Is the Islamopocalypse really upon us?

Loading...

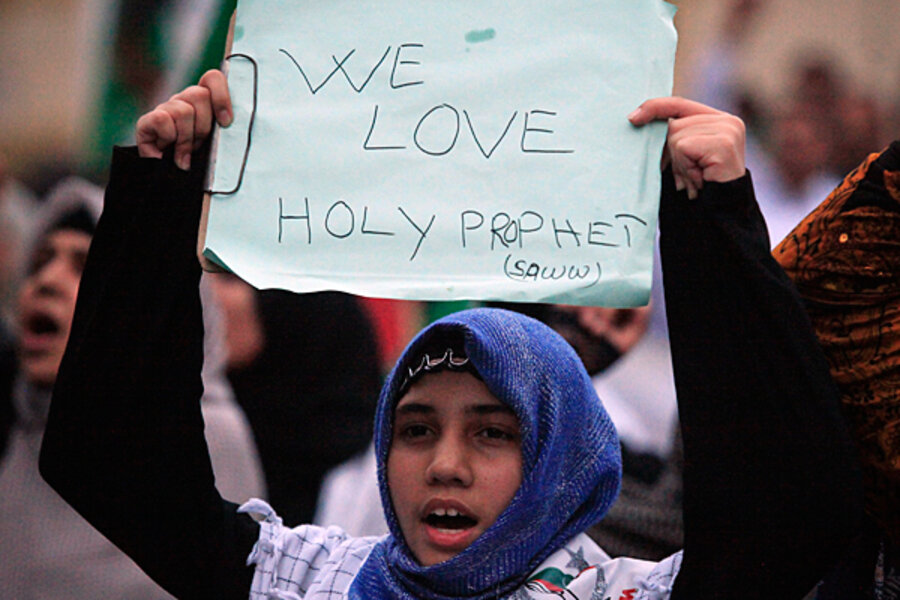

You are forgiven if you hold the mistaken belief that the entire Muslim world is aflame with anti-American "rage." Cable news has been pumping the message for days now, and Newsweek has jumped on the bandwagon with a cover that perfects the approach to the world's 1.5 billion Muslims as a violent, reactive mob.

"Muslim Rage," screams the banner headline for an article written by anti-Islam activist Ayaan Hirsan Ali, over a picture of two men (one helpfully wearing a turban) looking rageful. "How I survived it, How we can end it," goes the subhead.

I'll return later to the policy dangers of viewing the world's Muslim inhabitants as an undifferentiated mass that can be "solved."

But it's time for some perspective. The protests in more than 20 Muslim countries, over a deliberately insulting YouTube video, have been small. Small as a proportion of the world's Muslims, and small when compared to other Muslim "insult" protests in the past. And almost certainly small, when their impact is considered a few months from now.

As the #muslimrage Twitter hashtag (killing Newsweek with comedy) has pointed out all day, most Muslims aren't raging at the US or anything else. Some are raging at rude taxi drivers. Others are kind of nervous about problems at work. And still others are thinking about maybe having a sandwich.

While sensational headlines have played up the story, the cumulative total of protesters so far in about 30 countries appears well under 100,000. At Tahrir Square on Friday, wide angle overhead shots (rather than the tight, ground shots favored by TV news producers) showed a sparse group reminiscent of Mubarak-era political protests (when people ran a major risk of going to jail for simply shouting slogans) and not the hundreds of thousands that have routinely come out to protest against their own government in the past year-and-a-half.

And if you expect the occasional mass freakout like this, as I do, there's actually a small sign of progress in these protests. The protests over the Danish cartoons mocking the prophet Muhammad in 2006 were larger and more violent, and there was far less in the way of condemnations of the violence and apologies from Muslim-majority states than there have been this go around.

Ashraf Khalil, whose judgment I trust, estimated about 1,000 protesters at Tahrir on Friday, with a further 300 football hooligans picking a fight with riot police nearby. That's in a city of 15 million people, at least 90 percent of them Muslim. In Jakarta, Indonesia, a few hundred protesters clashed with police (who outnumbered them by 3 or 4 to 1) near the US embassy. Jakarta is, like Cairo, another sprawling Muslim majority city.

I've seen big protests in both – the popular uprising that ended the US-backed dictator Soeharto's reign in 1998, and the popular uprising that ended the US-backed dictator Hosni Mubarak's reign in 2011 – and by those standards these were not protests at all.

This doesn't mean that there's no story here or events aren't worth paying attention to. It's just that there's nothing new to learn about the "Muslim world" in all this. Yes, it's true that many Muslims are intolerant of perceived insults against their religion. Yes, a lot of Muslims don't much like the US. If you think that's news, try getting out more.

What we can learn is about the specifics of each country, from both how events unfolded and how government's responded. Consider Libya, where Ambassador Chris Stevens and three of his colleagues were murdered in the second-largest city, Benghazi. It was a terrible tragedy that says something about post-Qaddafi Libya, but little about anywhere else. The Americans were killed by one of the dozens of militias that continue to roam the country, particularly in Benghazi. The particular militia is almost certainly one of the anti-American jihadi outfits operating there.

Is there good news in that? Of course not. But the Libyan authorities have vigorously pursued the culprits and pro-American demonstrations have been held in both Benghazi and Tripoli.

In Egypt, we learned something about new President Mohamed Morsi, who was propelled to the presidency earlier this year by the Muslim Brotherhood. Security was nonexistent when a crowd of maybe 2,000 protesters descended on the US embassy and managed to scale the wall and destroy the US flag flying there. Most of the protesters breaching the embassy walls, and the violent group at Friday's protest, were football hooligans, mostly out for a fight with the cops, not Islamist ideologues.

Still, in the first day after that incident, Mr. Morsi was largely silent on the embassy breach, and far more interested in complaining about the insult to Islam. But he changed his tune after furious private complaints from the US and a pointed comment made by President Obama that Egypt is not a US "ally." Is the fact that the democratically elected president of Egypt isn't a particular fan of free speech or of the US positive? Of course not. But does the fact that he changed his tune and eventually did the right thing (security was much better for Friday's protest) tell us that a way to work with the new Egyptian government can still be found? Of course.

Then there's Lebanon, where Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah emerged to join some of the most raucous anti-American protests in the world. Though Mr. Nasrallah's America-hating credentials hardly need any burnishing, his regional popularity has been on the wane, since he's seen as a close ally of President Bashar al-Assad in neighboring Syria, where the civil war has claimed at least 30,000 lives so far. The hypocrisy of protesting a 14-minute YouTube clip while staying silent about a Syrian leader who's had thousands killed was noted by many.