It’s a United Nations-backed certification program meant to ensure that none of the world’s diamonds are so-called “blood diamonds” – that is to say, stones mined by rebel groups and used to fund armed resistance movements.

The program came about in the early 2000s amid rising international awareness that rebel groups in Angola, Sierra Leone, and the Congo were mining diamonds under horrific conditions and then using the profits to wage bloody wars against their governments.

At the time, the global diamond supply chain was frustratingly opaque. Required only to carry a certificate from the last country they were exported from, many diamonds smuggled from conflict zones quickly disappeared into the international market, their origins unknown. As a Monitor report described the situation at the time:

The journey of an African diamond to a newlywed's finger is a long and often tortuous one. From high-security mines in peaceful Botswana or muddy pits in Congo, the rough, dull stones travel in pockets or planes through jungles and over deserts, eventually landing in cutting and polishing centers in New York, Antwerp, and Tel Aviv. Often, they pass through the hands of several middlemen in different countries, making it difficult to track their original origin.

When they reach glass display cases in the US - which makes up more than half of global diamond jewelry retail sales - they all sparkle. It is impossible to tell which are stained with the blood of African civil wars.

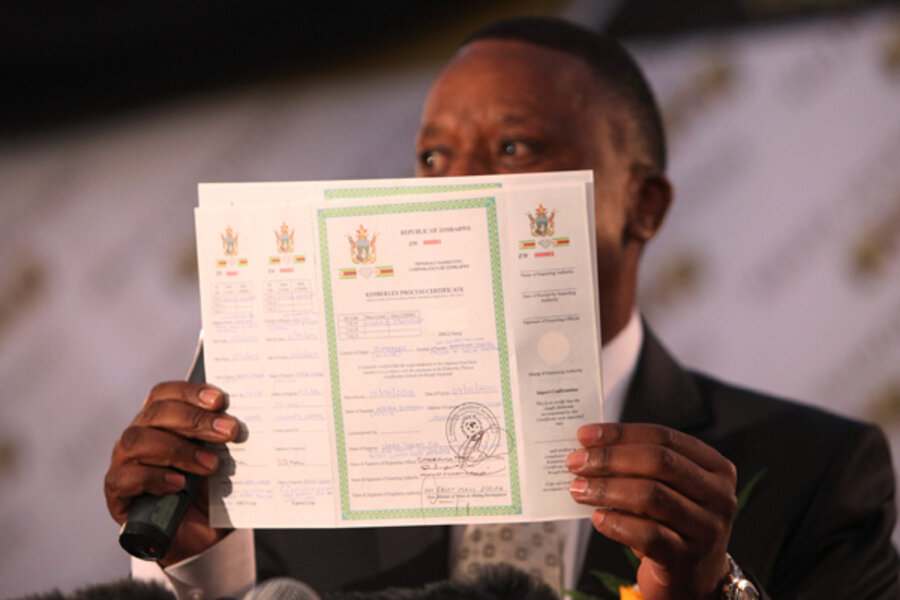

In 2003, dozens of nations signed on to an agreement officially known as the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, which required that all diamonds bound for international markets be certified as conflict free.