Myanmar vote: Suu Kyi says she'll hold the true power if her party wins

Loading...

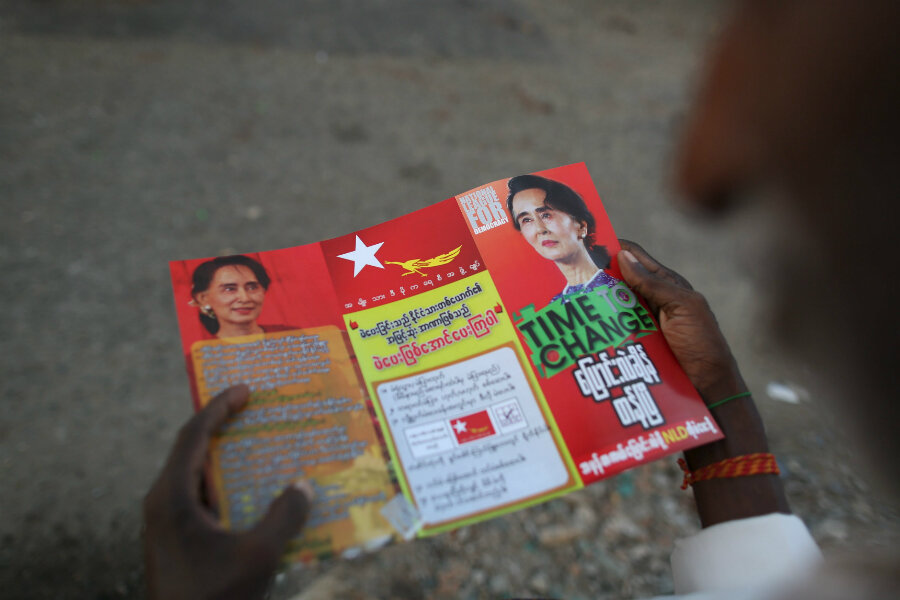

Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s best-known voice for political reform, today pushed hard against her country's military rulers ahead of historic elections Nov. 8, challenging them to hold a free and fair vote and saying that a victory for her party would give her a position “above the president.”

Sunday’s polls will be the first real democratic vote in the Southeast Asian nation in nearly a quarter century. The vote is widely viewed as a contest between authoritarian forces and those of civil society and political freedoms that Aung San Suu Kyi has championed.

A constitutional ban was specifically created in 2008 to block her from holding Myanmar’s top job. But Aung San Suu Kyi told reporters today that she would sit above the president, avoiding any violation of the Constitution.

“It's a very simple message,” she said, according to the Associated Press, which reported that "while another member of her National League for Democracy party would hold the presidential title, 'I'll make all the proper and important decisions.' "

Her message, delivered at a press conference at her lakeside home where she was held under arrest for nearly 15 years, elaborated on previous assurances by the Nobel laureate that a vote for her National League for Democracy party is a vote for her leadership.

Yet the head-on challenge “could complicate her already fraught relations with Myanmar's military,” according to Reuters. Aung San Suu Kyi’s statement was “rebutted by Zaw Htay, a senior official at the President's Office,” who told the news agency that her comments were "against the constitutional provision."

In 2011, a political thaw led to the opening of Myanmar to foreign investment and a quasi-civilian government after more than 50 years of military rule. In the Nov. 8 election, 25 percent of the seats in parliament are reserved for parties connected to the military and 75 percent are open.

The Wall Street Journal today focused on growing fears that the elections will be tampered with, and Aung San Suu Kyi’s statements concerning this, writing that she:

struck a defiant stance ahead of Sunday’s election and hinted that her party would deem the result illegitimate if it doesn't clinch a decisive majority, setting up a showdown with Myanmar’s still-powerful military.

If the result “is too suspicious, we will have to make a fuss about it,” Ms. Suu Kyi said Thursday at her first news conference in a year following three months of campaigning around the country with thousands turning out at her rallies. The defiant tone shows Ms. Suu Kyi expects a big win for her party.

Aung San Suu Kyi, whose assassinated father is considered a national hero, has long been the most inspiring leader in the nation, sometimes considered a mother figure. She emerged in 1988 out of an uprising against the military junta, and the party that emerged out of that movement won a landslide victory in elections that were quickly nullified by the junta.

In 2008 the junta, fearful that a political opening would lead to her taking control, passed a constitutional provision that individuals whose family members have foreign affiliations cannot be president. Aung San Suu Kyi's late husband was a British scholar, and they had two children. Yet today she defied the parameters of the ban, according to The Wall Street Journal:

“Constitutions are made by people, and they are not eternal. If the support of the people is clear and strong enough, I don’t see why we should not be able to overcome minor problems like amendments of the constitution,” she said of the document.

Today, Gen. Shwe Mann, one of the nation's most influential politicians and a former junta leader who was ousted this summer, described Aung San Suu Kyi's party, the NLD, as the most popular in the country in an interview with Reuters, and said he would work with her if the NLD took power. [Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Shwe Mann's previous position.]

Shwe Mann leads a sizeable parliamentary faction of the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). If Suu Kyi fails to win a majority, support from one of the former top generals in the junta could help her form a government.

Shwe Mann has said little in public about his close ties to Suu Kyi, which aroused the suspicion of some USDP members and contributed to his dramatic sacking, the biggest shake up of Myanmar's political establishment since the end of military rule in 2011. The two have met frequently and found much common ground, Shwe Mann told Reuters late on Wednesday in a rare interview with international media.