After two years, Ethiopia and Tigray make tentative peace

Loading...

| Pretoria, South Africa

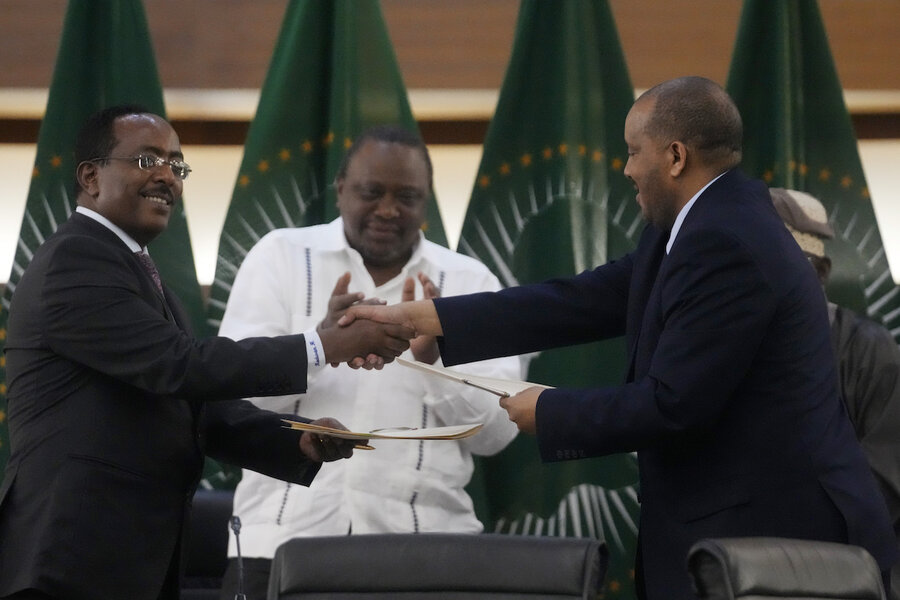

Ethiopia’s warring sides agreed Wednesday to a permanent cessation of hostilities in a 2-year conflict whose victims could be counted in the hundreds of thousands, but enormous challenges lie ahead, including getting all parties to lay down arms or withdraw.

African Union envoy Olusegun Obasanjo, in the first briefing on the peace talks in South Africa, said Ethiopia’s government and Tigray authorities agreed on “orderly, smooth and coordinated disarmament.” Other key points included restoration of services to the long cut-off Tigray region and “unhindered access to humanitarian supplies.”

The war in Africa’s second-most populous country, which marks two years on Friday, has seen abuses documented on either side, with millions of people displaced.

“The level of destruction is immense,” the lead negotiator for Ethiopia’s government, Redwan Hussein, said. Lead Tigray negotiator Getachew Reda expressed a similar sentiment and noted that “painful concessions” had been made. Exhausted Ethiopians then watched them shake hands.

The full text of the agreement, including details on the disarmament and reintegration of Tigray forces, was not immediately available. “The devil will be in the implementation,” said former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, who helped facilitate the talks.

Major questions remain. Eritrea, which has fought alongside neighboring Ethiopia, was notably not part of the peace talks. It’s not immediately clear to what extent its deeply repressive government, which has long considered Tigray authorities a threat, will respect the agreement. Eritrea’s information minister didn’t reply to questions.

Eritrean forces have been blamed for some of the conflict’s worst abuses, including gang-rapes, and witnesses have described killings and lootings by Eritrean forces even during the peace talks. On Wednesday, a humanitarian source said several women in the town of Adwa reported being raped by Eritrean soldiers, and some were badly wounded. The source, like many on the situation inside Tigray, spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Forces from Ethiopia’s neighboring Amhara region also have been fighting Tigray ones, but Amhara representatives are not part of the peace talks. “Amharas cannot be expected to abide by any outcome of a negotiations process from which they think they are excluded,” said Tewodrose Tirfe, chairman of the Amhara Association of America.

Another critical question is how soon aid can return to Tigray, whose communications and transport links have been largely severed since the conflict began. Doctors have described running out of basic medicines like vaccines, insulin, and therapeutic food while people die of easily preventable diseases and starvation. United Nations human rights investigators have said the Ethiopian government was using “starvation of civilians” as a weapon of war.

“We’re back to 18th century surgery,” a surgeon at the region’s flagship hospital, Fasika Amdeslasie, told health experts at an online event Wednesday. “It’s like an open-air prison.”

A humanitarian source said their organization could resume operations almost immediately if unfettered aid access to Tigray is granted. “It entirely depends on what the government agrees to ... If they genuinely give us access, we can start moving very quickly, in hours, not weeks,” said the source, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

The conflict began in November 2020, less than a year after Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for making peace with Eritrea, which borders the Tigray region. Mr. Abiy’s government has since declared the Tigray authorities, who ruled Ethiopia for nearly three decades before Mr. Abiy took office, a terrorist organization.

The brutal fighting, which also spilled into the neighboring Amhara and Afar regions as Tigray forces tried to press toward the capital, was renewed in August in Tigray after months of lull that allowed thousands of trucks of aid into the region. According to minutes of a Tigray Emergency Coordination Center meeting on Oct. 21, seen by the AP, health workers reported 101 civilians killed by drone strikes and airstrikes, and 265 injured, between Sept. 27 and Oct. 10 alone.

In a speech Wednesday before the peace talks’ announcement, Ethiopia’s prime minister said that “we need to replicate the victory we got on the battlefield in peace efforts, too. We are finalizing the war in northern Ethiopia with a victory ... we will now bring peace and development.”

This story was reported by The Associated Press. Cara Anna reported from Nairobi, Kenya.