France’s textile capital tries eco-friendly fashion to get back in style

Loading...

| Tourcoing, France

For over a century, Hauts-de-France was the textile capital of France – until the jobs disappeared overseas. Today, it’s trying to reinvent itself as the country’s eco-friendly textile engine.

The push to reuse local materials and reduce waste is part of a larger phenomenon by French entrepreneurs to offer products that are made domestically. This past June, about 450 textile businesses joined forces to create the Textile Valley project, with the goal of bringing 1% of the country’s overall textile production back to Hauts-de-France, and with it, upwards of 4,000 jobs.

Why We Wrote This

Fashion-forward France wants to become a leader in eco-friendly clothing production. Part of that strategy is promoting items that are made locally.

Their hope is to revitalize communities, boost the local economy, and help consumers think differently about how they shop.

And since September 2020, the French government has plugged 100 billion euros into relaunching the economy, with a third dedicated to relocating production back to France using more modern, sustainable practices.

“French people like these products because they’re original, but also because they make a positive impact and have a history,” says Hubert Motte, founder of upcycle clothier La Vie est Belt. “Especially since COVID, there’s a desire by French people to leave ‘fast fashion’ behind and buy products that are made locally.”

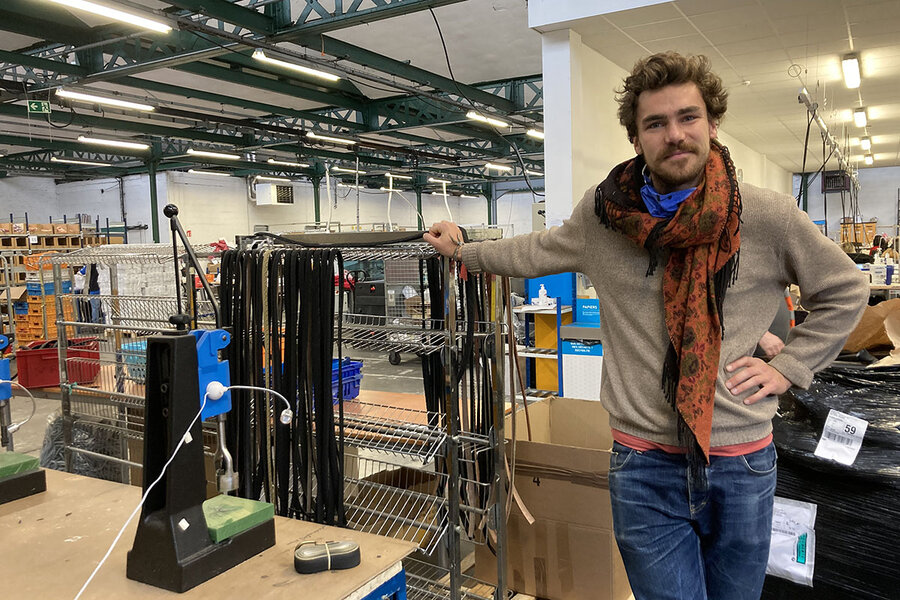

Strips of used, donated bicycle tires lie stacked in a pile on a flat work surface in a labyrinthine warehouse in this northern French town. Soon, the tires will be washed, perforated for buckles, and assembled into smart, sturdy belts.

They aren’t the only upcycled product created by La Vie est Belt. The textile company also takes used sheets to make men’s and women’s underwear, and even sells a DIY kit for customers to make their own undergarments.

“French people like these products because they’re original, but also because they make a positive impact and have a history,” says Hubert Motte, who founded La Vie est Belt in 2017 at the age of 23. “Especially since COVID, there’s a desire by French people to leave ‘fast fashion’ behind and buy products that are made locally.”

Why We Wrote This

Fashion-forward France wants to become a leader in eco-friendly clothing production. Part of that strategy is promoting items that are made locally.

In doing so, Mr. Motte and his company are helping turn this region into a textile-recycling engine at a time when both eco-friendly clothes and buy local movements are growing – the latter by as much as 64%, according to recent polls. The effort draws on the local history of Hauts-de-France’s history, which for over a century was the textile capital of France.

The push to reuse local materials and reduce waste is part of a larger phenomenon by French entrepreneurs to offer products that are made domestically. This past June, around 450 textile businesses joined forces to create the Textile Valley project, with the goal of bringing 1% of the country’s overall textile production back to Hauts-de-France, and with it, upwards of 4,000 jobs.

In an industry that destroys between 10,000 and 20,000 tons of products each year in France, textile producers in Hauts-de-France are now leading the country in creating eco-friendly, locally made clothing and accessories. Their hope is to revitalize communities, boost the local economy, and help consumers think differently about how they shop.

“French consumers are transforming how they buy clothing, leaning towards zero waste and buying less,” says Annick Jéhanne, president of Fashion Green Hub, a community of 300 businesses and collectives dedicated to sustainable fashion based in neighboring Roubaix. “But major labels need to make their clothing more sustainable and provide eco-friendly alternatives so that, ultimately, the consumer can make better choices.”

“Using these leftover fabrics just made sense”

France’s textile industry can be traced as far back as the 14th century to northern towns like Tourcoing and Roubaix, known primarily for production of wool and lace. After taking a hit following World War I and II, the industry began to prosper by the early 1950s, becoming the largest economic driver for the region.

But as businesses began outsourcing production to plants overseas, the industry saw a steady decline by the 1960s. And by the 21st century, local textile production had almost completely disappeared. Today, Hauts-de-France suffers from a lack of skilled textile workers as well as one of the highest levels of unemployment in the country.

Charles-Henri Florin, the owner of Peucelle & Florin, a Roubaix-based wool business in operation for a century, had a front-row seat to the region’s change in fortunes. The company got its start producing high-end wool for major labels. But instead of following its competitors, which were outsourcing to Asia in the 1960s, Peucelle & Florin decided to change its business model – looking to Italy to import quality recycled wool.

“That allowed us to weather the storm, and also keep production in Europe,” says Mr. Florin from his sprawling stockroom, which houses thousands of fabric samples. “It’s important to be transparent. Everyone is thinking about their environmental footprint these days.”

Mr. Florin passed on his savoir-faire and appreciation for sustainability to his daughter, Héloïse Grimonprez, who founded her clothing label Edie Grim in 2015. The two are now in partnership, with Ms. Grimonprez buying up Peucelle & Florin’s unused fabrics to create chic, tailor-made coats and blazers.

“When I started the company, no one was using terms like ‘eco-friendly,’” says Ms. Grimonprez. “But using these leftover fabrics just made sense. They were just sitting there and I thought, ‘I need to do something with this.’”

The growing desire to know the source of clothing is not just for the upwardly mobile and looks to be more than a passing trend. Mainstream brands are looking for ways to make their labels more eco-friendly as well, handing over part of production to the region. And since September 2020, the French government has plugged 100 billion euros into relaunching the economy, with a third dedicated to relocating production back to France using more modern, sustainable practices.

Roubaix-based national retailers are increasingly committing to better practices. Clothier Camaïeu sends the entirety of its unsold women’s clothing to a local workshop to be upcycled by women facing joblessness, and fashion retailer La Redoute is creating a 100% eco-friendly men’s line and aiming to produce zero carbon emissions by 2030.

“It’s not a question of being trendy”

France’s next generation of designers looks set to carry the “made in France” concept beyond the trends, too. ESMOD, a private fashion school with branches across France, recently challenged students to create an eco-friendly clothing line to be produced by a local retailer. And degree programs in textile production, like the recently launched EPICC school – aimed at young people facing school difficulties – offer hope for the future of the industry here.

Entire neighborhoods in Tourcoing and Roubaix are now dedicated to new textile designers and producers, and several initiatives are working to boost manufacturing while also fighting exclusion.

The Projet Resilience – a network of 60 textile producers – has worked with those facing social or economic marginalization since March 2020 to teach basic sewing. The Atelier Agile has similar goals but on a smaller scale, planning to train about 30 people starting in January to produce small clothing series for new labels and capsule collections. And La Vie est Belt employs those living with disabilities, in partnership with social inclusion group AlterEos.

“Professors are asking us more and more to think about sustainability in our creations,” says Dune Girardot, who started working at Edie Grim after graduating from ESMOD last year. “It’s not a question of being trendy. It’s because it’s important.”

There are obstacles yet to overcome. The textile industry here is still recovering from having sent production overseas – it lost 530,000 jobs between 2006 and 2015, according to The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. As the desire for products made in France increases, the region has struggled to meet demand – both in materials and manpower.

But that demand shows that things are improving.

“I’m on back order. I’m waiting for more donations to come in so I can make my belts,” says Mr. Motte of La Vie est Belt. “It shows that things are changing. There’s definitely an energy here.”