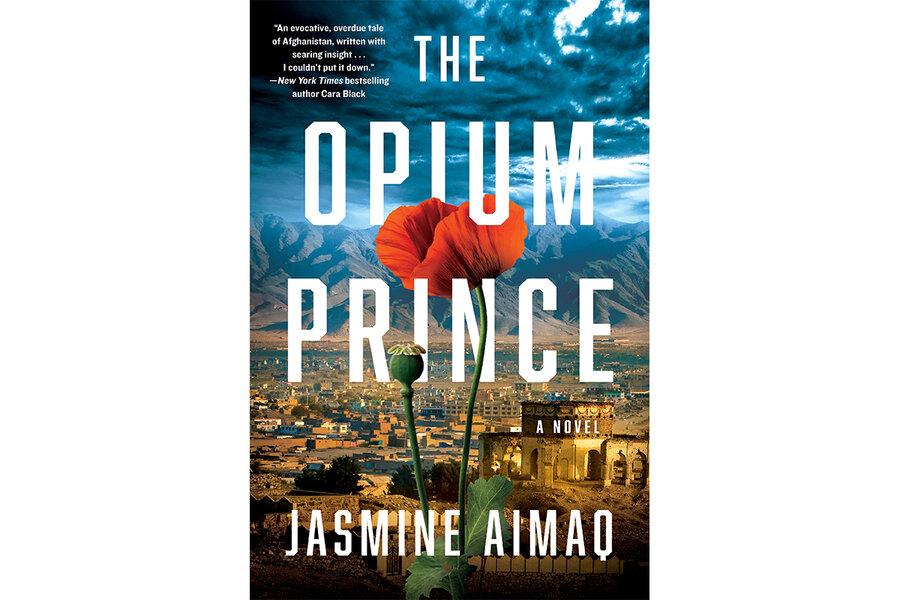

In ‘The Opium Prince,’ the personal plays out amid the political

Loading...

Jasmine Aimaq’s debut novel, “The Opium Prince,” is enjoyable on multiple levels. First, it’s a captivating work of fiction that examines how its two protagonists move from guilt and despair to redemption. Second, Aimaq immerses readers into everyday life in Afghanistan with such skill that even a passage about buying freshly baked flatbread is a poetic experience.

Set during the late 1970s, “The Opium Prince” is faithful to the historical events that rocked Afghanistan during the period. It’s also illustrative of the deep gap between the haves and the have-nots. And it provides a good example of what William Faulkner believed to be the goal of all authors and poets: to depict “the human heart in conflict with itself ... because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.”

As Daniel Sajadi and his American wife, Rebecca, are driving out from Kabul on an anniversary trip, he accidently hits and kills a Kochi girl named Telaya. In a tense confrontation with her parents and other members of the Kochi people, he is let off with a nominal fine. This is in part because, as nomads, the life of a Kochi – especially a young girl – is seen by Afghan authorities as having little value. But it’s also because a mysterious stranger named Taj Maleki intervenes.

Aimaq uses this confrontation to set up a contrapuntal narrative between the lives of Daniel and Taj. Daniel – the son of a deceased Afghan war hero and an American mother – is in Afghanistan as the head of a U.S. agency focused on eliminating the heroin-producing poppy fields. Taj, who began life as a nameless orphan, has become a wealthy opium khan whose very fields are the ones targeted by Daniel’s agency for destruction.

The main substance of the story centers around Taj’s attempts to manipulate and profit from Daniel’s deep guilt over the accident. Add to this a troubled marriage, jealousy over real or imagined past affairs, and an unflinching look at all the strata of Afghan society and you have a story that holds the reader’s attention.

International politics are woven throughout the narrative. While one man is tasked with enforcing America’s war on drugs, another seeks to protect his opium-based income through blackmail and intimidation. Beneath the plot, Aimaq lays out a series of rhetorical questions: Is the war on drugs doomed to failure because so many people (like the nomadic Kochi) must produce them to earn an income? Do the chemicals used to eradicate the poppies cause lingering health problems? Can farmers really make a decent income by growing something other than opium poppies? Is the Western world hypocritical by trying to eliminate the drug, while at the same time being one of its key markets?

Aimaq also has a keen grasp of social settings and the psychological interplay that takes place during conversations. At a party at the Sajadi’s, “Rebecca dropped a James Brown record on the turntable. The ambassador gave her a peck on the cheek. ‘How’s my fastest typist tonight?’ She hugged him halfheartedly, like he was a toy she had outgrown, and when she walked away, she curled her fingers into her palms.”

Aimaq’s novel also chronicles the collapse of the Afghan government, from the assassination of President Mohammed Daoud Khan to the communist political party that replaced him in a coup. Against this real-life backdrop, the fates of the main protagonists play out almost in the tradition of classic Greek tragedy. Yet the end is not so formulaic; as the plot evolves, an unforeseen transformation takes place.

Aimaq herself is Afghan-Swedish, and growing up in Afghanistan has allowed her to write about the people of that country with authority and clarity. Readers will come away with a deeper understanding of the land and its inhabitants, and will also have reason to anticipate her next literary effort.