In Latin America, women code a better future

Loading...

As a young woman growing up in a shantytown in Lima, Peru, the idea of earning more money in a single paycheck than her family saw in months, maybe years, would’ve been laughable. But 17-year-old Mirella Acelo is learning computer coding and is on her way to a well-paid career.

Every day, Mirella makes her way into the city as one of the select students at Laboratoria, a web development and coding academy for underprivileged women.

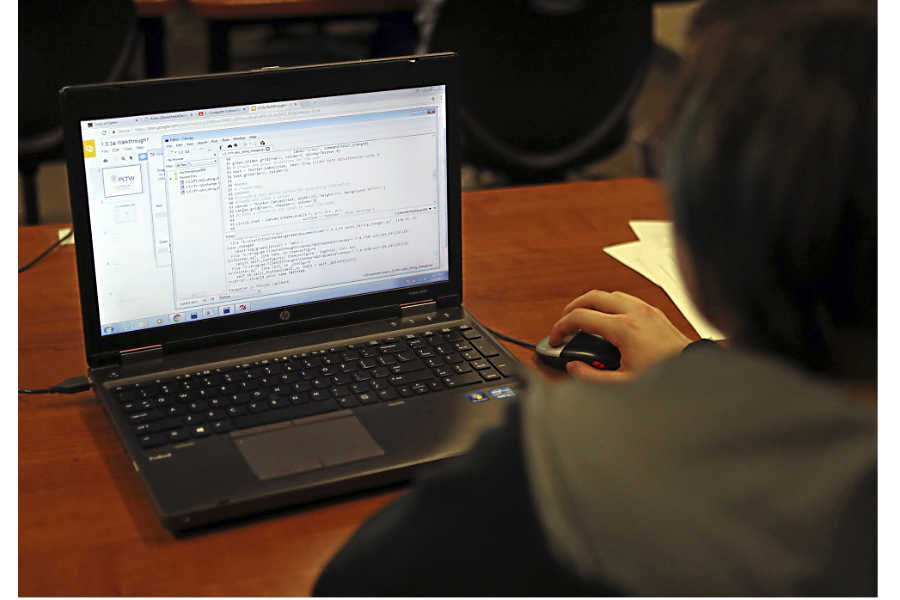

Mirella, like most of her peers at Laboratoria, couldn’t afford to attend college or university. While most of these students would otherwise be destined for low-wage jobs, they are instead seated in a high-rise among high-rises near the ocean, focusing intensely on their laptops. Each girl stares at a black box on her screen, working through a coding problem. Once they graduate, they are fed into a number of direct employment opportunities with Laboratoria’s ever-expanding tech partners.

Laboratoria started in Lima as the brainchild of Peruvian Mariana Costa (recently named one of BBC’s top 100 most influential women), her husband Herman Marin, and her classmate Rodulfo Prieto. Costa studied abroad at the London School of Economics, and later received her Master in Public Administration in Development Practice degree from Columbia University’s School of International Affairs. Prieto, originally from Venezuela, also received his Master in Public Administration degree from Columbia.

Costa has a rich background in supporting social enterprises and education. While at Columbia she worked for Ankay, a non-profit that awards full scholarships to disadvantaged youth in Peru, as well as providing psychological and academic help throughout their university careers. Later, she worked for TechnoServe, another non-profit organization that guides people in developing countries out of poverty, by providing business solutions to help them build profitable farms, products, or companies.

The spark for Laboratoria came when Costa, Marin, and Prieto decided to start a business together, AYU. They knew they wanted to start a company that had a social impact. Marin was a software developer, so they decided to start a web development service for clients. But as they attempted to build a team of software developers, they discovered the pool of people with these skills was tiny.

The pool of women with coding skills was practically nonexistent.

Here was their chance for social impact. Almost a quarter of all Latin American youth – 22 million – are either unemployed or unable to attend school. Of those, 70 percent are girls. Without training or education, the likelihood of women elevating themselves out of poverty is almost impossible.

Costa counts herself lucky that she had more opportunities growing up than most. When people are blocked from entering employable fields due to economic or social barriers, she says, it’s society as a whole that suffers.

“There’s an increased awareness about the need to have diverse teams and also for women to take advantage of all the opportunities that tech represents,” Costa told The Guardian recently in Lima.

What started as a small pilot program with 15 students has grown to four training academies in Lima and Arequipa, Peru; Mexico City; and Santiago, Chile. Young women accepted into the program go through a technology boot camp, learning how to code and design web sites in six months. Laboratoria then dedicates another 18 months to training them for specific jobs.

The program is highly competitive. An applicant’s aptitude and willingness to learn can be a ticket in, rather than a particular level of education or social background. Those accepted have more than just their gender in common. They’ve grown up amid poverty, and also experienced familial and social obligations which have kept them from pursuing careers. This kind of shared experiences fosters a sense of solidarity and community.

Costa seeks applicants where other tech companies wouldn’t think to look. Girls and young women are the most vulnerable to poverty, but now have a fast track to change an otherwise stagnant economic trajectory. Costa intends to lead the tech industry in populating it with female Latin American coders.

“Laboratoria at its heart is about empowerment and transformation,” she says.

The tech industry is hungry for new software developers and people who know how to code, regardless of whether they have a university degree or not. Laboratoria receives funding from tech giants Google, Microsoft, and Lenovo, as well as MIT, AT&T, the Chilean government, and others.

Students are fully funded through these sources. Once hired in the tech industry, graduates contribute 10 percent of their salary to the program for two years.

The academy has a nearly 80 percent job placement rate for graduates. Google and Microsoft hire directly from the pool of Laboratoria graduates.

The Laboratoria students are up before dawn to catch buses into the city for their classes. They are driven by a hunger for a new life and, most importantly, control over their future. Jobs in the tech industry pay upwards of three times what an average job pays.

“Learning how to code is a superpower!” says 26-year-old graduate Marisol Carrillo. “Now I can imagine something and start to create it.”

• This article originally appeared at Global Envision, a blog published by Mercy Corps.