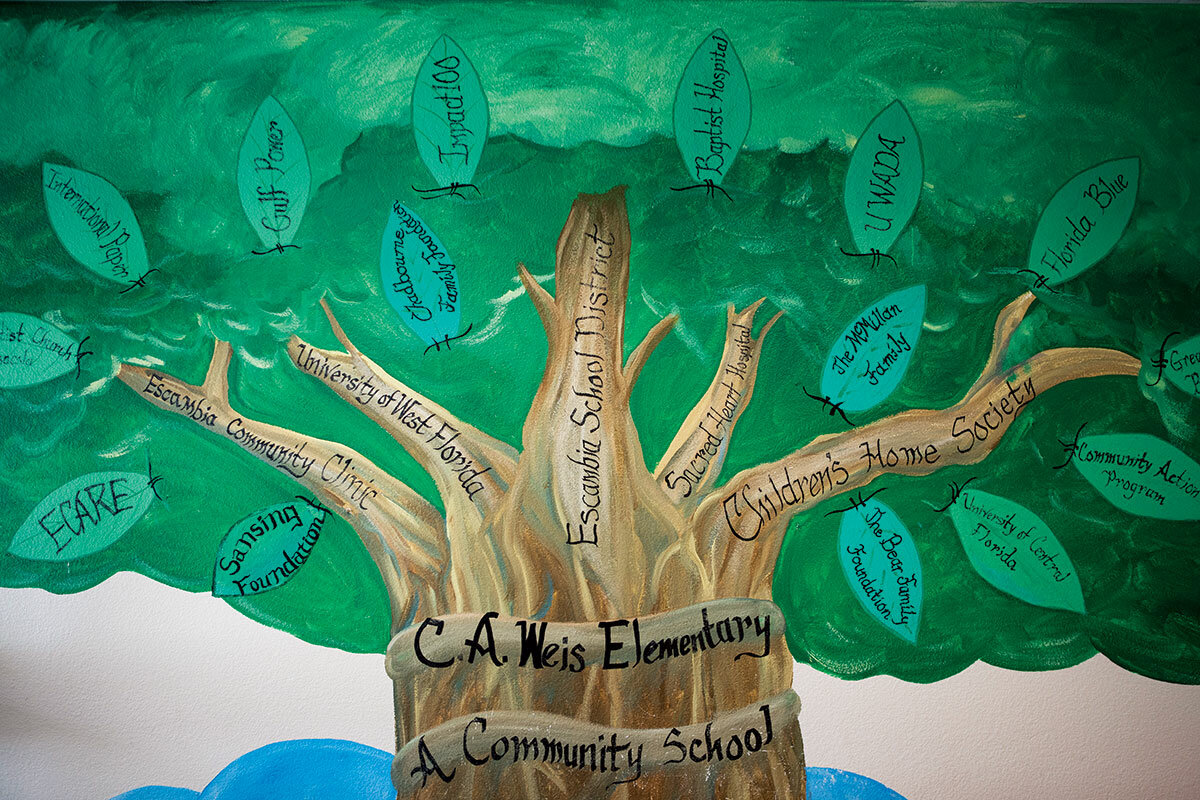

C.A. Weis Elementary School sits in one of the poorest ZIP codes in Florida, in a downtrodden neighborhood on the western side of Pensacola, a world away from the white sand beaches of the Gulf Coast. Yet the school shows what can happen when different types of organizations focused on children start to work together. And it is a model, says Dr. Krupa, the former Achieve Escambia director, of what the county wants to do on a larger scale with the new Children’s Trust.

Weis is a “community partnership school,” a Florida example of a district combining forces with a host of other groups – medical providers, nonprofits, local colleges – to give students and families wraparound care at one site. At the elementary school here that means everything from social workers and mental health counselors to food and housing assistance for families, a pediatric clinic, GED classes for parents, and free uniforms. A dental clinic provides regular checkups, and all the students at the school get vision screenings and glasses if they need them.

The partnership is about seven years into 25 years’ worth of funding – a long enough runway, supporters say, for real change to take place.

“This is the model,” says principal Kimberly Thomas. “I am a huge advocate. ... The classroom teachers can focus on the teaching and learning because they know that there are other resources to help with the social, the emotional, the basic needs of a student that are not oftentimes found in schools.”

Teachers who recognize that a student doesn’t have clean clothing, or who learn that a parent has lost housing, can ask their nonprofit partner, Children’s Home Society, to fix the issue. And every two years, explains Lindsey Cannon, executive director of the northwest Florida branch of the Children’s Home Society, the partners survey children’s families and those who live in the school district to learn what needs they see as most pressing.

Most recently, residents said they wanted a safe place for children to play and easily accessible medical care. The partners worked to let neighbors know about the pediatric clinic they have on-site, and Ms. Cannon began raising money to renovate the school’s playground – not only for students, but also for neighbors to use as a local park on weekends.

“Everything we’ve done here, and the way that we’ve done it, has been driven by what the community told us they needed,” Ms. Cannon says.

One recent afternoon, dozens of education undergraduates from the University of West Florida in Pensacola tutor Weis students in reading, while parents file into a classroom to work on their GED studies. Down the hall, students Candace Bell and Nehemiah McCullough work with a fourth grade teacher on a science project, wrestling with how to inflate a balloon without blowing air into it themselves.

“I like learning new things every day,” Candace says. “I get to be with my friends and be with awesome teachers.”

Nehemiah is also a fan of the school – but his favorite part is the counselor he sees.

“It helps me,” he says softly. “She gives me snacks and she helps me with my anger.”

Weis is what’s known as a Title I school – its entire student body qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch under federal poverty guidelines. And while it still lags behind wealthier school districts in test scores, it has improved under this community care model, from a failing grade to a C.

Dr. Thomas would like to do better, but she is more focused on measuring each student’s individual growth. And that has shown noticeable improvement, even during the pandemic.

Recently, she’s noticed yet another trend: Children who move away, or who live in other neighborhoods, are increasingly trying to “choice” into, get assigned to Weis, something unheard of a decade earlier.

Tori Woods hopes the new Escambia Children’s Trust will build this sort of collaboration to help even more young people – young people who are struggling with some of the same issues she faced growing up here.

She is one of 10 trust board members, half of whom are gubernatorial appointees. She is also a Black woman who remembers being one of the handful of Black students in her elementary school, all of whom lived on her grandmother’s street. When she went to high school, she says, she was one of two Black students in her advanced classes.

“It was a good old boy system,” she recalls. “I didn’t feel that there were a lot of resources for people who looked like me.”

For some years, she says, she stayed away from Pensacola. But eventually a combination of work and her husband’s family led to a return. It didn’t go well at first. Her daughter, then in 10th grade, struggled, and suffered from what her mother describes as intense bullying.

Ms. Woods decided to join the local Parent Teacher Association to try to better advocate for her daughter. It was the beginning of a deepening involvement in working for local children. She says she needed to become the kind of activist that she never had in school.

“A lot of the children who will need [the trust’s] resources are being raised by women of color,” says Ms. Woods. “I have to be the squeaky wheel.”

Children’s trusts or councils now exist in 11 states. Florida, with 10, has more than any other state, all of which are supported by taxpayer dollars. Some are relatively new, while others, such as the Children’s Services Council of Broward County, have been in existence for years.

Those with a longer track record have data that show a clear improvement in children’s well-being – something that convinced Mr. MacQueen and others that this was the right way to try to coordinate care in Escambia County, despite concern from some in the community that raising taxes and putting more government money toward complicated problems wouldn’t help.

“I am just hoping this bridges the gap for families,” Ms. Woods says. “We have to level the playing field.”

Still, she knows it will take time to get the trust up and running. At a recent board meeting, she listens as Tammy Greer, the trust’s new executive director, presents some of the first steps she hopes the organization will take to determine how to disperse its funds. Alongside her in the city council room sit others on the trust’s board of directors – a circuit court judge, an adoption lawyer, and school board representatives. It has already become clear, local child advocates say, that these board members have different ideas on how best to focus and coordinate care. But this, they add, is part of the process. The important step is that they are doing it at all.

“It’s hard and long to do, but we’re not going to get it done any different way,” says Ms. Gaines of the Children’s Funding Project. “There is a local movement building – that piece is really important.”