Europe's far-right parties set for big wins. Why?

Loading...

| The Hague

François Askamp is typical of Europe’s disaffected voters. The 34-year-old Dutchman isn’t at work on a recent day in his working-class neighborhood in The Hague. He just lost his job as a mover. Thanks to a stagnant economy and burst housing bubble, people are moving less, and he sees little hope for another job anytime soon.

Instead, he’s waiting for a friend, his hands stuffed into the pockets of his leather jacket, as streams of neighbors walk by. Most of them are foreigners. And there is no subtlety to the blame he places on them for changing the community into something he barely recognizes anymore: Dutch bars are now Polish, the traditional bakeries are now run by Moroccans, and Bulgarians and Romanians now increasingly call this patch of The Hague, Rustenburg, home.

It’s this sense of uncertainty about the future that has drawn him to Geert Wilders, the populist Dutch politician who rails against Islam and increasingly against Europe. Even after a serious political gaffe, Mr. Wilders still has wide appeal among a broad spectrum of the population.

“I am not racist, and I don’t think Geert Wilders is racist either,” says Mr. Askamp. “What I like is that he says Dutch people should come first.”

A quarter of voters in Rustenburg, which was once solidly working-class Dutch before foreigners arrived a decade and a half ago, voted for Wilders in the 2012 federal elections. And it is typical of neighborhoods across Europe that are showing interest as populist parties promise to return countries to older times: before the economic crisis, before immigration, before the rise of Brussels (where many European Union institutions are based).

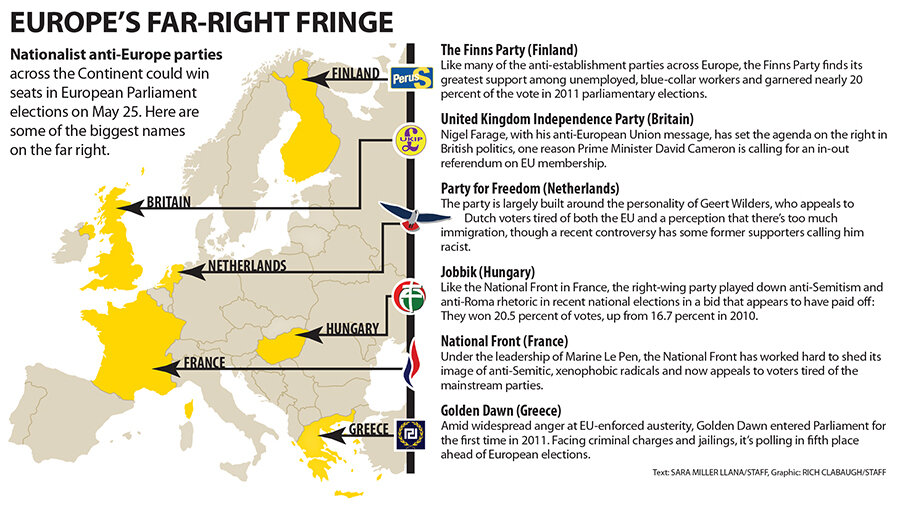

This month, Europe will elect 751 new members of the European Parliament. Populist groups like Wilders’s Party for Freedom (PVV), Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), and others from Hungary to Finland are poised to win record numbers of votes. A recent poll from Open Europe shows that anti-establishment parties could win 218 out of 751 seats (29 percent), up from 164 out of 766 (21.4 percent) in the current Parliament.

Their popularity is posing problems most immediately to the mainstream parties of Europe, but it could affect national and even European agendas on hot-button issues, such as integration of Muslims and the EU itself.

“They are tapping into this feeling people have,” says Mathieu Segers, an expert on European integration at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. “They don’t feel at home anymore in their own countries.”

Decreasing tolerance...

The Netherlands is a famously tolerant society and has looked “outward” since its golden age of seafaring in the 17th century. Today, everyone from food staff to foreign ministers speaks perfect English.

But in the past few decades, it has shown a growing populist streak. The rise of populism was first expressed politically in the Netherlands with Pim Fortuyn, the maverick politician who called for the country to close its doors to Muslims before he was assassinated in 2002 during federal elections. His killer turned out to be an animal rights activist. However, the murder of filmmaker Theo van Gogh two years later – by a Dutch-Moroccan offended that Mr. Van Gogh’s film “Submission” criticized the treatment of women in Islam – stoked anti-immigration sentiments that Wilders tapped into when he entered the political scene with his PVV 10 years ago.

Europe sat nervously ahead of Dutch 2012 federal elections, in which Wilders was slated to win big. He did not, but that was mostly because of coalition politics – specifically his role in bringing down the then-governing coalition – not because his ideas were no longer appealing.

Now the PVV and other right-wing parties look set for major gains in the European Parliament. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the right-leaning Liberals in the Netherlands is trailing Wilders in polls leading into the Netherlands’ European elections. In France, Socialist President François Hollande is the most unpopular leader of the Fifth Republic. That opens the door for Ms. Le Pen, whose National Front won a record 11 towns in March municipal elections, to vie with the conservative right for the most French members of the European Parliament.

Europe’s mainstream has sought to write off Wilders, Le Pen, and other like-minded politicians as fascist racists, not unlike the leaders who took over the political space in 1930s Europe. “We should not forget,” said José Manuel Barroso, head of the European Commission, this fall “that in Europe, not so many decades ago, we had very, very worrying developments of xenophobia and racism and intolerance.”

...and increasing fiscal woes

But their popularity today stems from far more than intolerance. A new anger is directed at Brussels as the EU faces an image crisis unparalleled since its inception. In a Pew Global Attitudes Project last May, those with a favorable view of the EU fell from a median of 60 percent in 2012 to 45 percent in 2013. And part of Wilders’s revival since the 2012 elections comes from his shift of emphasis away from immigration, says Andy Langenkamp, a political analyst with ECR Research in the Netherlands. “Wilders had to find another subject on which to score points, and EU- and euro-bashing has proved successful,” he says.

The Dutch were founding members of nearly all the postwar alliances, including the EU. And with fiscal prudence and an open, liberal economy, they have aligned in the eurocrisis with the generally more frugal economies of northern Europe. In the 2013 Transatlantic Trends survey of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, their support for the EU sat at the median.

But as Europe’s troubles pushed the public deficit into the red, prompting continuous austerity cuts, the growing public distrust has become apparent. While 75 percent of the Dutch said in 2010 that the EU had been good for their economy, that dropped to 60 percent by 2013. Many of them resent having to pay for the “mistakes” of southern Europe and an EU that they say meddles in their lives.

Many in the Netherlands understand the EU as a force for positive change, says Jan Braakman, a journalist covering the agricultural industry. He notes that farmers, for example, don’t tend to vote for Wilders because EU agricultural subsidies have helped them. “But,” he adds, “many people increasingly can’t see what Europe does for them.”

The Hague is not only the seat of the federal government, but is one of Europe’s most “international” cities, with the International Court of Justice housed in the 100-year-old Peace Palace. Yet at the local level, it was only one of two municipalities where the PVV has fielded candidates – and won. The local PVV office directs journalists to the national party; it declined requests for an interview.

Many complaints, few solutions

In a cafe on the ground floor of The Hague’s sun-filled city hall, Ibo Gulsen, outgoing city councilor with the Liberals, attributes the PVV’s success to the anti-establishment vote that always exists. Even though they won seven seats in March local elections, he’s not concerned about their effect on the politics of the city (though a coalition is still under negotiation). “They don’t bring any value to the table. They only say what they don’t want,” he says.

Back in Askamp’s neighborhood, Victor Meijer, the local poultry shop owner – as well as The Hague’s city poet – largely agrees, as locals pour in for breaded cutlets. His store resembles a coffee house more than a poultry joint, with a stuffed pheasant and a slew of poetry books decorating the food counter.

Tall, with silver hair and blue eyes, Mr. Meijer ran for city councilor this year with the party Groep de Mos, though he did not get a seat. While he condemns Wilders for his radical opinions on Islam, he sees how the Euroskeptic card appeals to many Dutch people today. Holland doles out money to Europe “like Santa Claus,” he says. “And we have food banks here.”

For Paul Nieuwenburg of Leiden University in the Netherlands, this sentiment is a typical response to the deepening integration of Europe, not unlike the reaction to globalization for many people: It makes them embrace the local. “I think there is an increasing rift between political and intellectual [spheres] that are pro-Europe and what goes on in other parts of society,” he says.

The populist parties of Europe have tried to capitalize on the mood. Wilders and Le Pen announced a parliamentary alliance of Euroskeptics aimed at undoing the hegemony of Brussels from within. Le Pen, speaking at a meeting in January with foreign correspondents from the Anglo-American Press Association of Paris at her party headquarters in Nanterre, referred to the European “Soviet” Union. “How to improve the European Union? By precipitating its collapse. We knocked down the Berlin Wall; we have to knock down the wall of Brussels,” she says.

There are many reasons to dismiss this alliance as nothing more than savvy politics. While Le Pen and Wilders have announced their cooperation, they have failed thus far to draw other fringe movements to their alliance, notably UKIP in Britain. And they have incompatible ideas in the first place. While Wilders is pro-Israel – though his support among Jews and many others has waned after a miscalculated “anti-Moroccan” chant at a political rally this winter – the National Front’s reputation has suffered from its anti-Semitic roots. UKIP hasn’t wanted to associate with the racist overtones of either party.

And while these parties have no reticence about declaring what they don’t like, they have offered few alternatives about their vision for a post-union Europe – the same criticism heard at the local level.

A destructive influence?

Even if they win at the European level – which is more prone to a “protest” vote than national elections – that does not necessarily translate into national power. In fact, Cas Mudde, an international affairs professor at the University of Georgia in the US, has pointed out that despite stunning gains made by Golden Dawn in the 2012 Greek elections, or the surprise 20 percent that the National Front garnered in France’s 2012 elections, in only 19 of 28 EU states has the far right won more than 1 percent of the vote in national elections between 2005 and 2013.

But analysts say the movement cannot and should not be dismissed outright. For Mr. Segers, Wilders might appeal to voters’ gut feelings, but in reality the country remains a member of the eurozone. “If [the country] wants to move forward, see new opportunities, catch up with growth, reform society so that it’s fitter for the future, it’s probably a good idea to be constructive in the European debate,” he says. “But the Dutch government and public is unable to think constructively about European integration, placing itself outside the main decision making within the eurozone.”

The rise of populism in Europe could also lead to its own version of a US “shutdown” at a time when the EU tries to navigate out of crisis and aspires to have a credible say in world affairs. If populist parties win 25 seats or more in at least seven member states, their sway will be undeniable, says Mr. Langenkamp. “The bloc will have enough clout to obstruct the European decisionmaking process from within.”