Moscow kids get teachers on screen, but trainees in class. Will it work?

Loading...

| Moscow

While Moscow schools have largely shut down as COVID-19 cases rise again, city officials have decreed that students in grades one to six need to have regular classes and daily face time with teachers. That has led to an unusual experiment in Moscow’s schools.

Healthy young volunteers have been recruited from Moscow’s several pedagogical colleges and universities, which train teachers, to act as in-class tutors. Meanwhile older and more vulnerable regular teachers deliver their lessons from the safety of their homes, displayed on a big computer screen at the front of the classroom.

Why We Wrote This

Amid the pandemic, how do schools balance educational needs of young students with the health of older teachers? In Moscow, the answer is to move the older teachers remote and bring teachers in training into the classroom.

“We know that many countries are in this situation, so we’re not the only ones facing this challenge,” says Sergei Graskin, a Moscow school principal. “It is of critical importance to protect our pupils and teaching staff in this pandemic. But we have to get the balance right.”

“The whole conservative model of teaching, where a teacher stands in front of a class and delivers a set amount of material and assigns huge amounts of homework, has been profoundly challenged,” says Alexander Adamsky, editor of an online journal of education. “A lot of problems have been exposed, but the system has also been forced to adopt some innovative new methods.”

All across Moscow, schools are mostly empty amid the city’s raging second wave of the coronavirus pandemic, as city government orders older pupils and staff to shelter at home and continue their studies online.

But, in a controversial move, Moscow officials have decreed that younger pupils cannot afford a repeat of the spring’s total lockdown. Rather, students in grades one to six need to have regular classes and daily face time with teachers.

That has led to an unusual experiment in Moscow’s schools.

Why We Wrote This

Amid the pandemic, how do schools balance educational needs of young students with the health of older teachers? In Moscow, the answer is to move the older teachers remote and bring teachers in training into the classroom.

Inside one of those – School No. 1580, a large, sprawling grade school that occupies most of a block in a leafy neighborhood in the center of the city – healthy young volunteers have been recruited from Moscow’s several pedagogical colleges and universities, which train teachers, to act as in-class tutors. Meanwhile older and more vulnerable regular teachers deliver their lessons from the safety of their homes, displayed on a big computer screen at the front of the classroom. A few senior students, nearing graduation, are even being handed full teaching responsibilities on a temporary basis.

“We know that many countries are in this situation, so we’re not the only ones facing this challenge. It is of critical importance to protect our pupils and teaching staff in this pandemic. But we have to get the balance right,” says Sergei Graskin, the school’s principal.

“Older pupils can study mostly online because they know how to use the technology and discipline themselves. This is not the case for the youngest ones. They absolutely need personal attention, to have their questions answered and be shown how to do things. It also seems that the younger children are the least vulnerable to this virus, and we have not been seeing many infections in our school,” he says.

Learning on the job

The scheme appears to be working well. In several classrooms, lessons are in full swing, with teachers delivering their material and handing out class work remotely, visible on a large screen. Meanwhile a masked student teacher hovers among the kids, directing their attention if it wanders, and later giving supplementary tutorials.

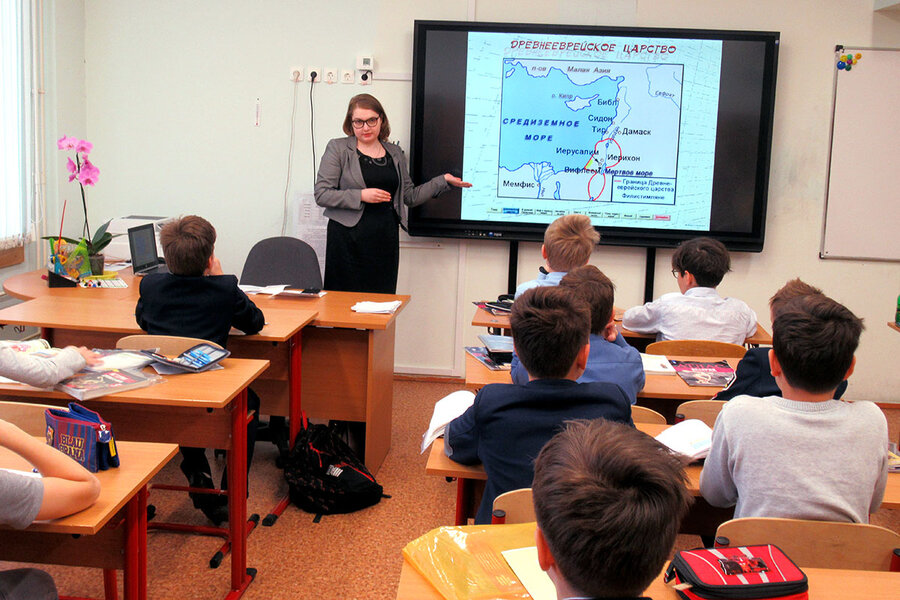

In one class, fifth-year pedagogical student Irina Vinogradova is teaching a history lesson on her own. She has a big, computerized diagram showing the world of the ancient Near East, and she’s explaining to the kids how civilizations interacted with each other in the past and continue to affect the present, spreading knowledge, technologies, and religions far beyond their own time and place.

She seems delighted with the opportunity to be a full teacher, even if unpaid and temporary. She has agreed to do it for one month, but that could be extended depending on the pandemic situation.

“This is so much better than regular practice teaching,” she says. “There is no teacher in the room, so I can try out the methods I’ve been learning, and get the full experience. I’m replacing an older teacher here, but at the same time I am continuing with my studies at the pedagogical institute. So, I am learning fast. I feel very comfortable with it. If I run into a problem, senior staff are being very helpful. And WhatsApp always works.”

Finding new ways to teach

In the Russian educational system, some schools orient on a particular specialization from the earliest grades. School 1580 has an engineering focus, and maintains a close relationship with Bauman State Technical University, which provides it with a lot of assistance and takes in many of its graduates. Thanks to that technical edge, this school may have been better placed than some others to adapt and change amid the severe challenges of the lockdown earlier this year.

Yelena Ivanova, a social studies teacher with 30 years experience, says that when the first wave of the pandemic hit earlier this year, it disrupted everything and no one had any idea what to expect.

“It was really awful, like nothing we’d ever experienced,” she says. “But we gradually discovered that we had all the tools we needed to deal with it. All these technologies were in place. We had computers. We were already customizing lessons for individual students, but it had all been in the form of routine computer lessons. When this happened, we needed to put it all together in new ways, to keep as much education going as we possibly could.”

But she has also learned that there is no substitute for direct classroom contact between teacher and pupils, she says.

“Even for older students, who know how to use the devices and study on their own, some issues can only be dealt with face-to-face,” she says. “It’s a matter of socialization, which is crucial to the learning process. We’ve discovered a lot about how technology can assist, but there will never be any replacement for personal contact.”

One of the educational scholars who advised Moscow about the experimental plan to throw pedagogical students onto the front lines for the pandemic’s duration is Yefim Rachevsky, director of the Tsaritsyno Education Center in Moscow. He says that it’s a crisis measure that should probably be considered for permanent implementation.

“Medical students have to go through years of internship, but student teachers only get brief periods of actual practice in classrooms before they graduate,” he says. “This stopgap measure has shown a way for students to integrate more thoroughly into the system, understand the job, and for employers to see if they’re up to it.”

“Why practice on my kids?”

The project has drawn fire from some teachers and parents, who see it as an inadequate solution that the authorities are taking too much credit for.

“I wonder why anyone thinks a young student can replace an experienced older teacher?” says Alexei Bykov, father of two sons, one of whom is in grade three and the other in grade six. “I understand that they need practice, but why practice on my kids? Last spring we had 2 1/2 months of so-called remote study, and the results were terrible. In fact, many families cannot afford to have their kids at home, studying by computer. I’m not in bad shape, but I can’t afford to have two computers at home. ...

“I want my children to study at school with their teachers. Even if they need to do something like two weeks on and two weeks off it would be preferable to this, which I think will only lead to chaos.”

Yelena Kosarikhina, a retired Moscow school principal, says that inexperienced students simply cannot handle the job.

“Sure, young students may know how to use the technology, but they lack vital teaching experience,” she says. “I can’t see this working. And how long is it going to go on? At first they said it would just be a month or two. Now they’re saying a year or more. The longer it continues, the more older teachers will be sidelined, and the quality of education will deteriorate.”

The pandemic has been a shock to the whole educational system, and time will tell what’s been learned through efforts to manage the crisis, says Alexander Adamsky, editor of Vesti Obrazovaniya, an online journal of education.

He praises the young students who are stepping up to help in the classrooms, calling them “something like a volunteer corps, called into service in war time.”

“But the whole conservative model of teaching, where a teacher stands in front of a class and delivers a set amount of material and assigns huge amounts of homework, has been profoundly challenged,” he says. “As a result of this emergency, our educational officials are in a state of near paralysis, parents are up in arms, and schools have been forced to seek their own solutions. ...

“A lot of problems have been exposed, but the system has also been forced to adopt some innovative new methods. Let’s wait and see whether it will all lead to a better understanding of our children’s educational needs.”