China's passport propaganda baffles experts

Loading...

| Beijing

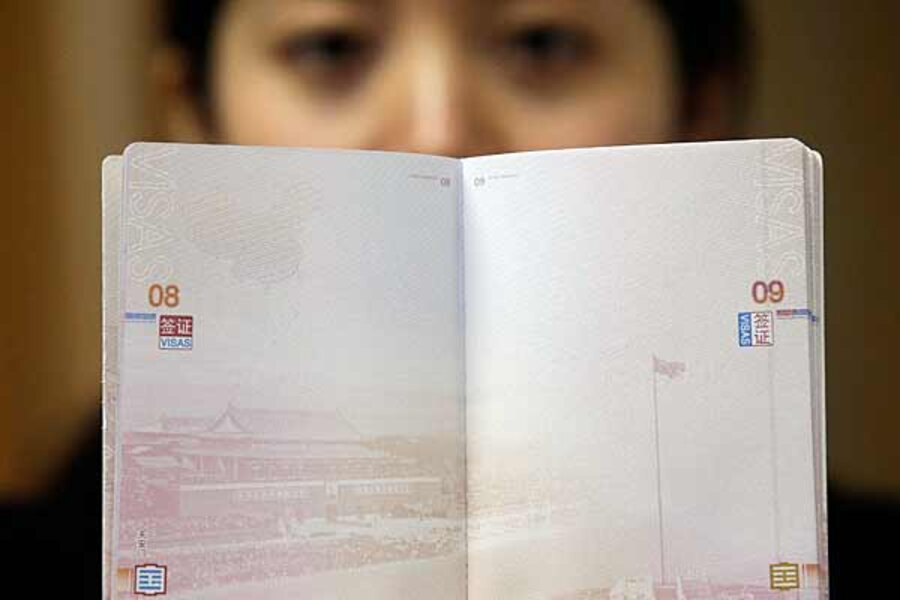

China’s neighbors are seething with anger over new Beijing-issued passports that they see as the latest, underhand, Chinese jab in an ongoing regional row about maritime territory.

Beijing has infuriated India, too, with its e-passports, decorated with a map of China that shows disputed territories across the South China Sea – and Himalayan land that New Delhi claims – as belonging to China.

Vietnam is refusing to stamp the new passports with visas, for fear that to do so would imply acceptance of China’s claims. The Indian consulate in Beijing is stamping its own map of the disputed border when it affixes visas to the new passports.

The quiet Chinese move has baffled even some Chinese experts.

“I do not know why they decided to do this,” says Niu Jun, professor of international relations at Peking University. “It cannot resolve any of the disputes with our neighbors and we could expect a response from the other countries.”

At Vietnam’s border with China, Vietnamese officials are not pasting visas into the new passports, but issuing them on separate pieces of paper.

The Vietnamese government says it has sent a diplomatic note to Beijing asking the Chinese government to remove “erroneous content” from the new passports.

The Chinese government began issuing the passports, which contain an electronic chip with the holder’s personal data, last April. It is believed to have handed out more than 5 million of them, but the map began stirring controversy only a few days ago.

The Philippines, engaged in a fierce territorial dispute with China over fishing grounds near the Scarborough Shoal, has protested to Beijing. Taiwan, which Beijing claims as an integral part of its territory but which enjoys de facto independence, has also complained.

“This is total ignorance of reality and only provokes disputes,” said Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council, the body responsible for relations with China, in a statement last week.

The map of China, on page 8 of the new passports, shows a dotted line to illustrate China’s territorial claim to almost the whole of the South China Sea, which puts it in conflict with a number of its neighbors, such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei.

Washington has dismissed the map as irrelevant.

“Stray maps that they include are not part” of international standards that passports must meet, US State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland said Monday.

“These issues need to be negotiated among the stakeholders, among ASEAN and China, and, you know, a picture on a passport does not change that,” she added.

China has defended its new travel documents as being in line with international standards.

“China is not targeting a specific country,” Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said on Friday. “China is willing to communicate with relevant countries and continue to promote contacts.”

The passport row is the latest flare-up of tensions in the South China Sea that are complicating Beijing’s relations with several of its neighbors.

In May, China suspended the import of bananas from the Philippines until Manila backed down in a dispute over fisheries around the Scarborough Shoal.

In June, the state owned Chinese oil company CNOOC invited foreign firms to bid for exploration rights in an area close to Vietnam’s coast. A month later Beijing announced that it was upgrading the town of Sansha, in the Paracel Islands, which it seized from Vietnam in 1974, to the status of a prefecture-level municipality and would soon station troops there.

China is also embroiled in a territorial dispute with Japan over three uninhabited islands in the East China Sea known in Chinese as the Diaoyu islands and in Japan as the Senkaku. Both sides have sent surveillance and coast guard vessels to patrol the disputed waters, raising fears of a clash.