Reported death of Uzbek president launches succession speculation

Loading...

| ALMATY, KAZAKHSTAN

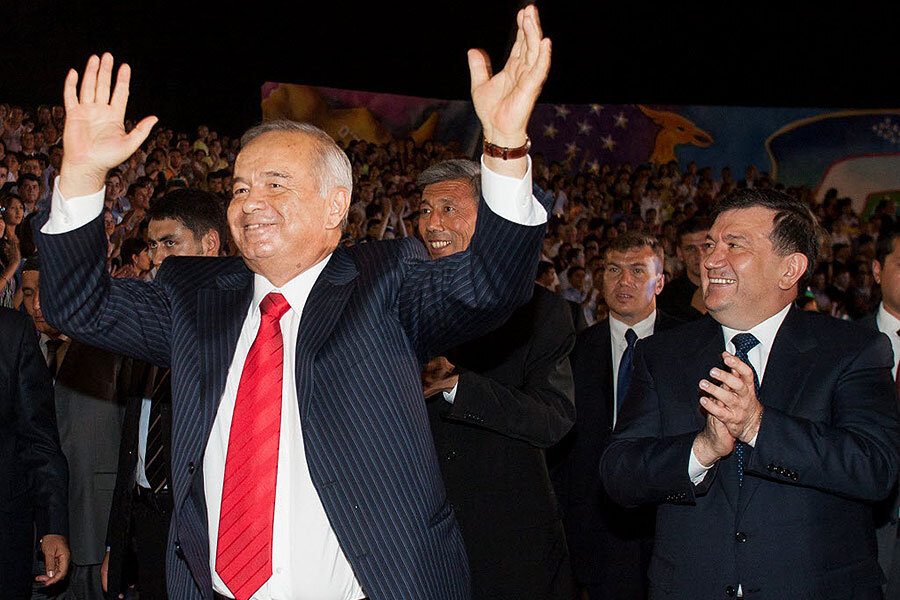

Uzbek President Islam Karimov has died, three diplomatic sources told Reuters on Friday, leaving no obvious successor to take over the Central Asian nation of 32 million people.

The Uzbek government did not immediately confirm the reports. Earlier on Friday it said the health of Karimov, who has been in hospital since last Saturday, had sharply deteriorated.

Long criticized by the West and human rights groups for his authoritarian style of leadership, Karimov had ruled Uzbekistan since 1989, first as the head of the local Communist Party and then as president of the newly independent republic from 1991.

"Yes, he has died," one of the diplomatic sources said when asked about Karimov's condition.

Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim became the first foreign leader to offer condolences over the death of Karimov, whose former Soviet republic has close ethnic, cultural and linguistic ties with Turkey.

Karimov did not designate a successor and analysts say the transition of power is likely to be decided behind closed doors by a small group of senior officials and family members.

If they fail to agree on a compromise, however, open confrontation could destabilize Uzbekistan, which shares a border with Afghanistan and has become a target for Islamist militants.

"The murky nature of Uzbek politics, combined with Islamist groups trying to destabilize the regime, means that the moment is fraught with uncertainty," The Christian Science Monitor's Fred Weir reported on Monday:

Uzbekistan is a poor country, with a closed economy, but it is rich in resources and has enjoyed annual growth rates of more than 7 percent for several years. But poverty and unemployment are serious problems, particularly in the teeming, multi-ethnic Ferghana Valley, which has seen repeated explosions of Islamist-inspired violence. Most serious was a mass insurrection in the Ferghana city of Andijon 11 years ago, put down with exceptional ferocity by Karimov's security forces.

"There is a danger that inner-circle strife could trigger social unrest," says Alexei Makarkin, deputy director of the independent Center of Political Technologies in Moscow. "Islamist influences do exist in Uzbekistan, even if they have been driven underground."

The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a sometime ally of the Taliban and Al Qaeda, would move swiftly to exploit any instability, says [Vladimir Sotnikov, director of the independent Russia-East-West Center for Strategic Analysis in Moscow]. Though the group's leaders are living in exile in Pakistan, it maintains considerable strength among the ethnic Uzbek population of northern Afghanistan, and could be capable of launching raids inside Uzbekistan as it did in the past.

Succession

A hint at who will succeed Karimov may come with the government's announcement of his death – which one source said was expected later on Friday – and whoever it names to head the commission in charge of organizing the funeral.

The funeral appeared likely to take place in Karimov's hometown of Samarkand, where his mother and two brothers are also buried. Municipal authorities there mobilized public workers to clean the central streets late on Thursday.

A source in the government of neighboring Kazakhstan told Reuters on Friday that Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev planned to cut short his visit to China and travel to Uzbekistanon Saturday, although Nazarbayev's office later denied that.

Among potential successors to Karimov are Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev and his deputy Rustam Azimov. Security service chief Rustam Inoyatov and Karimov's younger daughter Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva could become kingmakers.

According to the constitution, Nigmatilla Yuldoshev, the chairman of the upper house of parliament, is supposed to take over after Karimov's death, and elections must take place within three months.

However, analysts do not consider Yuldoshev a serious player. His erstwhile counterpart in Turkmenistan, who was also supposed to become interim leader after the death of authoritarian president Saparmurat Niyazov in 2006, was quickly detained and thus eliminated from the line of succession.

Whoever succeeds Karimov will need to balance carefully between the West, Russia and China, which all vie for influence in the resource-rich Central Asian region.

Another task of the new leader will be resolving tensions with ex-Soviet neighbors Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan over borders and the use of common resources such as water.

Reporting by Olzhas Auyezov in Almaty and Lidia Kelly in Moscow; Editing by Christian Lowe and Gareth Jones