Russians vote Sunday. Why don’t dirty tricks dissuade the opposition?

Loading...

| ARKHANGELSK, Russia

Russia officially declares itself to be a democracy. Russian media covers the campaigns much as the Western press covers elections. And just about everyone agrees that the elections do matter.

But while 14 parties, covering a wide spectrum from left to right, will be competing for seats in Russia’s lower house of parliament in a Sept. 19 election, opposition parties are carefully managed by the Russian state. The gamut of “loyal opposition” parties is genuine, and much of the criticism expressed by them can be as biting as in any Western democracy. But via electoral controls, individual pressure on candidates, or political “dirty tricks,” the state keeps any party or candidate who becomes a significant threat to the ruling United Russia party from success at the polls.

Why We Wrote This

Why do opposition-minded Russians vote in the elections? Because despite the state's tight controls over parties and the dirty tricks of the ruling United Russia, voting can make a difference.

Still, opposition candidates believe running is worthwhile.

“Little by little, even small drops of water can wear down a stone,” says Oleg Mandrykin, a candidate for the liberal Yabloko party. “We do not need any more revolutions in this country. That leaves us only with gradual, democratic methods to bring about the changes we need. And we’ve seen some small, local victories that suggest it can happen.”

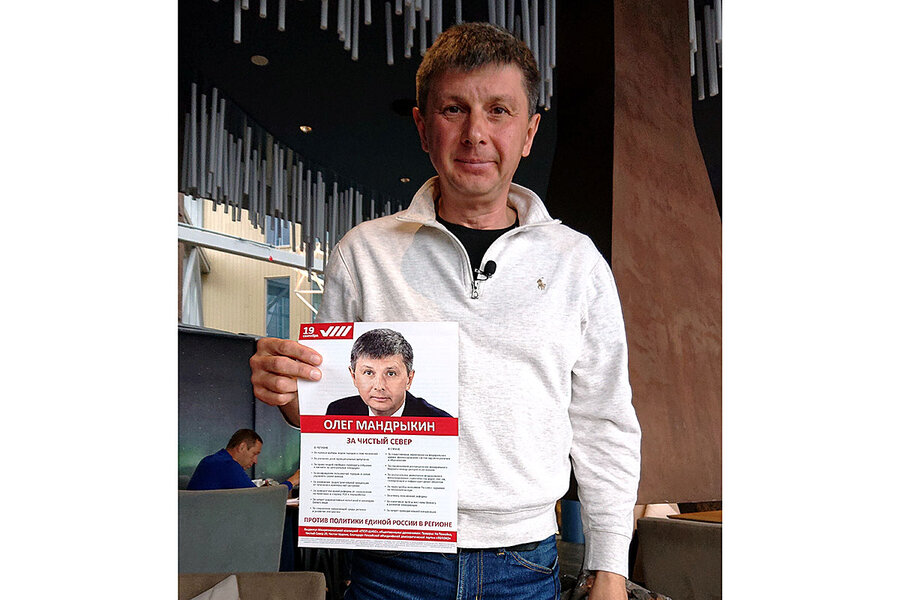

Oleg Mandrykin, who is running for a seat in the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament, believes that even Russia’s opaque, Kremlin-managed electoral system can be made to work in the interests of Russian voters if people get out and participate.

“Little by little, even small drops of water can wear down a stone,” says Mr. Mandrykin. “We do not need any more revolutions in this country. That leaves us only with gradual, democratic methods to bring about the changes we need. And we’ve seen some small, local victories that suggest it can happen.” That’s the optimistic side of the debate that breaks out whenever Russia holds an election, as it will be on Sept. 19 for the Duma and a multitude of regional and local legislatures.

Then he launches into the list of daunting obstacles he has faced, including official harassment because he is a candidate for the liberal opposition Yabloko party.

Why We Wrote This

Why do opposition-minded Russians vote in the elections? Because despite the state's tight controls over parties and the dirty tricks of the ruling United Russia, voting can make a difference.

Russia officially declares itself to be a democracy. Russian media covers the campaigning almost like a horse race, much as the Western press covers elections. And just about everyone agrees that the elections do matter, though opinions differ over the reasons.

But while 14 parties, covering a wide spectrum from left to right, will be competing for seats in the Duma, opposition parties are carefully watched and managed by the Russian state. The gamut of “loyal opposition” parties is genuine, and much of the criticism expressed by them can be as biting as the differences between candidates in any Western democracy. But via electoral controls, individual pressure on candidates, or simple political “dirty tricks,” the state keeps any party or candidate who becomes a significant threat to the ruling United Russia party from success at the polls.

This year, United Russia seems to be in particular trouble at the polls, which experts say could reflect badly on President Vladimir Putin, whom the party lines up behind. And they warn that could mean the opposition parties will be victim to even more electoral trickery this election.

“There are signs that the Kremlin is very nervous about the outcome of these elections,” says Masha Lipman, editor of Point & Counterpoint, a journal of Russian affairs published by George Washington University. “The so-called menu of manipulations is much broader than in the past. Even though Putin’s rating remains high, perhaps because he is seen as the guarantor of stability, United Russia is no longer regarded as a force for good.”

A controlled election

There are 450 Duma seats at stake in Sunday’s elections, half of which will be allotted by party line voting, the other half by 225 constituency races such as the one Mr. Mandrykin, a popular local environmental activist, is contesting in the Arctic region of Arkhangelsk. Six of the 14 parties competing – including the Communists, the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, and the social democratic Fair Russia party – got more than 5% of the vote in the polls five years ago, earning them seats in the Duma, so they expect at least to repeat their performance.

Proponents of the system say that it fulfills Russia’s need. “I think the existing electoral system reflects adequately the voter’s will,” says Viktor Kuznetsov, United Russia candidate in the central Russian region of Samara. The 14 parties running “actually represent the full spectrum of political forces in our society.”

Ms. Lipman says the Kremlin wants to be assured of a parliamentary majority for United Russia, to quell any disquiet among Russia’s notoriously fractious elites about Mr. Putin’s grip on the country. Some opinion polls suggest that United Russia’s current support could be as low as 27%, far down from the 54% it won in 2016.

“In Russia, an election campaign is a referendum on the president,” says Dmitry Oreshkin, an independent political observer. “If the voters’ support is strong, it means they trust a strong Putin. If not, it means Putin looks weak.”

In a show of just how important Russian elections can be, the Kremlin’s harshest critic, jailed anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny, has urged his followers to go to the polls. But he has called upon them to practice “smart voting”: concentrating votes behind any candidate from the approved “systemic opposition” who seems likely to defeat the official United Russia entry. His supporters have compiled a list of over 1,000 such candidates to back. Ironically, the majority of those are from the largest official opposition party, the Communists, who stand to benefit most from the backing of Mr. Navalny’s youthful and liberal followers.

That’s where the limitations on Russian democracy begin to become clear. The main reason Mr. Navalny must resort to throwing his weight behind candidates who are, basically, differing shades of pro-Kremlin, is that he and his millions of followers have been labeled “extremists” by the Russian government. They have been forced to disband their organizations and are banned from running in elections. Several other groups, mainly pro-Western liberals but also right-wing nationalists, have been similarly clipped from the permitted political spectrum.

“For those Russians who care about liberal ideas, democracy, and civil liberties, there are no candidates among the permitted parties running to represent them,” says Ms. Lipman. “The cutoff point for the Kremlin seems to be that nobody representing liberalism or Westernizing, modernizing ideas should be represented in the Duma.”

Barred candidates and dirty tricks

In addition to landscaping the political garden to weed out ideological threats, the Central Election Commission also employs a range of tools to bar individual candidates who are deemed insufficiently loyal or too popular. In the current election cycle, even the powerful Communist Party was compelled to drop Pavel Grudinin, one of its most appealing candidates and head of a prosperous collective farm near Moscow, after murky allegations were made about financial improprieties by his former wife.

Another sign of the Kremlin’s nervousness is the efforts by the state media watchdog, Roskomnadzor, to block Russian search engine Yandex from providing access to Mr. Navalny’s “smart voting” list of candidates.

Most experts say that actual vote-counting and polling station procedures on election day have been greatly cleaned up since obvious official voter fraud in the 2011 Duma elections triggered mass protests. But campaigning has been marked by dirty tricks, which critics insist are instigated by United Russia. They say the party uses its vast resources to manipulate the ballot, often employing smaller parties as its agents to make things difficult for strong Communist or Yabloko candidates. A pandemic-era ban on public meetings has made most open campaigning, formerly permitted, almost impossible for candidates from smaller parties.

A good example of dirty tricks is “doubling,” or getting a small party to run someone with the same name as a popular challenger. In St. Petersburg, two “Boris Vishnevsky” ballot entries, the result of two recent name changes accepted by the electoral authorities, suddenly appeared to run against the veteran Yabloko candidate Boris Vishnevsky.

“I don’t remember this kind of tactic being used before,” says Mr. Vishnevsky. “I was expecting more traditional methods to be used against me, like criminal charges or house arrest. Instead, these two guys, whose names were Shmelyov and Bykov until recently, are put on the ballot to confuse voters and take votes away from the dangerous candidate. It just means we have to try harder.”

Mr. Mandrykin, who was interviewed by the Monitor in late August, got a taste of poisoned media coverage when a local news agency, Ekho Severa, published what appear to be surveillance photos of the meeting, under the headline “Mandrykin, Who Do You Serve?” along with the suggestion – obvious but not explicit – that he discussed funding with a “foreign emissary.”

Reached for commentary, Ekho Severa Editor Ilya Azovskiy insists, “The word ‘emissary’ doesn’t have any negative meaning. Fred Weir, as a foreign journalist, is an emissary of a foreign state. We didn’t write directly that he financed Oleg Mandrykin’s campaign. ... I am sure that if I called up The Christian Science Monitor, they wouldn’t explain their editorial policy. So why should I?” (Editor’s note: Mark Sappenfield, the editor of The Christian Science Monitor, says, “The Monitor’s editorial policy is a matter of public record and a point of pride. We are eager to discuss it with anyone who has a genuine interest.”)

Given all that he’s had to go through, it might be hard to explain why Mr. Mandrykin even wants to run for the Duma.

“An elected deputy has the right to take the podium and to say what he thinks needs to be put on the record,” he says. “He or she has the right to meet with officials, ask questions, have input into the budget. Also the right to have 40 assistants, with a local office, and the right to meet with constituents, gather information, and respond to demands. If I get the chance, I will use these rights and make it matter.”