On a Montana mountaintop, this lookout watches for fire – and hope

Loading...

| Patrol Mountain, Mont.

For the past 26 wildfire seasons, since the age of 21, Samsara Duffey has served as a fire lookout on Patrol Mountain in Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness.

Her decades of solo bushwhacking trips across ridges and drainages are legendary here and have resulted in intimate knowledge of her fire district that allows her to isolate smoke quickly and report flames with pinpoint accuracy.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWith snowpack shrinking and wildfires growing more frequent, climate change can stir panic. But this veteran fire lookout has a fresh and calm perspective, informed by her joy, hope, and experience in the wilderness.

Despite having been on watch as the West experiences the engulfing effects of climate change – fires growing more frequent and burning hotter, fire seasons lengthening, and snowpack shrinking across the Rocky Mountains – Ms. Duffey continues to find hope in the natural world. She accepts what the seasons bring, and the shadow of climate change doesn’t darken her experience of the world she loves deeply.

“It contradicts with how I feel about the political situation of our country, and everything going on ecologically, but I still find daily joy,” she says peering out her window. “Three days ago, that flower wasn’t there,” she says pointing to the snowfield on the lee side of the ridge. “Now all of a sudden there’s a blossom. That’s amazing.”

“Once I start to hear the lightning rods buzz, I have to get back inside,” Samsara Duffey warns as she watches black clouds advance from the southwest toward this windswept 8,000-foot peak. “Sometimes the hair on my forehead will tickle [with electricity]. That’s when I know I better find cover.”

A moment later, the air vibrates, and a static hum reaches her ears. Sheets of gray rain across the upper South Fork of the Sun River advance toward Ms. Duffey’s 1962 U.S. Forest Service lookout building here in “The Bob” – Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness. Her border collie, Mae, leads the way up the steps and through the tattered screen door.

The southeast wind picks up and finds the cracks between the wood and 107 windowpanes. Each fragile piece was carried on a mule up the winding 6-mile trail from the valley. The radio sputters with trail crews checking in.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWith snowpack shrinking and wildfires growing more frequent, climate change can stir panic. But this veteran fire lookout has a fresh and calm perspective, informed by her joy, hope, and experience in the wilderness.

“The cabin shakes when the wind hits 25 miles per hour,” she says, leaning against the shuttering western wall. “I think I can feel it coming.”

As the room darkens beneath the clouds, her grin anticipates the collision between the storm and her shelter, giving away her comfort with wilderness extremity.

For the past 26 wildfire seasons, since the age of 21, Ms. Duffey has served as a fire lookout for the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. Decades of legendary solo bushwhacking trips across ridges and drainages have resulted in intimate knowledge of her fire district and beyond. This “ground truthing” helps her pinpoint smoke and flames with acute accuracy.

After watching the American West burn summer after summer from her perch above tree line, she’s developed a complex view of environmental responsibility, informed by a palpable joy in the wilderness and ethical introspection on the interactions between the human and nonhuman

world.

“This place has a value in and of itself without humans. The intrinsic value of wilderness is wilderness,” she says. “My duty is to try to interpret, report, and provide experiences for people where they understand that. And beyond that privilege is the joy of getting up every day and looking at this landscape.”

The sweep of that terrain comes into sharp focus as the battering gusts and fat rain on the trembling windows let up after only half an hour. As the storm rolls east out of the mountains and onto the prairie, the strobe of cloud-to-cloud lightning above Haystack Butte brightens its dramatic pinnacle and steep sides for an instant.

It started with a grizzly encounter

Bears padded quietly across the forest floor near a tent where a 16-year-old Samsara and her mother slept. The two had backpacked into Indian Point in The Bob the day before and hung their food packs high in the trees after dinner.

“We didn’t know when we arrived, but there were habituated grizzly bears in the area,” the fire spotter today explains, noting that the bears had become accustomed to humans and their food. The commotion of the bears discovering their packs woke mother and daughter, but in the dark night neither of them could see the animals. Morning light revealed their supplies strewn across the pine needles, torn by teeth and claws.

“They were so comfortable around humans, the Fish, Wildlife, and Parks killed the sow, and the cubs were sent to a zoo in Little Rock, Arkansas,” says Ms. Duffey.

That incident shaped her sense of responsibility for her impact on the natural world: “I felt it was my fault,” she says, her voice cracking. “And so, a lot of what I’ve done through my work is to try to keep that from happening.”

Spurred by her commitment to wild places and creatures, and hoping to prevent more human-animal conflict, she majored in wildlife management at the University of Alaska Fairbanks after high school in Helena, Montana. A few semesters into her studies, she realized that the science of wildlife management – “the counting and counting” – didn’t interest her, but she still earned her bachelor’s in wildlife biology. The ethics of how the human and nonhuman world interact grip her to this day.

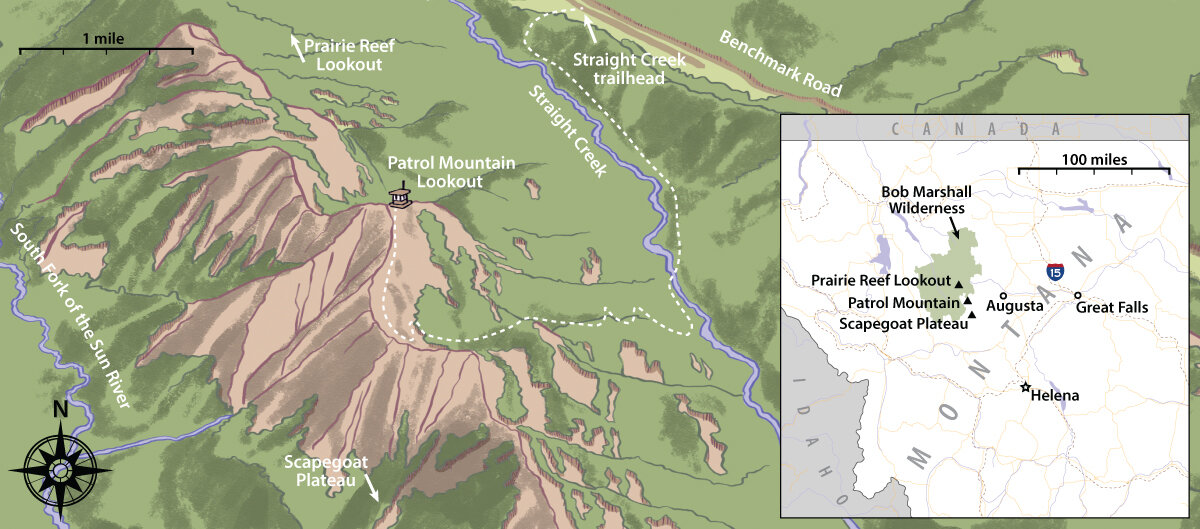

In 1997, home in Montana for the summer and searching for work, Ms. Duffey learned that the lookout job at Patrol was open. With her sister located at the Prairie Reef lookout 12 miles (as the crow flies) from Patrol, she jumped at the opportunity.

While not the highest peak in the range, the mountain still offers an expansive view of the U.S. Forest Service’s 1,200-square-mile fire district – an area the size of Rhode Island. The view of the land she’s responsible for in the Patrol district, and beyond, is carved and buckled by Straight Creek and the South Fork of the Sun River drainages, Sugarloaf Mountain, Scapegoat Plateau, and countless limestone cliffs.

Yet even these sweeping vistas aren’t temptation enough to draw many hikers up the trail to the lookout – on average 60 to 80 a summer sign Ms. Duffey’s guest book at the summit. In just 6 miles, from the Straight Creek trailhead on the dirt Benchmark Road, the path ascends nearly 3,000 vertical feet and includes a slick-stoned creek crossing that runs cold with snowmelt. It’s also her only maintained route to civilization.

This unique summer job was federally established more than six decades before Ms. Duffey was born. A series of rampant fires burned 3 million acres in Montana, Idaho, and Washington in 1910. “The Great Fire,” as it was called, sparked the Forest Service to prioritize fire detection in protecting the nation’s natural resources.

Lookout towers were built across the country, and by the 1940s, around 5,000 fire lookouts stewarded the national forests. However, most of those posts have closed due to advances in technology such as planes and satellite imaging. The Forest Fire Lookout Association estimates around 400 fire lookouts are still operational today.

Ms. Duffey’s 12 weeks of work fall roughly between July 1 and Sept. 20 every year. The four-days-on, three-days-off rotation consists of 10-hour shifts when she monitors trail crews, fields questions from the Forest Service in Great Falls, and scans the expansive landscape for smoke. On the days she turns the radio off, Ms. Duffey explores the wilderness just off the steps of her wooden cabin.

Priceless ground truth

The gurgling summer flows of the South Fork of the Sun River were interrupted by the jingling straps and buckles of a pack train headed into the backcountry over a decade ago. Montana writer Hal Herring had moved to the Rocky Mountain Front only a few years prior and was still learning the lay of land. Accompanied by some friends, Mr. Herring was bound for the White River, deep in The Bob. Their mules were loaded with a week’s worth of camping supplies tucked in panniers. A sharp bend in the trail revealed a woman drinking water in a snowberry patch, her running shorts and shoes out of place on a remote path on which most people are burdened by backpacks and boots.

“The people I was with knew her, so they all said hello,” says Mr. Herring, who waved as he passed. “I asked them at our next break, ‘Who was that in the shorts?’”

“Samsara, the Patrol Mountain lookout,” his companions chorused, explaining that on her days off, she sometimes runs to a neighboring lookout at Prairie Reef to visit.

“I turned and couldn’t even see Patrol from where we were,” Mr. Herring laughs. “I asked the party, ‘Isn’t that really far?’”

“Not for her,” they replied.

Ms. Duffey has an extraordinary ability to read the land and feels comfortable exploring off trail.

“I see a mountain, ridge, or basin I want to reach, and I just hike. Used to run more,” she laughs. “There doesn’t necessarily need to be a trail. I used to look at a lot of topographic maps, but now I know the landscape well. If I really need to make time, more than 20 miles in a day, I’ll stick to the trail. But when I’m exploring, I’ll take old, no longer maintained trails or animal paths.”

Unless she’s hiking through a recent burn, Ms. Duffey negotiates forests littered with blowdown – dead trees toppled by wind that make walking more like climbing through a jungle gym. Lodgepole pines are notorious for remaining flexible after death, and their sharp branches catch skin and clothing as a hiker scrambles over, under, and around. Even maintained trails have fallen trees, and because The Bob is federally designated wilderness, trail crews aren’t allowed to use chain saws to remove the fallen timber, resulting in slower clearing. Ms. Duffey has learned her landscape through blood, sweat, and worn-out shoes.

“It helps me know the place I’m responsible for,” she says. “All the hiking is for pleasure, but it helps me be better at my job.”

With this knowledge of “ground truthing” – providing direct observation on-site to confirm mapping images – she can isolate smoke quickly and report flames with familiar detail, which is invaluable to her supervisors in Great Falls.

“A fire lookout’s knowledge and presence on the landscape is pretty priceless,” says Michael Kaiser, Helena district fire management officer. “They can guide folks into the fire they spotted either through trails, roads, or landscape features. And when they have eyes on the fire, they can provide updates to make sure folks on the ground don’t get into a bad situation.”

One such fire Ms. Duffey spotted in 2021 burned near Danaher Cabin, an 1800s homestead now used as a Forest Service patrol station, which is beyond her district boundary. “Scrambling through that country helped me develop a feel for the distances when reporting the fire,” she explains, “and I could tell that the smoke was on the west side of the mountain coming from somewhere near the cabin.”

The “jolt” of recognition

The sky was empty except for drift smoke from far-off fires one summer day in 2019. Ms. Duffey sat at the radio knitting, not expecting any storms until later in the afternoon. Then, like a tulip unfurling in the morning, a thunderhead suddenly blossomed to the south. Without the warning of thunder, it dropped a single strike, then fizzled back into the blue not 10 minutes after it appeared. The spontaneous cloud left her delighted and awed at the dynamic nature of the sky she monitors.

“This is a good place to look at clouds,” she says.

In the mountains Ms. Duffey stewards, human-caused fires are rare due to the remote nature of the forest. Lightning strikes are the most common igniter, and knowing the different clouds helps her prepare for incoming weather and possible fires.

“When I see some wispy virga, that indicates strong winds up high. When I get completely overcast, it’s a midlevel stratocumulus, which is just a solid layer. And then there are the orographic or ground-effect clouds like lenticular clouds,” she explains, the scientific descriptions animating her face as she talks.

But what happens when the watching becomes witnessing – when her big sky reverie is interrupted by that plume of smoke she’s commissioned to look for.

“There’s a jolt,” she says.

“No matter how many I spot, there’s a similar rush every time,” she confesses. “And because of that initial rush, my first step is to grab my binoculars and make sure it is smoke. Even after 50-some fires, I’ll get excited over blowing pollen, which can mimic smoke. There’s another phenomenon right after a storm called ‘waterdogs’ that can look like smoke as well.”

Once smoke is confirmed, she uses her Osborne fire finder to pinpoint the location of the fire. Despite being developed in the early 20th century – the model in the Patrol lookout was made in 1934 and sports an updated map from 1967 – this technology is still one of the modern fire lookout’s most important tools.

Installed in the heart of the cabin, the fire finder is a map of the surrounding landscape with a hole at the epicenter marking the lookout. The map is bordered by a graduated measurement ring. And to determine the bearing of a fire, Ms. Duffey peers through a sighting hole on one side of the tool’s rim.

Using a welded handle on the measurement ring, she rotates her sight until it’s aligned with the wire crosshairs on the far side. The crosshairs must zero in on the smoke or flames. Then, using the map and her expertise of the landscape she’s watched and walked, Ms. Duffey can estimate roughly how far away the fire is from the lookout. The heading to the smoke is called an azimuth, the horizontal angle or direction of a compass bearing.

She then fills out a smoke report, radios the dispatch operator in Great Falls, and continues to monitor the smoke.

“Once I call it in, everything is out of my hands. I’ll take note and be available,” she says of the surprisingly businesslike process that flows from the initial jolt of a fire.

Indeed, her decades of stewardship here have shaped her manner in both the short and long view: Ms. Duffey holds a calm and accepting attitude.

Despite having been on watch as the West experiences the engulfing effects of climate change – fires growing more frequent and burning hotter, fire seasons lengthening, and snowpack shrinking across the Rocky Mountains – Ms. Duffey continues to find hope in the natural world. She accepts what the seasons bring, but the shadow of climate change doesn’t darken her experience of the world she loves deeply.

“It contradicts with how I feel about the political situation of our country, and everything going on ecologically, but I still find daily joy,” she says peering out her window. “Three days ago, that flower wasn’t there”; she points to the snowfield on the lee side of the ridge. “Now all of a sudden there’s a blossom. That’s amazing.”

Her intimacy with the land results in an idiosyncratic perspective of the blazes she’s entrusted to spot.

“This is a fire-adapted landscape,” she explains. “There are plants and animals who need fire to come through this place. I report the fires, but I don’t feel as if I’m saving the trees when I call it in. They’ve burned before and will again.”

Do right by the deer and lichen

Because she can’t leave the mountain as easily as many Americans leave their workplace, she continues her responsibility to the mountains beyond her punched timecard.

“This is where I get to live and work,” says Ms. Duffey. “It’s a privilege to be here and work here. I love this landscape, and I want to do right by it.”

But, she clarifies, “this isn’t my home. It’s the deer’s, lichen’s, and eagle’s. I don’t want to cause any more harm than I have to.”

The way she mitigates her impact while she occupies the shelter displays her humility before the wilderness. She collects her plastic and organic trash – no bear attractants allowed outside the shelter – which must be carted off the mountain on the mule train that arrives to resupply her food and water every three weeks. All her paper and “dry” trash is burned in the wood stove just often enough “so it doesn’t get too stinky.”

Her ground toilet – “the out,” as she calls the open-air commode – offers a grandiose view northeast toward the Sun River, and with only one main user, the privy can naturally decompose all waste.

Once a week, she washes her hair and uses baby wipes for what she calls “spit baths.”

“I don’t know what it is,” she says with a chuckle over her isolation, “but for some reason, most people happen to show up while I’m taking a bath.”

The accrued quotidian experiences of her 26 summers here have given her an outlook and deep-rooted sense of place that she believes can inspire others – the visitors to her lookout, students in the classrooms where she substitute teaches in the winter, or people she leads on tours in Yellowstone National Park – to learn more about their homes.

“I think most people would struggle to name and identify their state tree,” she says, prefacing her conviction that the connection to nature is essential for everyone. “That’s something little, but it grows into the problem of people not being connected to where they live, which is why we have the idea that wilderness is not necessarily a good thing. The settlers that came to the United States believed that they had to subdue the wilderness. They were proud to cut their homes out of the woods, plow the fields, and dominate and subdue the landscape.”

While Ms. Duffey feels more comfortable in the crowd of ravens and ground squirrels here than in a busy bar, she says most people might perceive her as lonely.

That’s not how she sees herself: “There’s a difference between being lonely and being alone.”

“I mean there’s always Mae,” she laughs as the border collie opens her eyes from a nap. “But I see such incredible things when I’m alone. There are so few people who get to see wolverines. I was sitting out there on the Honeymoon Basin rim one day, quiet, and a wolverine walked within 30 steps of me. Didn’t even know I was there until I moved.”

She considers that the stillness and patience of being by oneself must be relearned in our increasingly connected and stimulated society. Those who separate willingly are often misunderstood.

“As children, we aren’t given the tools to learn how to be comfortable with ourselves,” she says. “Particularly girls and women who are always told that their value, safety, and happiness are based on men. We aren’t encouraged to develop introspection, critical thinking, or the ability to hang out by ourselves. When we spend that time alone, we receive the message back: Really? Are you OK?”

Even in her married life, Ms. Duffey must spend time alone. Her husband is a smokejumper supervisor in West Yellowstone, where they make their home. Their summers – a fire worker’s busiest time – are spent apart, with only infrequent texts sent between them. They try to spend at least one or two weekends together, but the 5-hour drive and 4-hour hike to her aerie make visits difficult.

“One time,” she reminisces with a smile, “he got to the trailhead at 10 p.m., and instead of sleeping in the car, he started up ... through the dark and got here after 2 a.m. He didn’t even have a headlamp.”

Conscious stewardship – 24/7

Beyond those special days, Ms. Duffey fills her time – when not operating the radio or actively looking for smoke – knitting or reading. Along the northern cabin wall, there’s a stuffed shelf that includes “Brave New World,” “Jane Eyre,” and “Of Mice and Men.”

But knitting is her most intensive and time-consuming creative outlet in the lookout, and the mules trekked an entire duffel bag of yarn up the mountain for her this summer. Her favorite patterns come from the Fair Isle of Scotland. Hats, gloves, and sweaters with complex color sequences adorn hooks in the lookout.

Even when her hands are working the knitting needles and her mind is focused on the design, her eyes wander across the panorama of mountains and valleys outside the windows, still stewarding from the mountain that has taught her the long view.

“I don’t feel lucky or unlucky if my district burns or doesn’t burn,” she says of nature’s course. “I have a good summer no matter what. I’m here to watch, and there’s always something to see.”