Russia and the NATO it didn’t want: A disaster, or ‘no problem’?

Loading...

| Moscow

Not so long ago, Russian diplomacy aimed to revise European security architecture to make Ukraine look more like the Finnish example of a buffer zone between East and West.

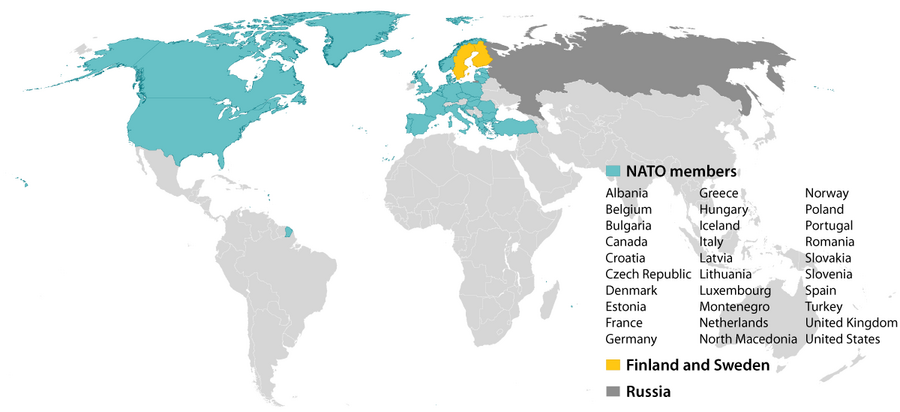

Now, the perennially neutral Nordic states of Finland and Sweden have reversed decades of policy and applied for membership in the NATO military alliance.

Why We Wrote This

Moscow views NATO expansion as a security threat. Now, thanks to its “special military operation” in Ukraine, Russia looks set to deal with the alliance along 800 more miles of its border.

Sweden and Finland have integrated with European institutions, including the EU, and hence the actual situation on the ground may not be practically affected by their impending NATO accession. Russian President Vladimir Putin suggested as much, recently arguing that there should be “no problem” as long as the new members of NATO refrain from basing foreign military infrastructure on their soil, especially nuclear weapons.

But it may not be so simple, Russian experts say. “My own view is that the situation is extremely unfavorable for Russia,” says Igor Korotchenko, editor of the National Defense journal. “Finland has a long frontier with Russia, and Russian forces in the western military district are currently insufficient to cover that. Sweden is a first-class military power, with a huge network of bases and airfields.”

Amid Russia’s aggressive actions in Ukraine, the perennially neutral Nordic states of Finland and Sweden have reversed decades of policy and applied for membership in the NATO military alliance.

For Moscow this is, at least on the symbolic level, a disaster.

Editor’s note: This article was edited in order to conform with Russian legislation criminalizing references to Russia’s current action in Ukraine as anything other than a “special military operation.”

Why We Wrote This

Moscow views NATO expansion as a security threat. Now, thanks to its “special military operation” in Ukraine, Russia looks set to deal with the alliance along 800 more miles of its border.

Not so long ago, Russian diplomacy aimed to revise European security architecture to make Ukraine look more like the Finnish example of a buffer zone between East and West. Now, with Finland ditching its neutrality to join NATO, even Kyiv has dropped talk it had earlier in the conflict of compromising on the issue of joining NATO. So profound is the geopolitical shift underway that Switzerland, which is often cited in dictionary definitions of “neutrality,” has indicated that it might revise its historical stance under the present circumstances.

Whatever the outcome of Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine, many analysts say Moscow faces decades of isolation in a Europe solidly united against it.

“If in the past there were reasons to speculate about a divergence between the [European Union] and NATO, now it looks like they go hand in hand, at least for the foreseeable future,” says Andrey Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “If [Russian President Vladimir] Putin’s idea was to put an end to NATO expansion, it clearly wasn’t very effective.”

A long frontier with Russia

After talking with Finnish President Sauli Niinistö recently, Mr. Putin surprised many by arguing that things needn’t be that bad. Indeed, he said, there should be “no problem,” as long as the new members of NATO refrain from basing foreign military infrastructure on their soil, especially nuclear weapons. Both Finland and Sweden have long been very capable exemplars of “armed neutrality,” maintaining de facto cooperation with the West in security and intelligence matters, and the actual military balance needn’t change, he suggested.

“Putin said that Russia doesn’t see any fresh threats, but will monitor the appearance of any new infrastructure and react accordingly,” says Igor Korotchenko, editor of the Moscow-based National Defense journal. “My own view is that the situation is extremely unfavorable for Russia. Finland has a long frontier with Russia, and Russian forces in the western military district are currently insufficient to cover that. Sweden is a first-class military power, with a huge network of bases and airfields.”

Sweden has been mostly neutral for over 200 years, even navigating World War II and the Cold War without changing its status.

Finland is a more complicated case. It was invaded by the USSR in 1939, and fought a bitter “Winter War,” which dealt severe damage to Soviet forces before Finland was compelled to cede territory. Defeated again in 1945, Finland adopted an official policy of non-alignment and spent the next several decades walking a careful foreign policy line between the USSR, later Russia, and the West.

In practice, however, Finland has integrated with European institutions, including the EU, and hence the actual situation on the ground may not be practically affected by its impending NATO accession.

Still, the geostrategic map is going to look radically different as Finland and Sweden move into NATO.

“The Baltic Sea will become, effectively, a NATO lake,” says Mr. Kortunov. “The border between Russia and NATO will basically double,” as Finland’s 800-mile frontier becomes, at least theoretically, a confrontation line. “In the Arctic Council, it will now be seven NATO members against Russia.”

It remains to be seen what model of NATO integration Finland and Sweden will adopt, Russian analysts say. Some northern European members of NATO, such as Norway and Iceland, eschew foreign bases on their territories, while others, like Poland and the Baltic states, enthusiastically embrace NATO deployments.

In a May 14 telephone conversation between Mr. Putin and Mr. Niinistö, the Russians may have been assured that Finland will take the former route, says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a leading Moscow-based foreign policy journal.

“Finland probably won’t want to host foreign military bases, much less nuclear weapons. So it’s possible that not much will have to change in practical terms,” he says.

“This issue of Ukraine is special”

Russian analysts say that the threat of Ukraine joining NATO posed a qualitatively different challenge for Moscow, paving the path to conflict, due to the country’s proximity to the Russian heartland, its big Russian-speaking population, and historical ties. Perhaps most importantly, the Kremlin has seen an aggressive nationalist threat in Ukraine since the 2014 Maidan revolution overthrew a Russia-friendly government and replaced it with a pro-Western one in Kyiv. Russia’s failure to secure Ukrainian neutrality is just one of the causes of the current crisis, they say.

“This issue of Ukraine is special,” says Mr. Lukyanov. “After all, Russia has accepted the entry of many others into NATO over the years. We may not have liked the idea of Poland, Estonia, Latvia, etc., joining the alliance, but it did not provoke war. It’s a similar situation with Finland and Sweden. This [war] is about Ukraine specifically.”

But some Russian officials claim that there is a wider, long-term scheme to isolate and undermine Russia now being brought to fruition. Ukraine was inducted into that plan following the Maidan revolution, offered political and military support and seduced with promises of NATO membership and European integration, they say, adding that the inevitable confrontation with Russia is currently being manipulated by Washington to achieve long-held strategic goals in Europe.

“The U.S. is using this Ukraine situation to expand its influence,” says Andrei Klimov, deputy chair of the International Affairs Committee of the Federation Council, Russia’s upper house of parliament. “It’s about much larger things than Ukraine. The U.S. has long wanted Finland and Sweden to abandon neutrality in order to master the Arctic. This is about the bigger picture, and the confrontation in Ukraine is just an instrument that is being exploited to the hilt.”